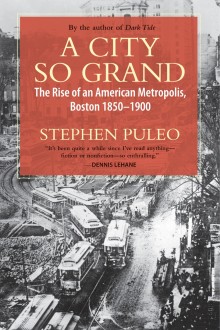

A City So Grand

The Rise of an American Metropolis, Boston 1850-1900

The second half of the nineteenth century is, quite simply, a breathtaking period in Boston’s history. Unlike the frustrations of our modern era, in which the notion of accomplishing great things often appears overwhelming or even impossible, Boston distinguished itself between 1850 and 1900 by proving it could tackle and overcome the most arduous of challenges and obstacles with repeated, and often resounding, success.

A City So Grand chronicles this breathtaking period in Boston’s history for the first time. Readers will experience the abolitionist movement of the 1850s, the 35-year engineering and city-planning feat of the Back Bay project, the arrival of the Irish that transformed Boston demographically, the Great Fire of 1872 and the subsequent rebuilding of downtown, Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone in Boston, and the many contributions Boston made to shaping transportation, including the Great Railroad Jubilee of 1851 and the grand opening of America’s first subway.

These stories and many more paint an extraordinary portrait of a half-century of progress, leadership, and influence that redefined Boston as a world-class city.

Reviews

Dennis Lehane, Author

“A City So Grand is a book so grand. It’s been quite a while since I’ve read anything — fiction or non-fiction — so enthralling. My only complaint is that it ended.”

The New England Quarterly

Wilfred E. Holton – March 2011

Stephen Puleo, a historian and journalist, sets out to chronicle the half-century-long period of “Boston’s metamorphosis from a large and insulated town to a thriving metropolis that achieved national and international prominence in politics, medicine, education, science, social activism, literature, commerce, and transportation.” He does this in an effective but unusual way, zeroing in on specific incidents in Boston while providing a wealth of information on related national events.

Puleo narrates the abolitionist movement and the Civil War in relation to Boston, the early women’s suffrage movement, and the massive influx of Irish immigrants into the city, where they faced harsh treatment. Other sections of the book focus on changes brought about by transportation innovations like steam railroads, electric streetcars, and the nation’s first subway. Puleo details the new technologies and diverse motivations that led to the massive Back Bay landfill project, touches on the annexation of independent cities and towns as part of metropolitan expansion during this period, and covers the effects of the Great Fire of 1872 and other important events in the later nineteenth century.

Puleo crafts compelling stories to introduce his themes and make his points. For example, the section on abolitionism begins with the gripping tale of radical antislavery activists’ failed attempt to free runaway slave Thomas Sims from jail on Fugitive Slave Law charges in 1851. A description of the furor surrounding the 1851 appointment of Barney McGinniskin as the first Irish-born Boston police officer introduces the chapter on Irish immigrants. Puleo opens his coverage of Boston and the Civil War by relating the saga of the Massachusetts Sixth Regiment, which was attacked by a Baltimore street mob in April 1861 as it rushed southward to become the first Union regiment to defend Washington. Later in the book, Puleo tells the captivating tale of Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone.

While the chapters are roughly chronological, Puleo includes contextual material at many points. Often he describes the activities of Bostonians on the national scene, adding more depth to the stories. Puleo also pays more attention to Boston’s immigrant groups and working-class interests than to the ruling elites. While high cultural and educational institutions are addressed, they are not emphasized. Overall, Puleo’s book is thorough in its coverage of the period, and readers will likely encounter much new information.

Puleo draws from a wide range of sources for his material, including several recently published books. He does utilize original sources in some instances. Although he employs no footnotes, Puleo provides a good bibliographic essay that discusses the sources he consulted for each chapter.

Stephen Puleo is an excellent writer when he is telling a story. Many riveting episodes are included throughout the book, bringing individuals and events to life for readers. The dramatic narrative about the Minkins case, for instance, clearly portrays the strains among abolitionists over breaking an unjust law. The flow of the overall story falters at some points due to the complexity of the period and the lack of gripping anecdotes.

On some topics, Puleo explores complicated issues adeptly. For example, he portrays the changing and conflicting views of Boston’s Irish-American citizens as their Civil War regiments fought bravely but suffered severe losses. Puleo relates this issue to political matters; many Irish leaders felt that Republicans did not appreciate their soldiers’ sacrifices to the Union cause.

Some sections seem less relevant to the larger history; many of these are intended as bridging elements between chapters. For in- stance, early in the chapter “Filling the Back Bay,” Puleo describes the 1851 introduction of the nation’s first electric fire alarm system in Boston, stating that this accomplishment, among others, made the ambitious landfill project seem possible. Then, still before beginning the story of the Back Bay Project, he includes a page on the founding of the Boston Public Library.

As is probably inevitable when a book covers so much material, there are some minor inaccuracies. In “Filling the Back Bay,” for example, Puleo writes that the 1821 dams in the Back Bay “provided water power for the company’s mills in Watertown, Dorchester Lower Mills, and the Neponset River” (p. 86). Thankfully, such mistakes are not critical because Puleo provides his sources, which can be checked by readers. In addition, some important topics of the period have been overlooked, such as the political transformations that occurred when Irish-Americans replaced English Protestants as the largest population group.

A City So Grand will appeal to a broad range of readers who want to understand Boston’s history during the crucial second half of the nineteenth century. The author contextualizes numerous complex elements in an eminently readable way.

Edward Glaeser – November, 2010

“Puleo rightly revels in Boston’s creativity and contradictions. He proudly, and correctly, points to the city’s accomplishments,” says The New Republic‘s Edward Glaeser in a review of Steve’s fourth book, A City So Grand. “Puleo presents us with an enjoyable catalog of wonders produced by Boston during the period under review.” Read the complete review here: The Urban Miracle.

Excerpts

Saturday, April 12, 1851

In the early morning dampness, Boston police and federal troops mustered by the weak light of a single gas lamp. It was just after 3:00 a.m., and some members of the Vigilance Committee had been meeting all night in Garrison’s office, expecting the worst and watching for evidence that today would be among the darkest in Boston’s storied history. “The dreaded moment was at hand,” historian Leonard Levy wrote. “The authorities meant to sneak Sims back into slavery while the city slept. It was not the bravest way to uphold the constitution, but it was the safest.”

More than one hundred police officers, armed with double-edged Roman swords that Marshal Tukey had borrowed from the U.S. Naval Yard in Charlestown, plus another hundred volunteers armed with clubs and hooks, drilled for more than an hour, their heavy boots clomping upon the dirt-packed street. The police officers manned the inner rectangle of the “hollow square” formation and the volunteers formed the outer square. Members of the Vigilance Committee spread the word that Sims’s departure was imminent, and by 4:00 a.m., between 150 and 200 horrified abolitionists looked on as the drilling continued.

At about 4:15, “after the moon had gone down, in the darkest hour before daybreak,” the officers and volunteers assembled in a double-filed hollow square formation, and marched to the east door of the courthouse. There, they were joined by one hundred more armed officers from the City Watch, which formed another double file around the hollow square. Then, the main doors of the Courthouse opened and Thomas Sims appeared. “Tears were streaming down his face, but he held his small dark frame erect,” Levy described. Sims was escorted into the center of the square of armed men. At Tukey’s command of “March!” the three hundred guards “began a slow regular tramp” toward the dock.

Abolitionists and Vigilance Committee members preceded them, followed them, and flanked them as the square of armed guards continued its relentless march down State Street, a despondent Sims at its center. “His sable cheeks were bathed in tears, and although he evinced the greatest grief and sorrow, he marched with a firm and manly step, like a martyr and a hero to his fate,” reported the abolitionist newspaperCommonwealth. The anti-slavery men hissed and shouted “Shame!” and “Infamy!” but one witness noted that “no other attempt at disorder was made.”

The entire mass finally arrived at Long Wharf, near the site of the Boston Tea Party, where once colonists disguised as Indians had dumped tea into the harbor to protest oppression – the irony of which was also not lost on the abolitionists. The brig Acorn, its sails unfurled, was ready for sea. The vessel was owned by John H. Pearson, whom abolitionist Wendell Phillips would one day castigate in a stinging speech, promising that abolitionists would never forget “the infamous uses he made of the Acorn. We will put the fact that he owned the brig so blackly on record…that his children – yes, his children – will, twenty years hence, gladly forego all the wealth he will leave them to blot it out.” Phillips added: “The time shall come when it will be thought the unkindest thing in the world for anyone to remind the son of that man that his father’s name was John H. Pearson and that he owned the Acorn.”

Now, though, the ship stood in the glimmer of dawn just breaking across Boston Harbor, prepared to transport its human cargo to Georgia. The hollow square of armed police marched close to the vessel, and one section broke ranks momentarily, like a door opening, to deliver its prisoner to a contingent of guards awaiting Sims on board. As Sims reached the Acorn’s deck, a man standing on the wharf cried out, “Sims! Preach liberty to the slaves!” With the last words he uttered in Boston, Sims answered with a sharp rebuke to his captors: “And is this Massachusetts liberty?” He was ushered below immediately, and within two minutes, at just after 5:00 a.m., the Acorn was moving. As the vessel left the dock, the stunned spectators listened in solemn silence to the Rev. Daniel Foster, who asked them to kneel and pray for “the poor brother who is carried by force to the land of whips and chains.”

Boston, the birthplace of the struggle for America’s liberty seventy-five years earlier, had returned her first person – a free man in the North – back to slavery.

Discussion questions

Were there any events or developments that you had no knowledge of prior to reading the book, such as the Great Fire of 1872, or the Great Railroad Jubilee?

Of the events and developments highlighted in A City So Grand, which do you think had the most profound impact on the city of Boston or the nation? Why?

Could something have been done differently to prevent federal troops from returning Thomas Sims to captivity? Do you think word was leaked of the Vigilance Committee’s plan to rescue Sims?

What were your thoughts in reading about Sims being marched through the streets of Boston to the deck of the Acorn for his return to slavery? Can you compare it to any other historic events/moments, in Boston or elsewhere?

How familiar were you with the struggles — and resilience — of Boston’s Irish population? What aspect of their plight did you find the most poignant?

Imagine that the affluent Back Bay neighborhood does not exist, and developers today are working up plans for the massive landfill project. Would the project be as successful today? As profitable? As efficient? What obstacles would exist today that weren’t an issue in 19th century? What resources/technology would make it easier for today’s developers?

The city of Boston rebounded in a remarkably quick manner to the devastation of the Great Fire of 1872. Despite a financial depression, the city’s businesses and government worked together to rebuild. If the fire were to happen today, would the rebuilding be as fast and efficient?

Would you say that Boston is best known for its prominence in education, medicine, or its historic milestones in the building of our nation? How did your perception of Boston change after reading A City So Grand?

What impressed you most about the events of Boston in the second half of the 19th century? What did you find most disappointing?

If you could highlight only one section of the book to illustrate the character of the City of Boston, which would it be and why?

If you hadn’t been involved with this book discussion, would you have chosen to read A City So Grand on your own? Do you typically read non-fiction or history?

After reading A City So Grand, do you want to read other books about related topics (Boston history, abolitionists, the Civil War, the history of railroad transportation, anything written by Steve Puleo?)

More

Interview with The Patriot Ledger

Can-do attitude turned Boston into a great city

By Lane Lambert

The sites are familiar to anyone who visits Boston – the MBTA’s Park Street subway station; the Back Bay’s European elegance; and the Boston Common memorial to the 54th Massachusetts, one of the first official black regiments in the Civil War. For author and longtime Weymouth resident Stephen Puleo, those places are far more than tourist stops. They’re landmarks of public projects and the anti-slavery movement, all of which transformed Boston into a world-class city within the span of 50 years, from 1850 to the turn of the 20th century.

Puleo, a communications consultant and Suffolk University lecturer, chronicles those events in his latest Beacon Press book, A City So Grand: The Rise of An American Metropolis. In his first extensive interview, he talks about Boston’s important forgotten figures of the era, and why a disastrous 1872 fire turned out to be a good thing

What was your first encounter with Boston’s history?

I grew up in Burlington, but my dad grew up in the North End, so he took me there frequently when I was a boy. It’s a neighborhood with both Revolutionary War history and Italian heritage, and I’ve loved Boston history since then.

Boston is most famous for its colonial past, and known today as a university, financial and high-tech center. What turned your attention to the post-1850 decades?

It’s a period that’s largely unwritten about. Boston makes this huge transition from being a large town to a world-class city. By the dawn of the 20th century, Boston was as influential as New York, Paris and London. In this period, the word “no” wasn’t in Boston’s vocabulary. Projects like the development of Back Bay and the building of the subway combined private and government cooperation – a sense of common spirit in ways that don’t exist today. Some of it was born out of necessity. The Back Bay was a polluted eyesore, and the city needed more room from the inf lux of Irish immigrants. They needed a plan to keep wealthy families from fleeing the city. The subway was also seen as a way of making Boston a modern city.

But you say the whole transformation really started with the abolitionist movement of the 1850s, before the Civil War.

Boston was anti-slavery for a number of reasons, partly from the religious and educational tradition. But the case that really galvanized the movement was the return of the runaway slave Thomas Sims from Boston to his master (in 1851), from the Fugitive Slave Act. There were a lot of firebrands, but they were talkers, not doers, and the Sims case humiliated them.

And then there’s the subway.

The subway was the other can-do project. It opened up downtown streets that were congested (by trolleys), and it connected the city to outlying neighborhoods … and eventually to nearby towns. The Boston Elevated system connected the city first. By about 1915, the total system – the subway underground around the center city, and the elevated emanating from that – was complete.

The downtown fire of 1872 was the worst of the time except for the famous Chicago fire. Now it’s an almost forgotten episode.

It had a great impact at the time. It burned 65 acres and hundreds of buildings. But it also showed Boston’s resilience. The whole area was rebuilt in two to three years. The whole hydrant system was improved, along with water lines and natural gas flow. So good comes out of that, too.

When historians look back at our era 100 years from now, are there any projects that will compared to the scale of Back Bay, the subway and the abolition movement?

One thing would be the current immigration of mostly Asians and Hispanics, though it’s happening in different ways from the Irish and Italian immigration of the 19th century. I would hesitate to compare the Big Dig to Back Bay, because the Back Bay development went quite smoothly, and the state actually made a profit on it. The breadth of the Boston area’s transportation system might be a comparison. The MBTA has expanded across Greater Boston – and look at the highway system built in the 1950s and ’60s. That certainly changed the South Shore. And I hesitate to compare something like the Vietnam War protests to the abolition movement. That was about slavery, owning people as chattel. Nothing compares to that.

Could a mega-project like Back Bay or the subway be done today?

I don’t know if it could. Every good idea is a little ahead of its time, and in the media environment we live in now, a very small number of people can protest with an influence far beyond their numbers. That discourages the sort of risk-taking and putting forth of great ideas you saw in Boston in the late 1800s. Today some great ideas get stopped in their tracks.