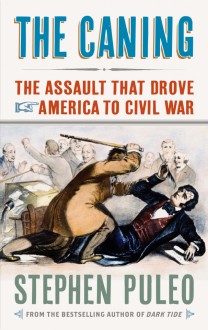

The Caning

The Assault That Drove America to Civil War

Early in the afternoon of May 22, 1856, ardent pro-slavery Congressman Preston S. Brooks of South Carolina strode into the United States Senate Chamber in Washington, D.C., and began beating renowned anti-slavery Senator Charles Sumner with a gold-topped walking cane. Brooks struck again and again—more than thirty times across Sumner’s head, face, and shoulders—until his cane splintered into pieces and the helpless Massachusetts senator, having nearly wrenched his desk from its fixed base, lay unconscious and covered in blood. It was a retaliatory attack. Forty-eight hours earlier, Sumner had concluded a speech on the Senate floor that had spanned two days, during which he vilified Southern slaveowners for violence occurring in Kansas.

Brooks not only shattered his cane during the beating, but also destroyed any pretense of civility between North and South. One of the most shocking and provocative events in American history, the caning convinced each side that the gulf between them was unbridgeable and that they could no longer discuss their vast differences of opinion regarding slavery on any reasonable level. The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War tells the incredible story of this transformative event. While Sumner eventually recovered after a lengthy convalescence, compromise had suffered a mortal blow. Moderate voices were drowned out completely; extremist views accelerated, became intractable, and locked both sides on a tragic collision course.

The caning had an enormous impact on the events that followed over the next four years: the meteoric rise of the Republican Party and Abraham Lincoln; the Dred Scott decision; the increasing militancy of abolitionists, notably John Brown’s actions; and the secession of the Southern states and the founding of the Confederacy. As a result of the caning, the country was pushed, inexorably and unstoppably, to war. Many factors conspired to cause the Civil War, but it was the caning that made conflict and disunion unavoidable five years later.

Reviews

Russell S. Bonds, author of War Like the Thunderbolt: The Battle and Burning of Atlanta

Preston Brooks’s notorious beating of Charles Sumner on the floor of the United States Senate perfectly encapsulates the politics, passions and prejudices that ignited the Civil War. Stephen Puleo’s beautifully written, compelling account of the caning and its aftermath presents the often-overlooked drama of the late 1850’s, illuminating a cast of fascinating characters — not only Brooks and Sumner, but Stephen Douglas, John Brown, and Abraham Lincoln — just as they step from the wings onto the great stage of history. The Caning is an engrossing story of violence made more resonant by our awareness of the bloodbath still to come, and essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the Civil War and its causes.

The Boston Globe

Kate Tuttle – November 3, 2012

In 1856, when South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks brought his cane down upon the head of Charles Sumner, senator from Massachusetts, he beat Sumner so hard the cane splintered. According to Stephen Puleo, the assault on the Senate floor— and especially the radically different reactions to it in the North and the South — triggered a chain of events leading straight to the Civil War. The country had debated the role of slavery for nearly a century, but the caning heightened already intense disagreements, especially over the status of new states such as Kansas, which was the primary battleground before the war began. After Brooks’s attack, northern newspapers decried its brutality, seeing it as an insult to free speech and indication of southern barbarism, while many in the South applauded. “Hit him again,” editorialized Brooks’s hometown paper.

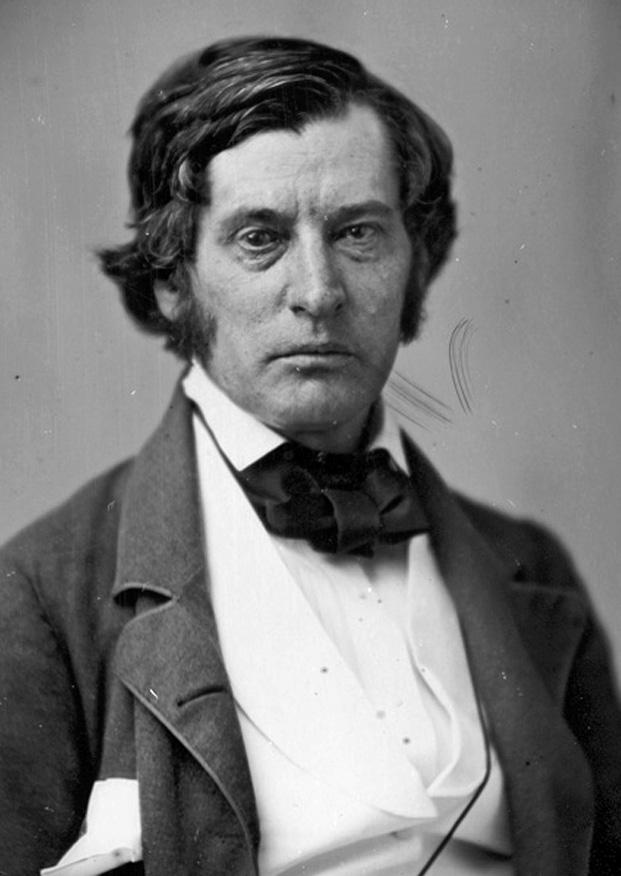

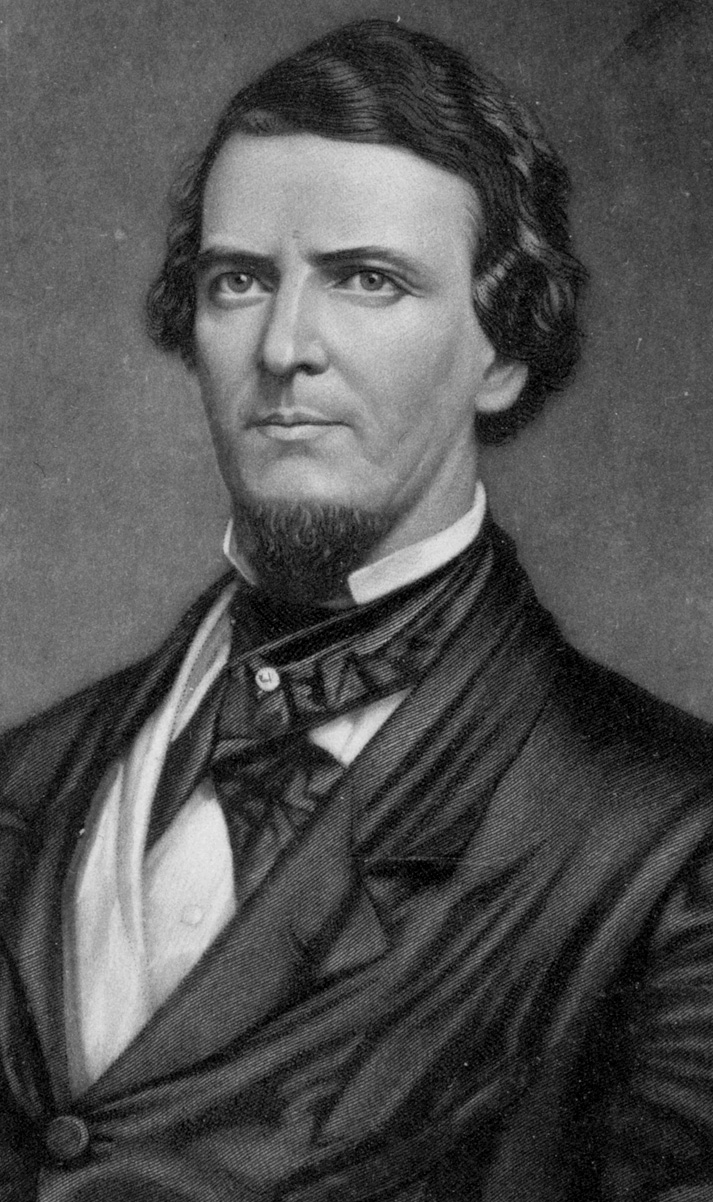

Puleo tells the story vividly, masterfully distilling its sprawling context. Yet at times he seems curiously tone deaf, repeatedly extolling the virtues of compromise when, of course, slavery is an issue about which compromise is impossible. He’s at his best when chronicling the lives of the two men at the heart of the caning. Infamously prickly and intense, the fiery abolitionist Sumner was, according to a friend, “almost impervious to a joke”; still, his steadfast devotion to principle commands respect. For his part, Brooks had been infuriated by Sumner’s recently delivered speech about the turmoil in “Bleeding Kansas,” in which he had insulted Brooks’s cousin, Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina. Brooks limped from an earlier duel wound; the code duello (literally rules for duels) was just one part, Puleo writes, of “a code of honor that governed virtually every aspect of a white Southern gentleman’s life.” One country, two civilizations.

Fredricksburg Star

Elizabeth Rabin – October 28, 2012

On May 22, 1856, Preston Brooks, a congressman from South Carolina, beat Charles Sumner, a senator from Boston, in the Senate chamber with a malacca cane. Time and distance makes this statement now sound like an accusation from the game Clue. But in the years before the Civil War, Brooks’ act signaled the widening distance developing in contemporary American society.

Abolitionist rhetoric and pro-slavery response had led from fiery words to physical violence that spread even to the halls of American government. Stephen Puleo’s latest nonfiction book, The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War, focuses on the confrontation between Brooks and Sumner and explores the events that led up to it.

Puleo’s book is an accessible, interesting read for those who are curious about the Civil War but may be intimidated about where to start.

Sumner was a Boston native who fought what he thought was the good fight against slavery by using the most inflammatory remarks at his disposal. Brooks was a young Southern man determined to avenge what he felt were personal insults toward his land and his family, even if it meant violence.

Readers will not only find The Caning a compelling read, but they may be surprised to find multiple parallels to today’s political climate. The debate over the legality of slavery often hinged on what was or wasn’t explicitly spelled out in the Constitution, much like many hotly debated issues today. Many editorials of the day insisted that “apathy was not an option . . . nor were insipid calls for calm, reason or cooler heads.” Again and again, citizens from both pro-slavery and abolitionist states emphasized how they were incapable of even understanding their opponents’ arguments.

As our current political discussion continues to be stormy, these same sentiments come up whether the issue is health care or the federal deficit.

With attitudes like these in 1856, violence, not just between statesmen, but between American citizens was inevitable. The time for talk was over; many illustrations of the caning acknowledged this by showing Brooks’ cane overcoming Sumner’s pen. While The Caning may be a jumping-off point for history buffs in the making, the book is also a grim reminder of what can happen when a healthy debate becomes a polarizing argument that neither side is willing to lose.

Barnesandnoblereview.com

Paul Di Filippo – November 23, 2012

The famous but vaguely recalled historical incident is generally referenced whenever a commentator wishes to indicate the depths of internecine strife to which the United States once descended, and which the country is possibly in danger of reaching again. Typically, we hear, “Divisive as things are today on the political scene, they can’t compare to the days just prior to the Civil War, when one politician actually beat up another on the floor of the Senate.” Then the argument moves on, with the rhetorical touchstone having been lightly and carelessly stroked.

But behind all such bland, automatic, and generic references lies an absolutely fascinating and complex story, full of rich specifics. Author Stephen Puleo has invested a huge amount of intelligent research into the matter — the events surrounding and including the moment on May 22, 1856, when Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina thrashed Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts with a gold-topped wooden cane on the floor of Congress — and he has cast the facts into The Caning, a compulsively readable narrative which does honorable, evenhanded justice to all the players and issues of the era, while teasing out not only similarities with our present antagonistic politics but also some educational differences.

Part I of Puleo’s story succinctly and cogently establishes the national conditions and political currents leading up to the public beating. Currently at the center of the burgeoning anti-slavery debate was the state of Kansas, recently deemed acceptable to host slavery by no less an authority than President Franklin Pierce. Several famous cases of runaway slaves restored to their owners also inflamed feelings on both sides of the issue. Senator Sumner, dogmatically abolitionist, chose to deliver a two-day, multi-hour speech ranting against the Kansas decision and many other topics, in which he gratuitously insulted his colleague, Senator Butler of South Carolina. Here we pause dramatically to flash back to the birth of Sumner and the familial and personal characteristics that shaped him into an emotionally constricted yet principled ideologue.

Part II brings us up to the cliffhanger moment of the caning, and also focuses on Preston Brooks, the antagonist, revealing with lucid details the antithetical societal and cultural forces that shaped the Southern partisan, a man for whom, unlike his opponent, family and honor outweighed everything.

Part III opens with the central Chapter Eleven, “The Caning,” a mighty tour-de-force of vivid reenactment. The reader feels a tingling “you are there” set of thrills. This section continues with the incredibly complicated aftermath and fallout of the assault, which was taken up by both Northerners and Southerners as an emblematic torch for their respective causes. From the vigilante actions of John Brown to the dignified yet fervent speeches of Lincoln, Sumner and Brooks served as irreplaceable talismans and goads to action. This section climaxes with the untimely death of Brooks from an infection, followed by his cis-Mason-Dixon canonization.

Part IV traces the widening ripples of the altercation, from its impact on the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision (“perhaps the most controversial American judicial decision in history”), through John Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid and Lincoln’s election. Along the way we get the heroic and pathetic return of a still debilitated Sumner, four years after his caning, to the Senate for a final rabble-rousing speech. Puleo caps everything off with an account of Sumner’s death in 1874 — an era intimately connected with 1856 yet incredibly distant too — and an assessment of how history has treated each principal in the battle.

The elements of this tale that pertain directly to the concerns of 2012 are myriad and vital, rendering this book an important lesson as well as an entertaining excursion to the past. The way that even a noble cause like abolition can be seduced into supporting outlaw actions such as those of John Brown. The role of the media in stoking the fires of contention. (Puleo lists a mere sampling of the dozens of newspapers he surveyed.) The impact of bias confirmation in determining our political stances. The divergent roles of high-minded and demagogic politicians. So many similarities both inspire and cause despair at how little has changed in human nature.

The strangenesses of this era are the other side of the coin. For one thing, Puleo’s account make these actors and their causes seem positively Shakespearean compared to our own times. I don’t think it’s mere distance that elevates the discourse and stakes. I just can’t fathom anyone one hundred years from now writing an equally lofty and tragic tome about the 2012 elections. Nor is it completely possible to compare Springsteen to Longfellow, or Jon Stewart to Ralph Waldo Emerson. And, in a trivial but gratifying manner, the reader also encounters many quaint and charming tokens of the past. Jefferson Davis addressing the citizens of Boston from the balcony of Faneuil Hall?! I particularly liked the tribute offered to Sumner by the inmates of the Boston Female Orphan Asylum, “where young girls were lined up in front of the building waving handkerchiefs and displaying on a white banner a wreath of evergreen covered with flowers, along with a sign that read: ‘We weave a wreath for Charles Sumner.’” And the loony French doctor who treated Sumner with applications of burning cotton wool along his spine is pure steampunk.

In deftly and charmingly explicating this ancient scandal, Stephen Puleo has simultaneously rescued an important part of America’s heritage while shining a light that helps illuminate our forward path.

Excerpts

Many factors—love of family, loyalty to region, reliance on slavery, adherence to the code of honor—weighed heavily on Preston Brooks as he approached Charles Sumner’s desk in the Senate chamber on May 22, 1856.

But the growing bombast and all-out assault by abolitionists and their ilk also drove him. Since the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act two years earlier, when Southerners openly talked of secession if the legislation failed, Northern abolitionists had only grown bolder and more radical. They denigrated the South and her way of life at every turn, they preached emancipation without compensation, they portrayed Southern planters as brutes and criminals, they encouraged insurrection by slaves—and now, with Sumner as their vocal spokesman, they assailed efforts by Southerners to admit Kansas to the Union as a slave state. The situation was perilous; the South’s right to exist as a slave society was in jeopardy. “If abolitionism be successful in Kansas,” warned one Southern newspaper, “we believe the battlefield of Southern rights will be brought to our own doors in less years than the life of a man.”

These overall attacks, plus Sumner’s “gross insult to my State . . . and uncalled for libel . . . on my blood” left Preston Brooks with little choice. Later he would say that he would have “forfeited my own self-respect, and perhaps the good opinion of my countrymen,” if he had not “resented the injury enough” to call Sumner to account.

Despite his loathing for Charles Sumner, Preston Brooks did not intend to kill him. A fellow congressman would later say that had Brooks decided to make Sumner pay by “pulling his nose” or “slapping his face,” events might have turned out much differently. But the irate Brooks viewed Sumner’s sins as demanding a more severe form of punishment. A duel was a possibility, but two factors caused him to dismiss this idea: first, Sumner was not a man of honor and thus was unworthy of such a gentlemanly form of settling disputes; second and most important, Brooks feared Sumner would brush aside a challenge to duel and institute embarrassing legal proceedings against Brooks for “sending a hostile message,” in addition to any injuries Sumner suffered in a duel. Brooks noted that these charges would “subject me to legal penalties more severe than would be imposed for a simple assault and battery.”

Brooks also thought about using a horsewhip or cowhide to flog Sumner, but feared the larger, stronger Sumner would wrest either weapon from his hand. “[He] is a very powerful man and weighs 30 pounds more than myself,” Brooks told his brother. If Sumner disarmed him, Brooks perhaps could be forced to draw a pistol and “been compelled to do that which I would have regretted the balance of my natural life.”

Instead, to “expressly avoid taking [a] life,” Brooks decided to punish Sumner using an ordinary, easy-to-grip cane made of gutta-percha wood, which a friend had given him three months earlier. The cane weighed eleven and a half ounces, had a gold head, and tapered from a thickness of one inch at the large end to three-quarters of an inch at the small; it had a hollow core of about three-eighths of an inch.

Because the cane was not solid, it was likely to splinter if and when it struck the head or torso.

Discussion questions

- Had you heard about the beating of U.S. Senator Charles Sumner prior to reading The Caning? If not, how surprised were you by the incident?

- While reading about these brutally divided pro- and antislavery politicians, what were your thoughts about accusations of partisan bitterness in U.S. politics today? Did your views change? Are today’s battles mild by comparison?

- The Caning offers detailed biographic profiles of both Charles Sumner and Preston Brooks. Congressman Preston Brooks, who conducted the assault, may be the obvious antagonist. However, as you learned more about him, did you find him to be a more sympathetic character? What qualities, if any, did you find appealing?

- In your view, what were Charles Sumner’s strengths and weaknesses? And what was most appealing, and least appealing about him? How much did you know about him before reading The Caning? Were you surprised he is not a more widely recognized historical figure?

- Imagine that the assault on Sumner never occurred. Would it have taken longer to push the country into war? How might the path to war have differed? In your view, how significant a factor was the caning to the start of the Civil War?

- The Caning is filled with information about the pre-Civil War tension between pro- and antislavery forces. Aside from the beating of Sumner, which event — a speech, an act of violence, the Southerners’ support of Brooks — did you find most shocking or surprising?

- How familiar were you with the details of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which stated that the future of slavery in those territories would be decided by the popular vote of residents? Can you draw any parallels to other debates/conflicts in U.S. history?

- If you hadn’t been involved with this book discussion, would you have chosen to read The Caning on your own? Do you typically read non-fiction or history?

- After reading The Caning, do you want to read other books about related topics (Boston or Southern history, abolitionists, the Civil War, anything written by Steve Puleo?)

Buy The Caning

To order The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War, click on a link below.

More

Steve traveled to Washington D.C. to tape an appearance C-SPAN’s weekly interview show, “Q&A,” hosted by Brian Lamb. Steve was thrilled with the opportunity to discuss The Caning, and is indebted to Brian, as well as to C-SPAN producer Mark Farkus and the entire C-SPAN team for their hard work and hospitality. The show, which is available for replay, aired on Sunday, June 21, and Monday, June 22, 2015.

Weymouth author asserts act of violence on Senate floor led to Civil War

By Robert Knox – Boston Globe Correspondent

As a divided nation faces a close election and recalls the 150th anniversary of polarization’s worst case scenario — the Civil War — a new book focuses on an act of violence in 1856 that turned moderates into hard-liners and made war almost inevitable.

Two days after Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, the country’s most prominent abolitionist, made a five-hour speech attacking slave owners and singling out a Southern senator for personal abuse, South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks attacked him in the Senate chamber, beating him almost to death with his cane.

“The Caning,” the title of Weymouth author Stephen Puleo’s new book, had “enormous impact” on subsequent events that led to the war between the states, according to the author.

“The caning is the no-turning-back point on the road to the Civil War,” Puleo said last week from his home.

The South responded to Brooks’s attack by pleading, as a front page editorial put it, “Hit Him Again.” In the North, the new anti-slavery Republican Party experienced a meteoric growth in membership and importance. Later that year its first presidential candidate nearly won election without a single electoral vote from the South.

In 1858, Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney, a slave owner who felt his home and way of life were under attack by abolitionists like Sumner, delivered a stunning opinion (in the Dred Scott case) essentially banning all federal attempts to regulate the spread of slavery. In 1860, when Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected, secession quickly followed.

Puleo is the author of five books, including the bestselling Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919. His books have garnered favorable reviews from The New Yorker, The Boston Globe, and The Providence Journal, among other publications, and been chosen by more than 50 book clubs.

His previous book, a history of Boston released two years ago titled A City So Grand, was praised by novelist Dennis Lehane as “a book so grand.” “It’s been quite awhile,” Lehane wrote, “since I’ve read anything so enthralling.”

Between the statesmen of the Revolutionary period and 20th-century “Irish politicians” such as James Michael Curley and John F. Kennedy, Sumner is the state’s most important political figure, Puleo said. Although his name is less well known today, his statue on Boston Common is identified by a single word, “Sumner,” because its makers believed that was all Boston would need to know.

Sumner was an abolitionist rather than a compromiser on slavery at a time when that stance was highly controversial even in the North, as well as a powerful speaker, and public enemy number one to pro-slavery Southerners. But though “a true giant” in the anti-slavery cause, Sumner “was not a likable guy,” Puleo said. “He was arrogant, condescending, estranged from his family.”

Even as he was being assaulted, others didn’t rush to his aid. The language of his personal attack on Senator Andrew Butler — whom he described as possessing “a mistress who, ugly to others, is always lovely to him. I mean, the harlot, Slavery” — shocked even supporters.

Brooks, on the other hand, was a “nice guy,” loved by his family and regarded as a moderate, a compromiser capable of working with Northern politicians. The intent of his assault, Brooks said, was “to teach [Sumner] a lesson” for attacking his second cousin, Butler.

“Part of the Southern code of honor was whoever insults my state and my kin insults me,” Puleo said.

Sumner suffered serious and lasting injuries from the attack and was out of the Senate for three years, and Northerners were shocked even more by the South’s embrace of this act of violence. Northern moderates began to think “maybe we cannot reason with these people on the subject of slavery,” Puleo said.

Southerners in turn were outraged by what they saw as the North’s hypocrisy, since Northern manufacturers were making fortunes from slave-picked cotton, Puleo said. They also believed Northerners’ condemnation of slavery was hypocritical because in the “free” North, poor immigrants were permitted to live in conditions worse than those of slaves — in Boston, for example, Irish immigrants were discriminated against and abandoned to lives of poverty. “[Southerners] said, ‘Who are you to pass judgment on us?’” Puleo said.

Brooks was charged with assault and fined $500, and Southern supporters raised money to pay it for him. After a vote to expel him from the House failed to get the needed two-thirds majority, Brooks resigned his seat, only to run in the special election to replace him — and “wins unanimously,” Puleo said.

But Brooks’s caning of Sumner sowed the wind of violence in a divided land, and the no-longer “united” states would reap the whirlwind in four years of the deadliest war in the country’s history.

Polarizing politics

Author explores assault on Massachusetts senator

By Jody Feinberg – The Patriot Ledger – October 2012

Historian Stephen Puleo tells a story about an incident in Congress in 1856 that shocks his listeners, even those dismayed with today’s political attacks.

Inside the Senate chamber, pro-slavery U.S. Rep. Preston Brooks of South Carolina beat unconscious anti-slavery Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts with his gold-tipped walking cane. For more than a minute, no one intervened to stop the assault.

Brooks was enraged that Sumner had delivered a powerful speech that vilified Southern slave holders, as well as insulted his second cousin. Afterwards, the South lionized Brooks.

“People are amazed that it happened,” said Puleo of Weymouth, who recreates this watershed event in his new book. “We’re forever hearing how polarized things are now, that it’s never been this bad. Well, it was.”

During the next two months, Puleo will speak at six South Shore libraries and venues about his book, The Caning: The Assault that Drove America to Civil War. The first is Oct. 15 at the Bathhouse Lecture Series in The Nantasket Beach Resort in Hull and the last is Dec. 13 at Thomas Crane Library in Quincy.

Researching over two years, Puleo traveled to South Carolina to read thousands of letters, newspaper accounts, and other original documents. With a novelist’s gift, he has drawn upon them to dramatically convey the characters, issues and consequences of the caning.

“I try to combine impeccable extensive research with good story telling,” said Puleo, author of five previous histories and adjunct professor at Suffolk University. “To me that’s the way to show that history is exciting and interesting.”

Puleo, who grew up in Burlington and studied English at UMass Boston, worked in corporate communications and public relations before becoming an academic and author.

At age 40, he returned to UMass to get his master’s degree in history, writing his thesis on Italian immigrants in New England, which led to his first book in 2003, Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919. He has lived in Weymouth for 25 years with his wife, Kate Puleo, the principal of St. Jerome School in North Weymouth.

“The caning is not the cause of the war, but it makes it inevitable,” Puleo said. “It inflames passion and drowns out moderate voices. It makes compromise not a virtue, but a weakness. After the caning, there was no way the slavery issue could be settled peacefully.”

The event also is relevant to today’s regional differences, he said. “Despite the Internet and travel, there still is a kind of North/South rift,” Puleo said. “Lots of stereotypes that both sides had, and that were made stronger after the caning, exist today. “It’s good to know where these perceptions have their roots, because it can help overcome differences.”

Puleo also said he hopes the book brings recognition to the man who was the North’s strongest voice for abolition, but now is largely unknown and overshadowed by Boston’s Revolutionary era heroes.

The book’s photographs include statues of Sumner in the Boston Public Garden and on the Harvard University campus. His home still stands on Hancock Street on Beacon Hill, and a Roslindale elementary school bears his name (the Sumner Tunnel was named after the general and legislator William Sumner).

“Exactly who he was and why he was important eludes most Bostonians,” Puleo wrote in the book. “No man did more to influence the slavery debate on a national scale. Southerners detested and sometimes feared him. Northerners first resisted and then came to revere him. “But when Charles Sumner spoke, everyone listened.”

For his part, Puleo is humbled that people read his books and listen to his talks. “I like doing a little evangelism on history, which needs it more than ever, and I love meeting readers,” he said.

“I’m honored and immensely grateful.”