The Boston Italians

A Story of Pride, Perseverance and Paesani, from the Years of the Great Immigration to the Present Day

This story of the Boston Italians begins with their earliest years, when a largely illiterate and impoverished people in a strange land recreated the bonds of village and region in the cramped quarters of the North End.

Focusing on this first and crucial Italian enclave, The Boston Italians describes the experience of Boston’s Italian immigrants as they battled poverty, illiteracy, and prejudice (Italians were lynched more often than members of any other ethnic group except African Americans); explains their transformation into Italian Americans during the Depression and World War II; and chronicles their rich history in Boston up to the present day.

Much of the story is told from the perspective of the Italian leaders who guided and fought for their people’s progress, reacquainting readers with pivotal historical figures like James V. Donnaruma, founder of the key North End newspaper La Gazzetta del Massachusetts, now the English-language Post Gazette, and politician George A. Scigliano.

The book’s final section is devoted to interviews with Boston Italian Americans. The story of the Boston Italians is among America’s most important, vibrant, and colorful sagas, and necessary reading for anyone seeking to understand the heritage of this ethnic group.

Reviews

- “Stephen Puleo breaks new ground and dispels old myths about Italians who settled here.”

The Boston Globe - “The Boston Italians is a thorough, readable and detailed recapitulation of the Italian experience in America and Boston.”

The Providence Journal - “Puleo captures the spirit of proud, hard-working people who rallied around each other to make a better life.”

The Patriot Ledger - “Puleo has crafted an unsparing, but mostly admiring, account of a colorful and vibrant community as it battled for social acceptance and political recognition.”

Michael Kenney, The Boston Globe - “I strongly recommend that everyone read this masterfully written book.” Read the review from The Post-Gazette

- “Puleo has honored our ancestors by telling their story truthfully and with compassion.” Read the review from Lo Specchio

“At long last, a historically accurate and well-crafted history of the Italian community that flourished in Boston’s North End. Drawing upon original documents, as well as anecdotes from the lives of his own family, Stephen Puleo has produced a work that is a great read for the generalist and a gold mine of information for the specialist. The Boston Italians is the inspiring story of a people who rose from poverty and discrimination to become a prosperous and productive part of Boston’s colorful history.”

– Thomas H. O’Connor, university historian at Boston College and author of The Boston Irish

“This vivid, engaging and well-researched account of Boston’s rich Italian heritage is an inspiring contribution not only to the history of the city, but to the story of America. Part elegy, part paean, The Boston Italians is a compelling document that honors the generations of immigrants who inspired it.”

– Chris Castellani, author of The Saint of Lost Things and A Kiss from Maddalena

Post Gazette

(Formerly La Gazzetta del Massachusetts)

Boston, MA

By Claude Marsilia

August 10, 2007

Author Stephen Puleo’s 130 years of history has moved me as no other book of its kind ever has. For me it is a refreshing and intelligent beginning of what I suspect will be considered a historical classic novel of the Boston Italians.

Puleo doesn’t mince words. He is direct and forthcoming. His introduction is so definitive that no one will misread his intents. And that is to introduce, in particular, the Italian immigrants of Boston, and justifiably praise their efforts to the highest degree. His voice rings loud and clear proving ultimately that these Italians embody the best as citizens of America. He takes on a daunting task attempting to justify the wholesale immigration of Italians to America, a country that would be inferior to them. They came in droves hearing and believing the stories of the rich Americans. Initially, they didn’t know their chances for success were limited.

Immediately, Puleo writes about two preeminent Bostonians, James Donnaruma, founder of La Gazzetta and George Scigliano who were the chief spokesmen and defenders of Boston’s Italian immigrants. Puleo writes, “Here (Scigliano) was a man with education, financial wherewithal, and political influence who provided leadership to people who had none of these things.” He adds admirably, “he embodies the Italians’ spirit, pride, and hope.” On the other hand stood Donnaruma who ten years after arriving in America began his publishing career which flourished and spawned the highly successful newspaper initially called, La Gazzetta. This newspaper became his pulpit which he used judiciously and with grace. With his influential newspaper he spoke to and for the overwhelming illiterate Italians who lived primarily in the North End and East Boston. The early death of Scigliano placed Donnaruma as the leading spokesman for the under privileged Boston Italians.

Puleo’s alarming description of living conditions in the North End is difficult to absorb.

It was an incubator den. Apparently, Italian immigrants were susceptible to a variety of diseases because of their living conditions and the hazardous jobs they held. Puleo doesn’t waste any time voicing the unscrupulous feelings of the general public, against the Italian immigrants during these difficult times. Read the following gripping testimony by a Yankee reporter, “No where in Boston has father time wrought such ruthless changes as in the once respectable quarter (North End), now swarming with Italians in every dirty nook and corner.” The reader will be uncomfortable reading some of Puleo’s narrative, but the reader won’t be able to drop his book. He will become transfixed and knows he must read on to see what Puleo has to say next.

Unrelenting, Puleo approaches the rivalry between the Boston Irish and the immigrant Italians. This rivalry continued despite the fact they both were mainly Catholic. The second generation of these two ethnic groups began to solve the problem by marrying one another. Today I suspect there are few Irish families who do not have an Italian in their family and vice versa.

I have never read a more candid and unequivocal book on the status of the Boston Italians since their arrival in America. Some readers, I suspect, will stiffen their backs when they read this book while others will nod their heads in assent. Puleo explains precisely how and why the Italians of the North End progressed from mere living there to embracing the fact that the neighborhood was their own. It seems as though the Italians were building their own subculture in America and living at a subsistence level which was more important to them than deeper education. Apparently they felt it was more central and safer for the family to live in their own enclave rather than reaching out beyond their neighborhood. This chosen way of life would become their mantra.

Puleo explains succinctly the three major reasons for leaving Italy for America, rampant malaise, devastating earthquakes, and constant losses of farm income caused by excessive taxes and stagnant recovery creating abject poverty, la miseria. Many of the immigrants consoled themselves by considering their immigration temporary. They found it difficult to forget their past. They became known as birds of passage because they sent their earned money back to their relatives in Italy. Something I never considered was Puleo’s remark how the money sent back benefited the Italian government.

The truth can hurt at times but Puleo does not hesitate to denote the facts with outmost confidence. He explains, when the Italians cloistered in enclaves- “This hindered their acceptance which prevented their advancement, and fueled discrimination so white-hot and intense that Italians were among the most vilified immigrant groups ever to arrive on America’s shores.” I’m on Page 66 of this remarkable book and I need to take a respite and consider the overwhelming nature and factual accountability expressed by Puleo. This emotional recess I am experiencing must be because of the somewhat similar experience my immigrant parents had. My mother who was born in Rome and whose family was upper middle class, though never outwardly expressed, did not want to leave her home in Rome. My father, on the other hand, was born in Salerno, Italy, however, his ancestry is French with a Greek surname. He was forced to leave Italy because of his anti-Mussolini views. There are no records of his arrival in America, therefore we, the family, surmised he came here clandestine.

I would like to return to the amazing James Donnaruma. He was way ahead of his time even though he was an immigrant like most of his readers. He realized the importance of achieving citizenship and the importance of political influence. At sixteen he established an Italian newspaper that would be the bully pulpit for the Italian/Americans. Today this outstanding newspaper, known as the Post Gazette, which has been continuously published for 112 years and now ably managed by a sophisticated, lovely, young woman, Pamela Donnaruma, granddaughter of James Donnaruma. Puleo’s admiration for James Donnaruma is obvious, read this. “Donnaruma was a mover and a shaker, a power broker who was well aware that his ability to get things done depended on his persuasiveness in English.”

As time went on Puleo clearly notes, by the following remark, how the image of Italians was changing. Initially, stereotypes of Italians were defined as shiftless and lazy.

A city official observed, “We can’t get along without the Italians.” In addition, “We want someone to do the dirty work: the Irish aren’t doing it any longer.” Puleo’s coverage of the Boston Italian’s history is all encompassing and at times very personal. He explains how his grandmother, Angela Puleo after living in the North End for nearly thirty-five years was still registered, as an “Enemy alien” (1942).

A shocking revelation by Puleo was new to me. He reveals that a communiqué written prior to World War I, from the German foreign minister to the German minister in Mexico, indicates if they were to form an alliance with Germany their reward would be the return of “lost territories” of New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona.

Puleo’s writing skills come to the fore when he writes about the insurgency of the Mafia during the time of prohibition. Though many mobs were controlled by Irish and Jewish racketeers, the Italians seem to capture the headlines by the sheer force of their personalities, such as, Al Capone, Frank Costello, and the notorious Charles “Lucky” Luciano.

Justifiably, Puleo praises James Donnaruma again and again. Puleo tells of the continuous help he gave to the Italians financially and otherwise. At times creating financial distress but never missing an issue, a trait that is evident in his granddaughter, Pamela Donnaruma’s DNA, who never missed an issue, either. To learn that icon James Donnaruma supported R.H. Hoover set me back a bit, however, he was easily forgiven by me because of his unflagging commitment to the greater Boston Italians which was unwavering and sincere.

Once again Puleo reveals his broad spectrum of history especially when he writes about the rise of Germany led by Hitler who used the humiliating Versailles Treaty of 1919, to shackle Germany and its people; to entrench his political position. Eventually Hitler’s demagoguery resulted in Germany’s disaster. Puleo’s deliberation of President Roosevelt during the depression is classic and refreshing to read. If there ever was any doubt about the loyalty of Italians toward America it was completely defused by the onset of World War II. Read this, “When more than one million Italian Americans were among the sixteen million soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines of all ethnic and geographic groups who donned American uniforms during World War II.” Puleo writes further, “… more than fifty thousand captured Italian soldiers were interned in twenty-seven POW camps throughout the United States,” I personally witnessed Italian POWS that were interned at the Don Bosco School on Paris Street, East Boston. Every day, but Sunday, they marched to the East Boston piers and worked as longshoremen. What a sight.

Puleo’s writing tempo is upbeat. Historical books generally have trouble holding the reader’s attention. Puleo does not, because he is more than capable to hold the reader’s attention by combining historical events with known personalities. Puleo writes about the decline of the Italian/Americans that lived in the crowded North End of Boston. Today Puleo states the North End has less than 40% Italian/Americans. Nevertheless, “… it retained its character, reputation, and heritage as one of the nation’s best-known Italian neighborhoods.”

On May 7, 1953, James Donnaruma died and his son Caesar became the editor. He quickly alters the course of the paper by publishing it in English. Next, his political feelings were more intuned with the Democratic Party, evident by his total support of John F. Kennedy. In addition, Caesar’s financial expertise resulted in the paper to become more profitable. Following Caesar’s retirement in 1971 his fabulous wife, Phyllis, took over as publisher and editor. For nineteen years wonderful Phyllis never missed a beat. Fortunately, I had the distinct pleasure of knowing Caesar and Phyllis whom I admired and loved. In June of 1989, at the age of eighty-nine Caesar passed away.

The final pages of Puleo’s book are devoted to noting the major successes of Italian Americans in business, education, medicine, and politics. Puleo reaches out and begins telling the reader about the remarkable granddaughter of James Donnaruma, Pamela Donnaruma, the bright, erudite, and lovely publisher and editor of the present renowned paper, the Post Gazette. She has maintained the difficult tradition of never missing an edition. I am taking advantage of this moment to express my personal feelings toward Pam. I am very proud to have her as my friend. What makes me prouder is knowing she considers me to be her friend.

Nineteen pages of Puleo’s Bibliographic Essay give the reader an insight to the amount of research Puleo did to substantiate his outstanding historical document. I believe what makes this book rise above others is Puleo’s unbiased and direct approach to the facts.

As a book critic I give Stephen Puleo’s book, The Boston Italians a five star rating. I strongly recommend that everyone read this masterfully written book.

Lo Specchio

Newsletter of the Italian Geneaological Society of America

Review by Marcia Iannizzi Melnyk, IGSA President

For those who enjoyed Stephen Puleo’s book, Dark Tide, get ready for his newest book, The Boston Italians: A Story of Pride, Perseverance and Paesani, from the Years of the Great Immigration to the Present Day.

This long-awaited book came out in May 2007 and was well worth the wait. This is a must read for all Italian Americans regardless of whether your immigrant ancestors lived in Boston or not. Puleo tells the story of a group of amazing immigrants – our ancestors. His text is engaging, compassionate, and most of all, accurate. He cites many sources for his information without encumbering the story. His grasp of social history, culture and ethnicity – also his ethnicity – is obvious. His chapter on the anarchists and how their actions affected the immigrants was informational. It provided me with many insights into the beliefs and actions of a small handful of Italian immigrants. Our ancestors not only had to overcome the language barrier, discrimination, and poor living conditions but also the negative image of Italians that many Americans held. The majority of Italian immigrants were hard-working, law-abiding residents who were devoted to their family, both in America and in the Italy they left behind.

This story is our story. Puleo has provided us with an inside look at the lives of our grandparents, parents, and even ourselves. We are descendants of an amazing group of immigrants. They may not have been educated or rich but they had a determination, a pride, and a tenacity that overcame so many obstacles. Like us, Puleo has honored our ancestors by telling their story truthfully and with compassion. Thank you Stephen.

Excerpts

(From Chapter 19)

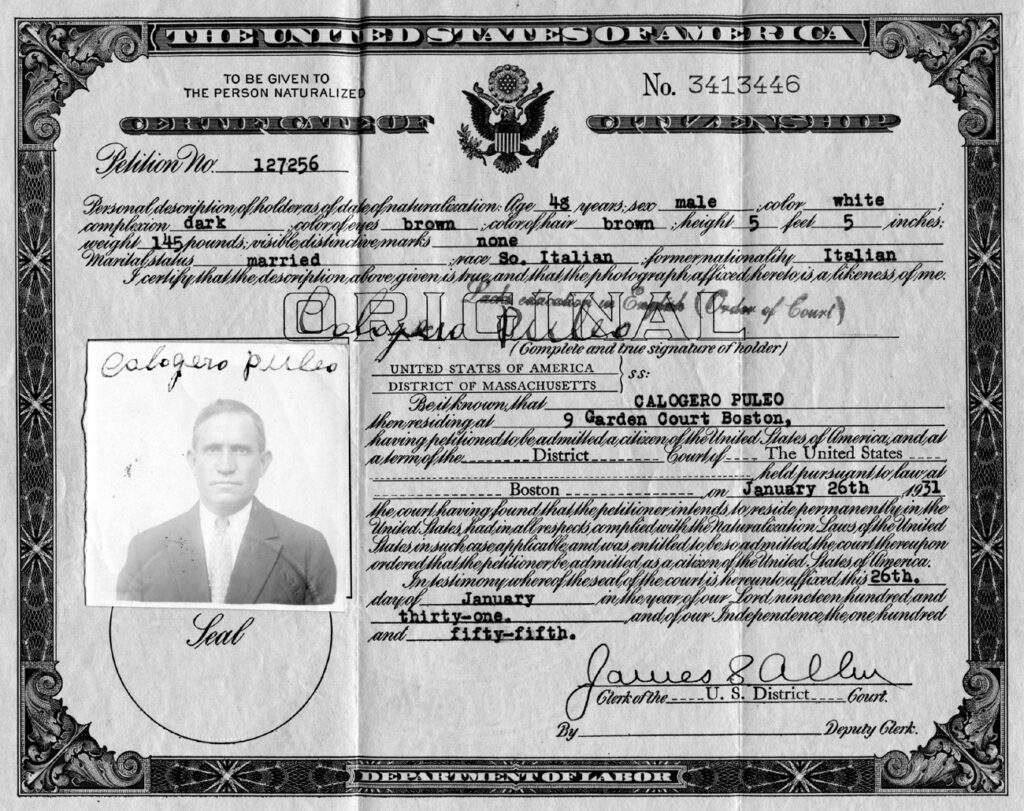

On January 26, 1931, nearly a full quarter-century after he passed through the gates of Ellis Island, my paternal grandfather, Calogero Puleo, became a United States citizen. The 48-year-old fruit dealer, married and the father of ten children, was listed as five-feet, five-inches tall and weighing 145 pounds. His “race” was identified as Southern Italian. A court officer had written “lacks education in English” in purple ink across the Certificate of Citizenship. Two North Endpaesani, Nicola Cesso, a street cleaner, and John Raso, another fruit peddler, served as my grandfather’s witnesses, each swearing that they had known him since 1920. This concluded the citizenship process that he had begun with the filing of his Declaration of Intention in July of 1925, two months after his tenth child, my father, was born.

In the spring of that year, to mark the pride of the occasion, all twelve members of the Puleo family posed for a photo in a studio on Little Prince Street; my father, then six, clutched a small American flag and huddled close to my grandfather, the new citizen.

Also that spring, on May 19, my maternal grandparents, David and Rose Minichiello, celebrated the birth of their second child, another daughter. My mother, Rosina, or Rose, was born six weeks premature in the home her parents rented in Everett, a small city near Boston. But my grandparents’ joy was short-lived and quickly turned to heart-wrenching loss. My mother was a twin, born first; her sister, named Christine after my grandmother’s mother, followed shortly after, struggled for each breath once she arrived in the world, and died less than twenty-four hours after her birth. My mother’s older sister, Mary, then not yet three-years-old, remembered years later Christine’s small white coffin that sat atop my grandmother’s sewing machine table in the brief, but sorrowful, home wake that followed. Neither of my grandparents spoke much of their daughter’s death in the years that followed. It was yet another of life’s hardships to overcome and move beyond.

Angela and Calogero Puleo and David Minichiello had cleared many other hurdles to make America their home: leaving their beloved small towns in Italy, enduring the misery of a transatlantic passage in steerage, suffering the pain of stereotyping and discrimination, engaging in backbreaking labor, carving out a life in an unfamiliar and crowded urban setting. Yet, they and thousands of other Boston Italians also experienced the contentment of sharing their new life withpaesani, the warmth of the neighborhood enclave, the pride in saving money, starting a business, or buying a home.

America was hard, but she offered something Italy never could – the hope, perhaps even the promise, of a better future.

As 1931 drew to a close, the Puleos, the Minichiellos, and all Boston Italians would find their faith in that promise severely tested. If they believed they had survived all the hardships and cleared every hurdle America had placed in their path, they were mistaken.

With little warning or time for preparation, Boston Italians and Americans of all nationalities and geographic regions were about to come face to face with the Great Depression.

Discussion Questions

- In telling the story of the Boston Italians, Steve Puleo weaves in the experiences of his own family. Which member of the Puleo family did you find most interesting? Whose story do you think best illustrated the larger themes of the book?

- The book includes a detailed portrayal of George A. Scigliano, a prominent champion of Italian immigrant causes. In your view, what made him a larger-than-life figure in the eyes of the Italian immigrants? Does he bring to mind any other figures in history who had a similar influence?

- The book also includes a detailed portrayal of James V. Donnaruma, founder of La Gazzetta del Massachusetts. Like Scigliano, he had a profound influence on the lives of Boston’s Italian immigrants. In what ways did his newspaper — and his role as editor — ease Italians’ transition to the United States?

- Immigration is a significant theme in The Boston Italians, including government attempts to place limitations or restrictions on new immigrants. Do you see any parallels with today’s immigration issues? How does today’s situation differ from that of the early 20th century?

- The book describes the “battle” to change the name of Boston’s North Square neighborhood to “Scigliano Square.” Proponents argued it was a fitting way to honor a man who had given so much to the neighborhood. Opponents argued that “North Square,” one of the richest names of Boston in its historic associations, shouldn’t be changed. Would you have been in favor of the name change? Do you think George Scigliano would have been in favor of the name change?

- Prior to reading the book, did you know the reasons why so many Italians chose to emigrate? Were you aware of the difficult conditions they endured in Italy? Were you aware of the magnitude of emigration from Italy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries?

- Based on what you learned about the enormous challenges faced by immigrants, would you have taken the risks involved with seeking a new life in America? Why or why not?

- How well did the book depict the experience of immigrants at Ellis Island? Did you learn anything new by reading about it through the eyes of Italian immigrants?

- Were you aware that Italian-Americans were the victims of lynching, and that they were lynched more frequently than any other group except African-Americans? Why do you think this is such a little-known fact?

- Have you visited Boston’s North End, or an equivalent “Little Italy” in an American city? What was your impression of the neighborhood when you visited? Did The Boston Italians help you see that neighborhood with a new perspective? Would you like to visit again?

- Prior to reading the book, how much, if anything, did you know about violent activities of Italian anarchists in America? What are your thoughts on Sacco and Vanzetti? Were they violent anarchists or simply victims of anti-Italian discrimination?

- In addition to telling the story of the Boston Italians, the book discusses major historical events such as the Great Depression and World War II. Did it help you learn — or learn more — about these events? Did seeing these events through the eyes of Italian immigrants provide new perspective or make the events more interesting?

- The book includes portrayals of today’s influential Boston-area Italians, such as Sal Balsamo, CEO of TAC Worldwide, and politicians Salvatore F. DiMasi, Robert Travaglini, and Tom Menino. Whose story did you find most interesting, and why?

- Did the book change your perception of Italian-Americans? Did the examples of stereotypes in movies and the media raise your awareness of negative portrayals of Italian-Americans? Did it change your opinion about whether these portrayals are humorous?

- If you are of Italian heritage, explain the impact of this book on you personally.

- If you hadn’t been involved with this book club, would you have chosen to read The Boston Italians? Do you typically read non-fiction or history?

- After reading The Boston Italians, do you want to read other books on related topics (Boston history, Italian-Americans, Italian history, anything written by Steve Puleo?)

Buy The Boston Italians

To order The Boston Italians: A Story of Pride, Perseverance and Paesani, from the Years of the Great Immigration to the Present Day, click on a link below.

More

Certificate of citizenship for Steve’s paternal grandfather, Calogero Puleo. He became a citizen in 1931, twenty-five years after his arrival in the United States from Sciacca, Sicily.

The Boston Italians: A “Spiritual Bridge” from Past to Future

Note: This column has been updated since I first wrote it upon the release of the paperback edition of The Boston Italians in 2008

By Stephen Puleo

As the paperback edition of The Boston Italians is released, I wanted to make a few observations about readers’ reactions to the book since the hardcover’s debut a year ago. I have received hundreds of e-mails and spoken to nearly two thousand people at presentations throughout the Boston area

The response has been overwhelmingly positive and heartwarming – from Italian-Americans and others – and has fallen into two main categories.

- First, there is the resounding opinion that the book was long overdue; that it’s simply about time Boston’s second largest ethnic group was the subject of a “non-Mob” book. That the real story – one of Italian immigrants overcoming enormous odds and paving the way for their children and grandchildren to achieve remarkable success – needed to be told.

- The second reaction, surprising to me though equally gratifying, has been the need and desire for Italian-Americans to share their family stories. Virtually every e-mail I receive starts out with, “My grandfather arrived at Ellis Island in 1910” or “My parents raised seven children even though their only income was my what my father earned as a pushcart vendor in Haymarket” or “Mr. Puleo, your story reminded me so much of my own…” It’s as though these readers have wanted to share their stories for a long time but weren’t sure how to do so. The Boston Italians has tapped into that demand and provided the outlet, and I am honored that I had the opportunity to write this story for the first time.

It all goes back to the first generation. More than half the book covers what I colloquially refer to as the Great Immigration and Settlement Years, stretching from the beginning of the Italians’ arrival in Boston up to the onset of the Great Depression. These were the most crucial years of the Italian experience in America, and define to this day how Italian-Americans view their own heritage and how other Americans assess us. The people who defined these first fifty-plus years were the immigrants themselves, who struggled to get to America, overcame hardship once they arrived, contributed their sweat to help build a country, carved a place for themselves and their children in the American mainstream, and forged an ethnic identity that still evokes pride one hundred years later.

As the years go by, and history provides distance and the opportunity for fresh assessment, their sacrifices and accomplishments appear all the more remarkable.

Think about their struggle. Between 1880 and 1921, more than 4.2 million Italians entered the United States, as many as ninety five percent of them through Ellis Island in New York (No other ethnic group during the Great Immigration period sent so many immigrants in such a short time.) Nearly eighty percent of them were from villages and hill towns of Southern Italy and Sicily where they had tilled the land, fished the sea, or worked with their hands, and fled their homeland due to impoverishment; more than half were illiterate, or barely literate, in their own language.

When they arrived in America, some settled in small mining towns or on farms, but the overwhelming majority flocked to America’s large cities and quickly established tight-knit, insular enclaves, Little Italies, like Boston’s North End, which acted as buffer zones of comfort and familiarity in the midst of a strange and hostile urban landscape that was strewn with pitfalls and prejudice.

It was within the cocoon of these enclaves that most Italians settled, purchased property, worshiped, shopped, socialized, and in some cases, worked. It was from these enclaves that Italians ventured out, albeit slowly, to expand their job opportunities, learn English, and finally, assimilate into American culture.

My book looks at Boston Italians within the broader context of the overall Italian experience in America, and that includes why so many left Italy seeking a new life in the first place. More than any other major ethnic group, Italians’ life experiences in the Old Country directly affected their patterns of settlement, manner of living, reliance on family, process of assimilation, and relationship with other Americans.

There’s another reason this book means so much to me, and I think, to readers: the story of the Boston Italians is my story, too.

Three of my four grandparents were immigrants (my maternal grandmother was born in America). My two grandfathers and paternal grandmother arrived virtually penniless, with few skills, and unable to speak English. My paternal grandfather was barely literate in his own language. Both my grandfathers eventually became citizens and entrepreneurs; my grandmother never obtained her citizenship and was even classified as an “enemy alien” at the outset of World War II, despite the fact that three of her sons (including my dad) would eventually fight overseas while serving in the United States Army. My paternal grandparents settled in the North End and stayed for years; my maternal grandfather spent a few years there before moving to the nearby city of Everett. Theirs were the quintessential experiences of Italian immigrants.

My parents and aunts and uncles also shared the experiences of thousands of other children of Italian immigrants. Several of my aunts worked in the garment industry, which was flooded with Italian-American women in Boston. As a young girl, my mother worked in my grandfather’s cobbler shop, lighting the small stove to provide heat in the wintertime and waiting on customers after school, contributing to the family business as thousands of other Italian-American schoolchildren did. My father and two of his brothers served in World War II, which was a defining period for Italian-Americans, one in which they were forced to prove their loyalty to America as the United States battled not just Germany and Japan, but Mussolini’s Italy.

I wove the Puleo story through the course of The Boston Italians because it is illustrative of the overall fabric of the Boston Italian experience, a rich and colorful tapestry of enduring strength and value, one held together for one-hundred-and-thirty years by the legacies of struggle, perseverance, hard work, and the bond of family.

In addition to providing pleasure to readers of all nationalities interested in Boston and immigration history, I hope my book helps continue the resurgence of interest and pride among Italian-Americans, in Boston and elsewhere, in our heritage and our history. One Italian-American journalist said that our appetite to know our ancestors is fueled by our desire to build “a spiritual bridge between [our] Italian past and [our] American future.”

Only with the presence of such a bridge, spanning generations, can we summon their wisdom and example to guide and inspire our own journey.

I hope The Boston Italians provides such a bridge.