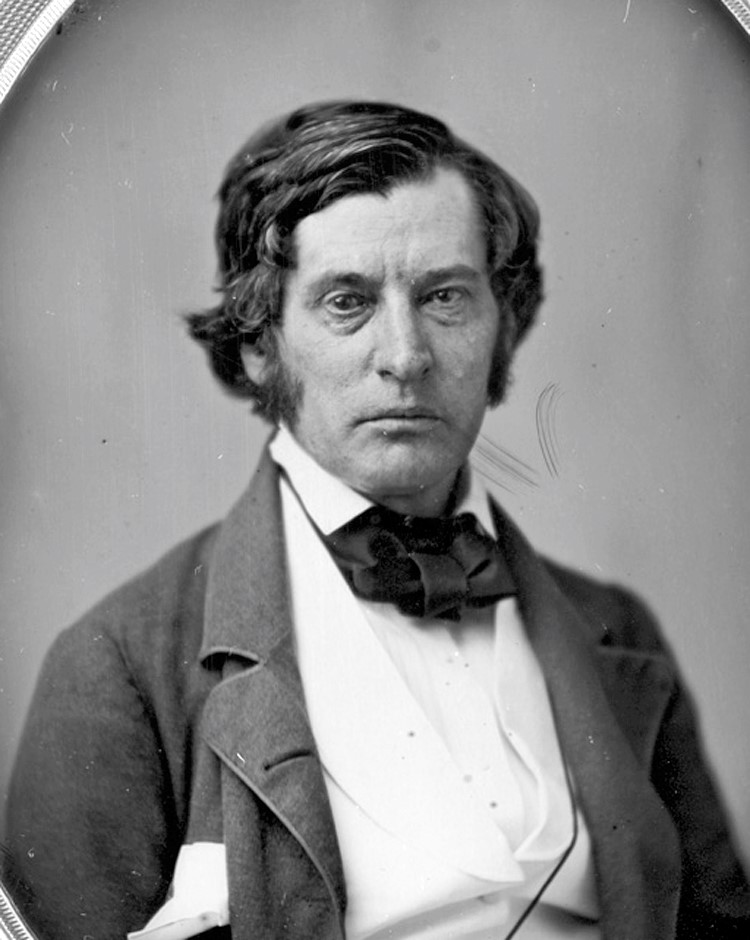

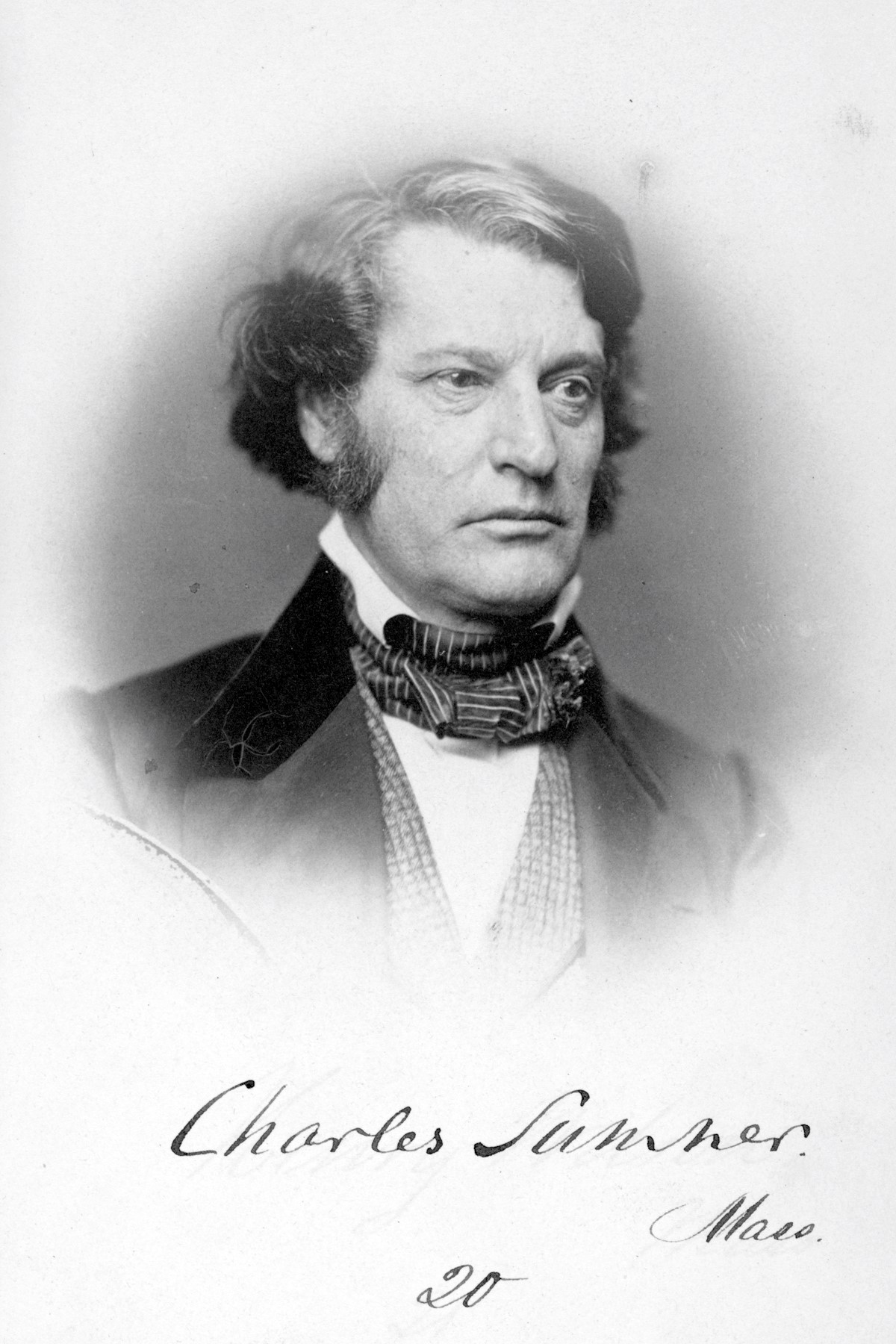

The Great Abolitionist: Charles Sumner and the Fight for a More Perfect Union

THE GREAT ABOLITIONIST: Charles Sumner and the Fight for a More Perfect Union is the first major biography of Charles Sumner to be published in over fifty years. It tells the story of one of the most influential non-presidents in American history (included in this exclusive club were Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Susan B. Anthony, and Martin Luther King, Jr.) – and far more influential than many presidents – a leader who exhibited true courage and authenticity.

In the tempestuous mid-nineteenth century, as slavery consumed congressional debate and America careened toward civil war and split apart – when the very future of the nation hung in the balance – Charles Sumner’s voice rang strongest, bravest, and most unwavering.

Where others preached compromise and moderation, he denounced slavery’s evils to all who would listen and demanded that it be wiped out of existence. More than any other person of his era, he blazed the trail on the country’s long, uneven, and ongoing journey toward realizing its full promise to become a more perfect union.

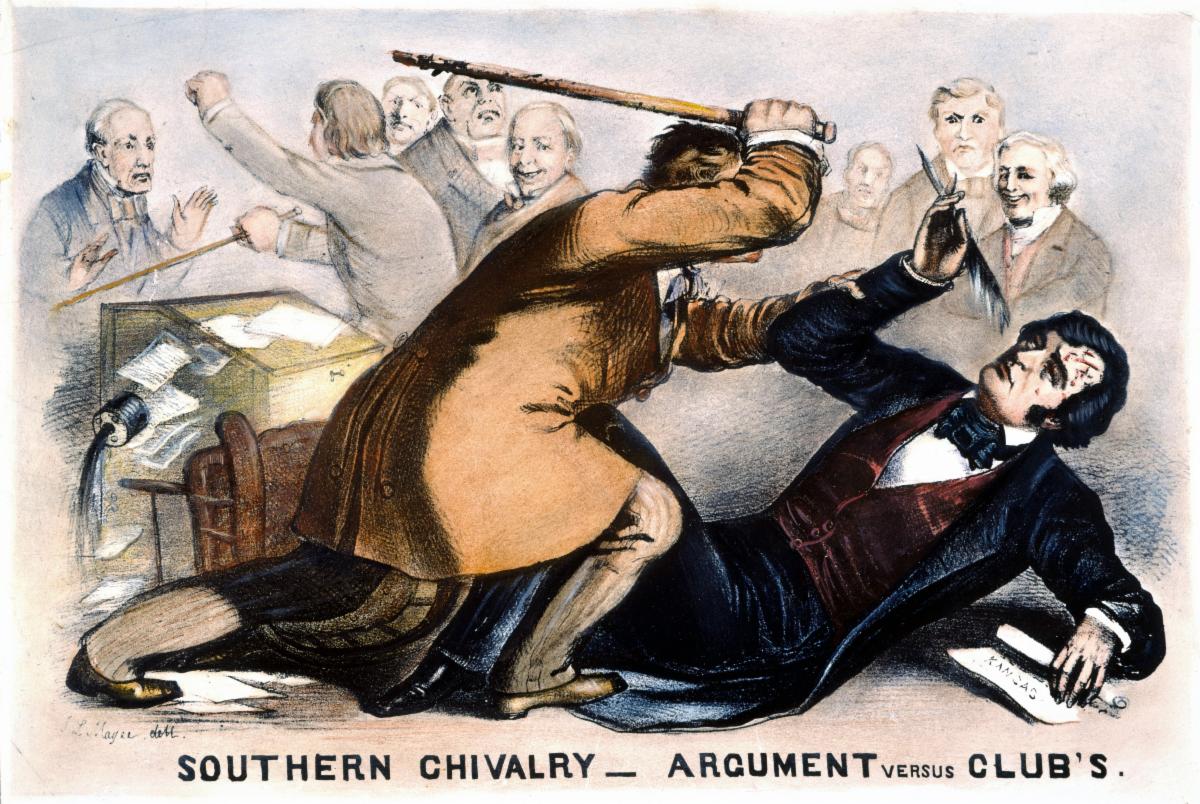

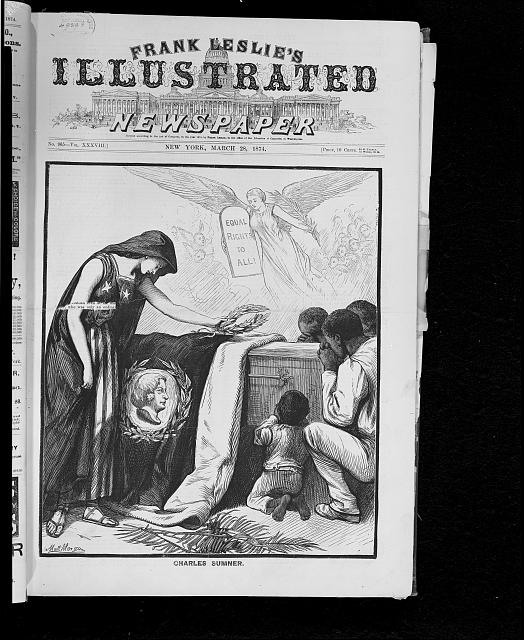

Before and during the Civil War, at great personal sacrifice – which included enduring a vicious beating that nearly killed him – Sumner was the conscience of the North and the most influential politician fighting for abolition. Throughout Reconstruction, no one championed the rights of emancipated people more than he did.

To Sumner, the two concepts of abolitionism and equal rights were inseparable and could not be untethered. Freedom and equality embodied the founding principles of the United States as stated in the Declaration of Independence, and in the Constitution’s guarantee of a republican form of government. Only by enshrining these rights forever could the United States survive.

This view was first considered radical and unworkable, dismissed as the ranting of rabble-rousers on the fringe – positions at first not held even by Lincoln and other anti-slavery Republicans. But Sumner’s influence gradually took hold, permeated the party’s dogma, and finally became the prevalent and official view of Lincoln and the nation.

Through the force of his words and his will, he moved America toward the twin goals of abolitionism and equal rights, which he fought for literally until the day he died. He laid the cornerstone arguments that civil rights advocates would build upon over the next century as the country strove to achieve equality among the races.

Reviews

Reviews for The Great Abolitionist

Kirkus Reviews (“Starred” Review):

(Excerpt) “Puleo’s vast knowledge of 19th-century Boston and its diffident attitude toward slavery and integration—due in no small part to textile merchants and financiers who relied on Southern cotton for their prosperity—adds tremendous value to his account of Sumner’s transformation from depressed and sullen Harvard-educated lawyer to uncompromising and unrelenting civil rights champion, orator, and senator…[The Great Abolitionist is] required reading for anyone with even a slight interest in Civil War–era U.S. history. A wonderfully written book about a true American freedom fighter.”

Publishers Weekly (“Starred Review”)

“Readers won’t be able to get enough of Puleo’s indomitable Sumner.”

Read the full Publishers Weekly review

Harvard Law student and contributing editor, Tom Koenig, wrote a thoughtful and outstanding review for American Purpose magazine. Koenig called The Great Abolitionist a “masterful new biography” of Sumner and really captures the essence of the book in his thorough review. Link to the full American Purpose Review here.

Dennis Lehane, author of Small Mercies: “Stephen Puleo’s masterful account of Charles Sumner, a prickly, conflicted paradox of an American giant, is told with verve and gusto. It’s a vibrant, important story whose echoes still reverberate in our current day. A wonderful read.”

James M. O’Toole, University Historian and Clough Professor of History Emeritus at Boston College: “Charles Sumner, a lifelong crusader for human rights, has not been the subject of a comprehensive biography for more than fifty years. Stephen Puleo fills that gap with this deeply researched and dramatic retelling of Sumner’s courageous life and work.”

William Martin, New York Times bestselling author of The Lincoln Letter and December ’41: “Sometimes, a giant needs a little help. He passes through history, leaving huge footprints that are filled by time and covered over by events. Well, in Stephen Puleo’s superb new biography, Massachusetts Abolitionist Charles Sumner gets all the help he needs. In prose that is perceptive and propulsive, in scenes that are powerful and dramatic, Puleo brings Sumner vividly to life. Once more, The Great Abolitionist drives the momentous events of the mid-Nineteenth Century. Once more, the strength of his character, the intensity of his personality, and the honor of his crusade shine before us. And once more, Stephen Puleo delivers a book that will captivate the general reader and reward the serious historian, too.”

Gregg Olsen, New York Times and Amazon Charts bestselling author of The Amish Wife and If You Tell: “When it comes to impeccable research – the kind that surprises and never rehashes – no one does it better than Stephen Puleo. The Great Abolitionist is a literary and historical triumph and is sure to be on many year-end “best” lists in 2024.”

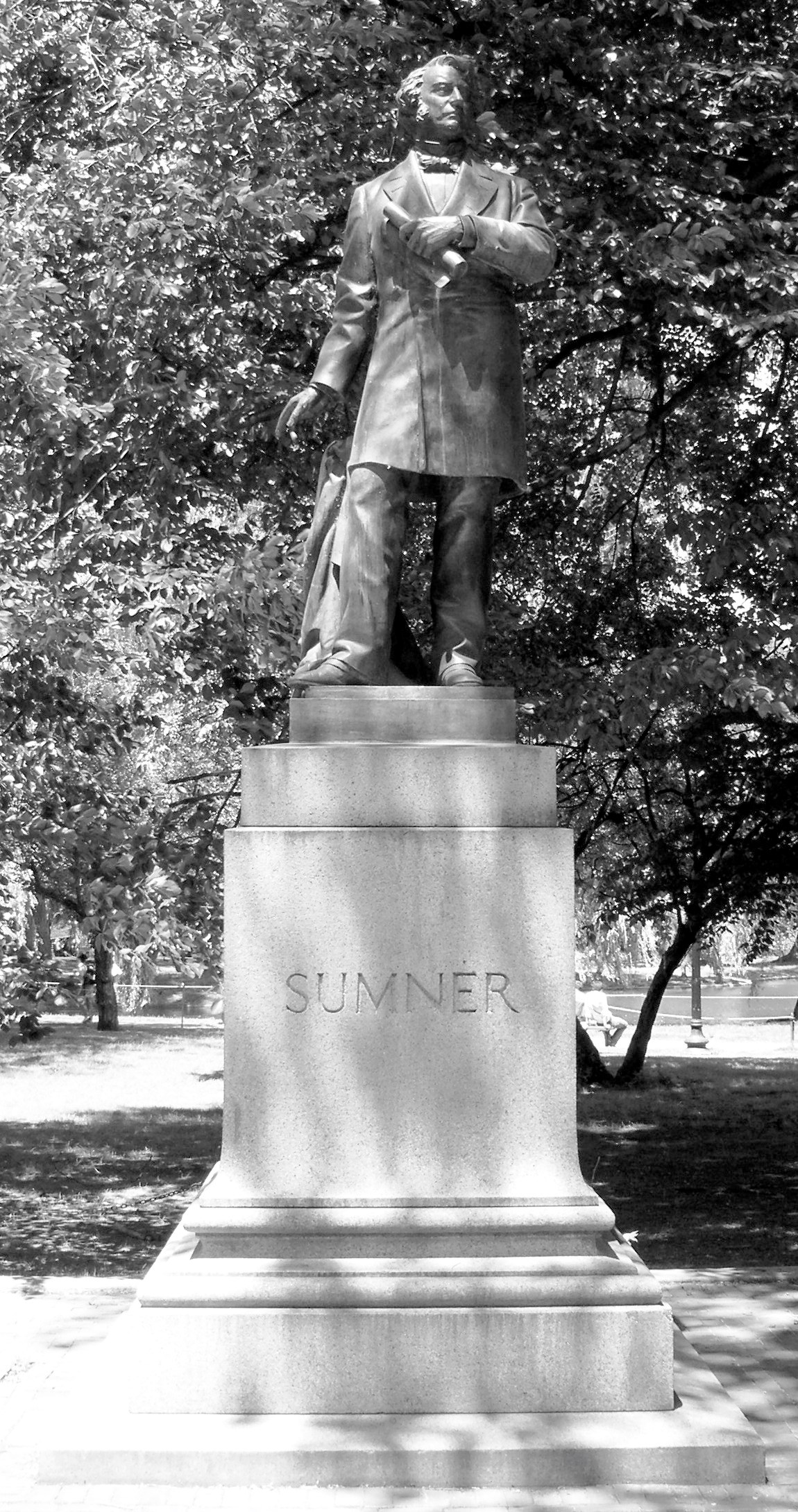

William J. Kole, veteran journalist, author of THE BIG 100: The New World of Super-Aging: “Nearly two centuries on, Charles Sumner’s name still drops loudly in Boston, yet few appreciate the enormity of his impact. Stephen Puleo’s The Great Abolitionist is at once a revelation and an appeal to our better angels to heed the lessons Sumner’s example can teach us.”

Eric Jay Dolin, author of Left for Dead and Black Flags, Blue Waters: “Charles Sumner was a principled man of unshakable conviction, who fought the good, noble, and heroic fight against slavery, and he deserves to be remembered as a great statesman and one of the foremost champions of civil rights. He also deserves a compelling and wonderfully-written biography, which is what Stephen Puleo has provided.”

Christopher C. Gorham, author of THE CONFIDANTE: The Untold Story of the Woman Who Helped Win WWII and Shape Modern America: “In THE GREAT ABOLITIONIST we feel the cold wind in the cobbled streets of mid -19th century Boston and hear the stifled sobs at Abraham Lincoln’s deathbed in April 1865. The subject of Stephen Puleo’s eighth book is Charles Sumner, a lawyer and U.S. Senator who was a leading voice of antislavery during the tumultuous two decades before the Civil War. As the nation was adding Texas, rushing west for gold, and vainly seeking a compromise on slavery to avoid war, Puleo paints Sumner’s morality as a constant. We are in the courtroom as he argues against the inherent inequality of segregated schools (a century before Brown v. Board of Education), and the drawing room as Sumner persuades the sixteenth president to publicly stand for abolition. Sumner’s ideals cost him friendships and resulted in a bloody assault on the floor of the senate by a pro-slavery congressman. Puleo’s rich biographical history is a perfectly timed reminder that to survive, our union needs figures with the courage to stand for core ideals which cannot be compromised.”

Excerpts

Three Excerpts follow from The Great Abolitionist…

Excerpt 1 – From the Prologue:

Charles Sumner was the boldest, most controversial, and most influential voice of America’s most turbulent two decades: the 1850s and 1860s. No one else came close.

As great events played out across the land during this period, Sumner seized the national narrative, refused to let go, and repeatedly held a mirror up to the country’s aspirations and ideals. He inspired those who agreed with him, swayed fence-sitters, and eventually converted millions of naysayers. He had a particular understanding of the power of words and big themes to move people, to challenge their ways of doing things.

It was Charles Sumner who first used the phrase “equality before the law” in the United States, who first argued that “separate but equal” violated the precepts of the Declaration of Independence, and who infused the concept of “equal protection” for all into the language of the Fourteenth Amendment.

His oratory was his gift, if occasionally his undoing. He never backed down, never tempered his remarks, never prevaricated. Throughout his career, he was responsible for passing almost no significant legislation (though as a legislator, he is often underrated), and yet for two decades, in an era when senators often wielded more power than presidents, he was the most powerful man in the U.S. Senate.

Sumner understood politics, but he had little patience for the political process or in nourishing personal relationships that made the process run smoothly. Yet, merely uttering the words “U.S. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts” was enough to stop both his allies and his enemies in their tracks. Supporters trumpeted his courage, his resilience, and his moral certitude. Detractors detested his arrogance, his seeming lack of empathy, and his utter contempt for those who disagreed with him.

But without question, when Charles Sumner spoke, everyone listened.

_______

Like Winston Churchill during World War II and Martin Luther King, Jr., during the civil rights era, Charles Sumner, throughout the 1850s and 1860s, relied most heavily on the uncompromising clarity of his ideas, his relentless honesty, and his steadfastness as his most effective attributes as he sought to move the heart and mind of a country embroiled in crisis. Like Churchill and King, too, he employed rhetoric befitting big moments, and like both twentieth-century leaders, he shaped—and was shaped by—grand causes and occurrences.

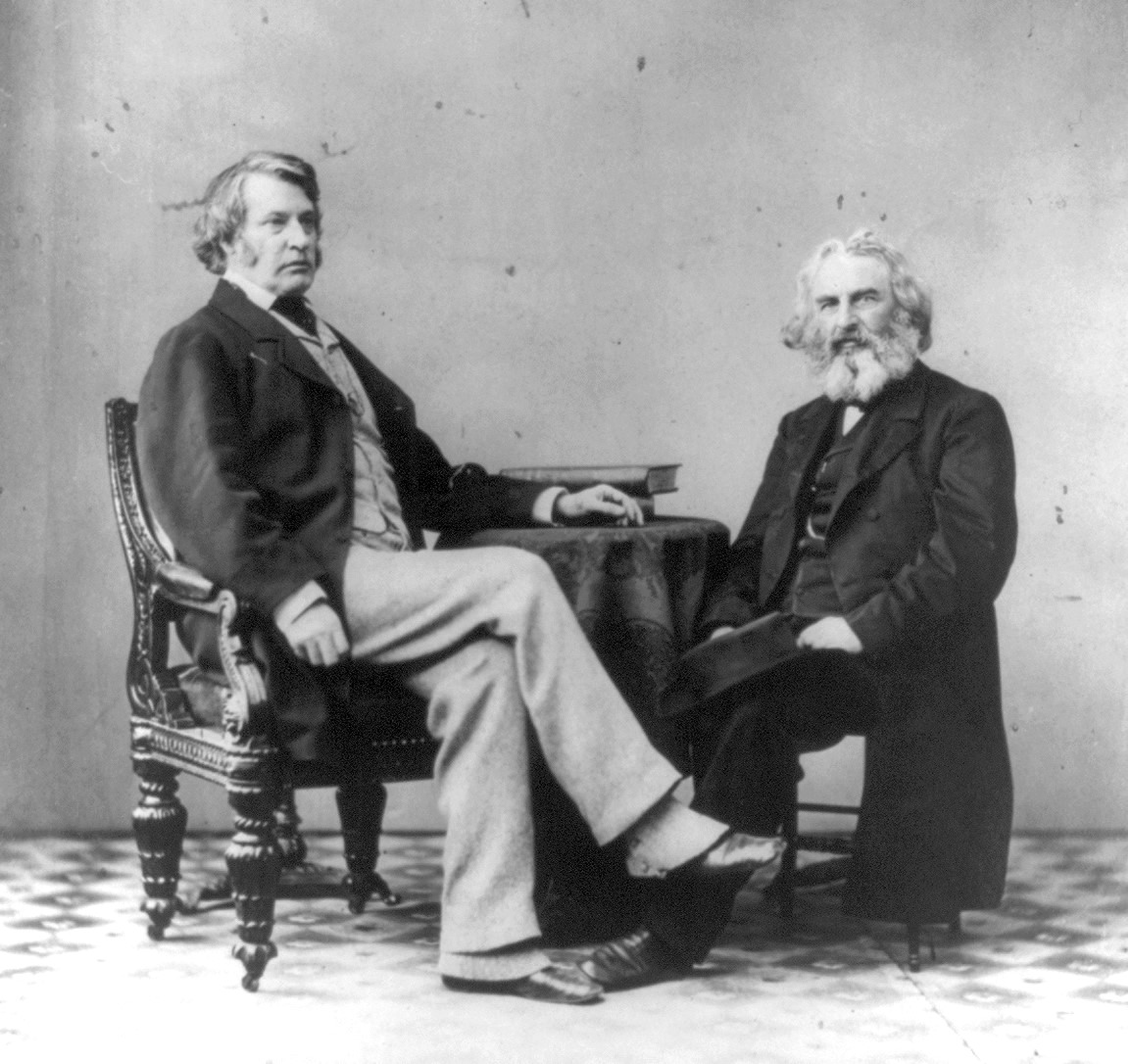

He knew instinctively what was at stake and how to convey it. “The great hours of history seem to be tolling now,” he wrote to his dear friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1859, understanding fully and capturing the gravity of deteriorating relations between North and South. After Lincoln’s election in 1860, when it was clear that Southern states would secede and the union would break apart, Sumner recognized the momentousness of the occasion and reminded Longfellow that, even in the midst of such dire crisis, faintheartedness was not an option.

“There must be no yielding on our part,” he said. “We are on the eve of great events.”

______

Throughout his lifetime, in countless compelling moments, Charles Sumner’s eloquence and inexhaustible zeal would shape the debate and ignite the passions of a nation.

No single individual did more to influence the antislavery movement on a national scale. No single person was more responsible for founding and fueling the growth of the antislavery Republican Party. No single lawmaker advocated for such broad and sweeping equal rights for African Americans or fought to make the discussion of such rights a reasonable and respectable option for their congressional colleagues.

His positions cost him dearly. Southerners despised him, sometimes feared him, and celebrated gleefully when Sumner was beaten unconscious in the Senate chamber. Northerners initially blanched at his abolitionism, later resisted his demands for equal rights as detrimental to the nation’s attempts to heal, and often found his chafing personality off- putting.

But most came to respect him and his positions, and near the end of his life, they elevated Sumner to revered elder-statesman status. His political courage and moral clarity established him as the national conscience on the issues of slavery and equal rights.

More than any other person of his era, perhaps of any era, Charles Sumner blazed the trail on the country’s long, uneven, and ongoing journey toward realizing its full promise, its ever-striving quest to become a more perfect union.

Excerpt 2 – After Sumner’s strenuous opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act

September 7, 1854, Worcester, Massachusetts

The crowd of several thousand murmured at first, then craned their necks as one, searching for Charles Sumner and then, finally, spotting him as he made his way into the great hall. Suddenly, the immense audience rose in unison, stomped their feet, and cheered wildly — “Sumner! Sumner! Sumner!” they roared—as the tall senator passed by on his way to the speaker’s platform. The thunderous ovation continued for several minutes as men waved their hats frantically, whooped, and thrust their fists skyward.

They had come specifically to see Sumner, to hear his voice, to let him know they appreciated his toughness, and attendees swore later that never had a crowd delivered such an enthusiastic response to a public speaker. Never either, in the words of one writer on the scene, had Sumner “been so near the heart of Massachusetts as then.”

The occasion was the nominating convention of the new Republican Party—a patchwork antislavery coalition of former Free Soilers, Whigs, and even some Democrats—whose Massachusetts leaders begged Sumner to attend to ensure a large, boisterous, and enthusiastic audience.

Sumner stepped to the rostrum, and the cheers and shouts grew louder. He raised his hands and waited for the furor to subside before speaking. And when he did, the crowd responded. Sumner’s voice was powerful in volume, earnest in pitch, and indignant in tone. He had two objectives for the speech—to “vindicate the necessity of the Republican Party,” and to destroy the Fugitive Slave Law operation in Massachusetts.

His ninety-minute speech was interrupted every few moments—and in some parts at the end of each sentence—by loud and prolonged applause from the appreciative audience.

Sumner blasted the national proslavery administration, branded the Kansas-Nebraska Act an atrocity, and said federal authorities had shamelessly run roughshod over the law, and over Boston, in the Burns case. He viewed this new, principled Republican Party, fledgling though it was, as the only antidote to the slave power, arguing that neither Democrats nor Whigs could effectively carry on the fight. The Whigs were split irreparably over the slavery question, and the Democrats had maintained commercial and policy alliances with slaveholders for so long that it was fanciful and naïve to expect them to bite the hand that fed their political interests.

The Republicans were the nation’s best hope—maybe its only hope—to end the scourge of slavery, and what the party lacked in numbers and political clout it made up for in enthusiasm and vision.

_______

Sumner had returned home from Washington “full of fight on the slavery question” and rejoiced after the response he received in Worcester.

His popularity had grown so much that journalists, even unfriendly ones, could not afford to ignore him. One newspaper, the Traveller, hired a special train from Worcester so it could publish Sumner’s speech for its Boston readers, forty miles away, the same afternoon in advance of its rivals. Even the most ardent Whig journals acknowledged Sumner’s impact on the audience. Sumner noticed it, too. “The change towards me is rather with the great bulk of the people than with the old leaders,” Sumner observed with satisfaction. “It is apparent wherever I go—in the streets and also in the newspapers. No papers in Massachusetts now mention my name except with kind words.”

After the Worcester response, the Massachusetts Republican state committee distributed Sumner’s speech widely in pamphlet edition. He instantly became the new party’s public face. Sumner would eventually and almost single-handedly be responsible for the meteoric growth of the Republicans on a national scale, though, as the calendar turned to 1855, neither he nor anyone else could ever have imagined how.

For the rest of the year and into 1856, the great slavery debate shifted away from Massachusetts, away from Washington, D.C., and the plantations and capitals of the Deep South.

Instead, thousands of eyes were cast westward.

Assaults, barbarity, crime, mayhem, and sectional strife were sweeping the Great Plains.

Kansas was bleeding.

Excerpt 3 – March – June 1864, after repeal of all Fugitive Slave Acts

Even after the Senate had passed the Thirteenth Amendment and sent it to the House, Charles Sumner refused to rest. More than anything or anyone else over the previous two decades, his voice and his work had brought the Senate—and by extension, the country—to this point. Now, on the intertwined issues of slavery and equality, he wished more.

Since he had delivered his first major speech in the Senate twelve years earlier, a blistering attack on the Fugitive Slave Law, Sumner had envisioned a day when this most odious component of the Compromise of 1850 was forever stricken from U.S. law, along with its less harsh 1793 counterpart. Now, with the Thirteenth Amendment fresh in the minds and hearts of his colleagues, Sumner, during a stirring April 19, 1864, speech, said that it was time “to remove this shame from our statute-book.”

If the Thirteenth Amendment ultimately secured passage in the House and ratification in the Senate, the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Laws would largely be academic and symbolic—if slavery was abolished, there could hardly be any fugitives from slavery.

But congressional repeal of the fugitive laws was one of his insurance policies, the practical legislative manifestation of his philosophical pledge to strike against slavery any chance he could.

He met resistance from some senators who were content to repeal the 1850 law but balked at eliminating the 1793 act because it was crafted by the “men who framed the Constitution” and declared valid and constitutional by every tribunal since. The eighteenth-century law was seldom enforced and thus hardly onerous; by repealing the 1850 law and retaining the 1793 act, could not the Senate accomplish its goals while showing appropriate reverence for the Framers?

No, Sumner replied in his speech — “the argument against one is the same against all.” He answered objectors by challenging them to look at the sacrifices made by colored Union troops at Fort Wagner and at the grisly massacre of black officers and soldiers at Fort Pillow. How could they possibly draw distinctions between the severity of the two laws?

As April dragged into May and then June, Sumner continued to meet opposition and battle through it. Inspired by his arguments, the House of Representatives passed its own resolution calling for the repeal of both Fugitive Slave laws and sent it over to the Senate. The Senate delayed it for another week, and when Sumner brought it up again on June 22, exasperated border-state senator Willard Saulsbury of Delaware demanded the Senate adjourn without a vote. “Let us have one day without the nig- ger,” he begged, a sentiment shared by many slaveholding border-state lawmakers who continued to fear that abolitionists would turn against them next, regardless of their importance to the war effort.

Saulsbury’s motion failed, and the Senate haggled late into the night. Sumner pressed for a vote—but as close as he was to success, tempers were frayed and members exhausted. Sumner received some aid from Ohio Republican John Sherman, who decried parliamentary delays and declared that he was “perfectly willing now to go into a contest of physical endurance” to pass the bill.

But deep into the night, the Senate adjourned one more time.

_______

Finally, on June 23, after beating back additional efforts by border-state senators to omit the Founder-drafted 1793 bill from the legislation, the Senate voted, finally, to repeal all Fugitive Slave Acts.

President Lincoln would sign the bill into law on June 28, 1864. Sumner could not wait to let Longfellow know of the Senate’s action.

Noting in his letter that he was writing from the Senate chamber at “10 minutes before 4 o’clk p.m.” on the twenty-third, Sumner dashed off a short message: “My dear Longfellow—All fugitive slave acts were to-day expunged from the statute-book. This makes me happy.” He signed it, “Ever Thine, Charles Sumner.”

And then Sumner added a postscript: “Thus closes one chapter of my life. I was chosen to the Senate in order to do this work.”

Discussion Questions

Charles Sumner is credited with being the first to use the phrase “equality before the law.” Why is that significant to note? How does he infuse equality into the Fourteenth Amendment?

What was Sumner’s relationships with other abolitionists? What about his relationship to women’s abolitionists? How did Sumner feel about women’s rights? Was equality just for native born men or did it also include native born women? What about foreign-born men and women?

How would you have reacted after learning of Sumner’s assault on the floor of the Senate if you were a resident of Massachusetts? How would you have reacted if you were a supporter of Preston Brooks residing in the South?

How would Charles Sumner describe himself? Did he fashion himself a bold political reformer or more a man of conviction? What events led you to choose a description?

How would you describe the relationships Charles Sumner had with his peers, constituents, friends, and spouse? Did they influence his abolitionist ideas and political ambitions? Did his dour demeanor work for or against him?

Were you surprised to learn of Sumner’s friendship with President Lincoln? Did their differing personalities enhance or diminish their ability to work together? How did their friendship affect strategic policy making?

After Lincoln’s assassination, what was Sumner’s influence on the process of Reconstruction? How did he promote an end to government discrimination? What would he think about the approach the modern US government takes to equal rights legislation?

In current discussions about civil rights leaders, how prominently should Charles Sumner’s name be mentioned? How did he make his message of equal rights heard?

Were you surprised that the Founding Fathers’ views on slavery had a substantial influence on Sumner? How did the documents that they created, most notably the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, significantly impact Sumner’s tactics as he fought against slavery and in favor of equal rights?

Have you read other books by Stephen Puleo? If so, how does The Great Abolitionist compare in terms of writing quality and storytelling? Do you agree with Puleo’s description of this narrative as a “biographical history”? If this is your first Puleo book, would you be inclined to read another?

Buy The Great Abolitionist

Put The Great Abolitionist on your Goodreads “Want To Read”

More

History Happy Hour Episode 203: Abolitionist Charles Sumner

Hosts Chris Anderson and Rick Beyer welcomed Steve to talk about The Great Abolitionist. Catch Steve’s interview, and ongoing episodes airing on Sundays at 4:00 pm ET, at History Happy Hour, where history is always on tap.

Boston.com Book Club presents 4 takeaways from The Great Abolitionist discussion

Read the article here.

The History Reader

Visit The History Reader website, where you can read a column I wrote about the Charles Sumner – Abraham Lincoln relationship, entitled Charles Sumner Witnesses the “Abraham Lincoln Magic.”

Why I’m Calling The Great Abolitionist a “Biographical History”

By Stephen Puleo

For me, The Great Abolitionist is a first – my first biography! And actually, I’m calling it a “biographical history,” since Charles Sumner’s life encompassed the life of the nation during the 1850 and 1860s, and into the 1870s. He stood tall and ramrod straight at the center of events that millions of Americans would experience in his era, and then learn and study for 175 years (and counting).

This complex man was a force for nearly a quarter-century including twenty-three consecutive years in the Senate from 1851 until his death (which encompassed a three-year absence as he recovered from his caning injuries). During this time, it was Charles Sumner – not Lincoln, not William Lloyd Garrison, not Frederick Douglass, Lydia Maria Child, or anyone else – who was the nation’s most passionate, vociferous, unrelenting, and inexhaustible anti-slavery and equal rights champion.

His contributions were everywhere: his unrelenting efforts to abolish slavery and fulfill the nation’s promise of civil, political, and racial equality; his expertise in foreign affairs that helped the United States avoid a potentially devastating war with England even as the country battled the Confederacy; his close working relationship with President Abraham Lincoln (Sumner was at Lincoln’s bedside the night the President was assassinated); and his influence upon virtually every major debate and issue that the country tackled in the decade prior to the Civil War, the war itself, and during Reconstruction.

These included the Fugitive Slave Law; the Kansas-Nebraska Act; the battle for the soul of Kansas that became a symbol of abolitionist and pro-slavery tensions; the founding of the Republican Party; Lincoln’s election in 1860; the secession of Southern states; as head of the Radical Republicans throughout the war; the Trent Affair in which Sumner was the primary force in averting war with England; the Emancipation Proclamation, which he repeatedly beseeched Lincoln to issue and whose language he helped shape; Lincoln’s remarkable and unexpected re-election in 1864; the President’s assassination; the crafting of Reconstruction policy; the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson; the Reconstruction amendments; as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during the administration of Ulysses S. Grant; and as the architect of a proposed sweeping civil rights bill that called for an end to all government and private sector discrimination.

As the nation literally fought for its life, Charles Sumner influenced, altered, and often defined America’s course – in the moment and for the future. In the face of repeated insults, ridicule, personal setbacks, and a devastating physical attack, Charles Sumner’s voice and his ideas moved a nation, slowly, even grudgingly at first, but eventually with a surety that accompanies righteousness.

For Charles Sumner, freedom and equality were America’s national birthright, and slavery and racist laws were a perversion of those ideals. He saw the government’s tolerance and support for the growth of slavery as an ignorant misreading of the country’s founding documents, not an inevitable condition flowing from them.

In the end, Charles Sumner truly believed in America. He believed in it as he held up a mirror to its flaws and challenged the country to live up to its ideals. He believed in it as he ferociously battled slavery and inequality. He believed in it as he endured and recovered from a vicious beating for speaking his mind. As one Congressional eulogist declared, Sumner “believed in his country, in her unity, her grandeur, her ideas, and her destiny.”

Dour and disconsolate as he often appeared, he was an idealist at heart. He told all who would listen that his often lonely fight to create a more perfect union was a burden well worth shouldering – that the fulfilled promise of America could literally change the world.

If you’ve enjoyed my other work, I’m confident that you’ll enjoy The Great Abolitionist, too. You’ll find that it is sweeping in its scope, but rather than focusing on Sumner’s every movement and utterance between childhood and death, this “biographical history” traces the arc of his antislavery and equal rights leadership as he stood at the center of the storm that swept across the nation during the 1850s and 1860s.

From the moment Charles Sumner stepped onto the public stage, he made his fight America’s fight. I’ve tried to tell the story — Sumner’s story, the nation’s story — with the same fast-paced narrative style and an exciting story arc that you’ve become accustomed to in my previous books.