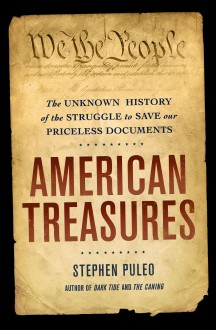

American Treasures

The Secret Efforts to Save the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Gettysburg Address.

On December 26, 1941, Secret Service Agent Harry E. Neal stood on a platform at Washington’s Union Station, watching a train chug off into the dark and feeling at once relieved and inexorably anxious. These were dire times. Hitler’s armies were plowing across Europe, seizing or destroying the Continent’s historic artifacts at will, and three weeks earlier Japan unleashed its devastating attack on Pearl Harbor. American officials now feared an enemy attack on Washington, D.C.

So, President Franklin D. Roosevelt set about hiding the country’s valuables. On the train speeding away from Neal sat four plain-wrapped cases containing the documentary history of America – including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Gettysburg Address – guarded by a battery of agents and bound for safekeeping in the nation’s most impenetrable hiding place.

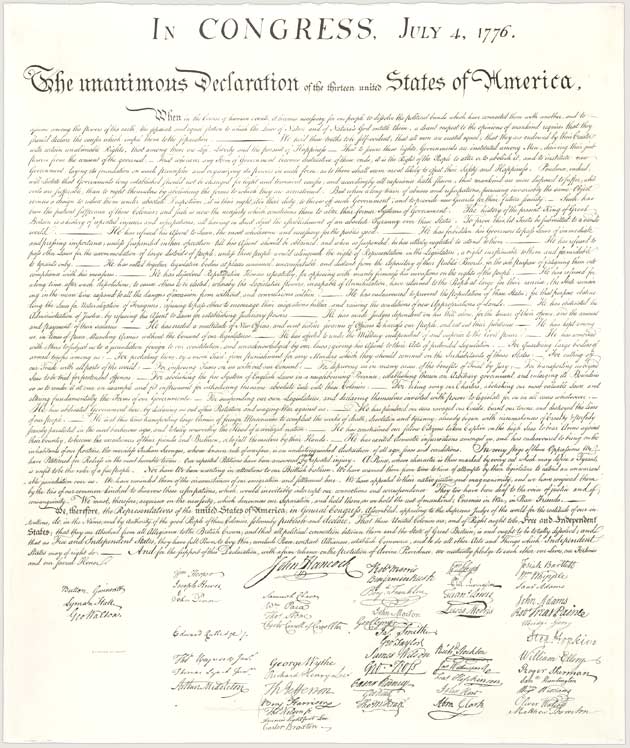

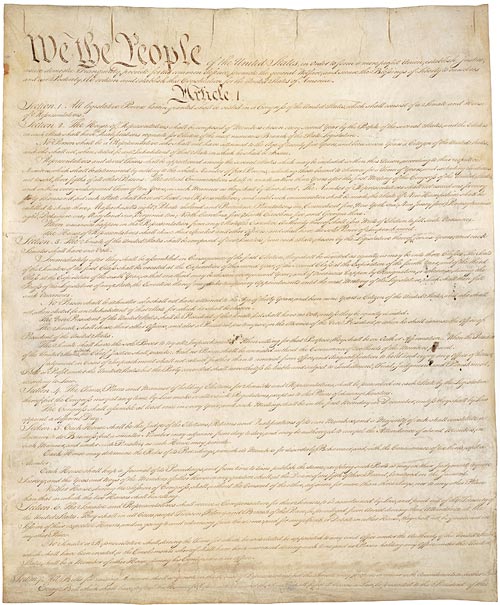

American Treasures charts the creation and little-known journeys of these priceless American documents. From the risky and audacious adoption of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 to our modern Fourth of July celebrations, shows how the ideas captured in these documents underscore the nation’s strengths and hopes, and embody its fundamental values of liberty and equality.

Stephen Puleo weaves exciting stories of freedom under fire—from the smuggling of the Declaration and Constitution out of Washington days before the British burned the capital in 1814, to their covert relocation during WWII—crafting a sweeping history of a nation united to preserve its democracy and the values embodied in its founding documents.

Reviews

David S. Ferriero, Archivist of the United States:

“Stephen Puleo once again educates, enlightens, and entertains us, this time through the history of the most important documents of our democracy. A tour de force based on exhaustive research into both primary and secondary sources, he tells the miraculous stories of the survival of the most precious evidence of our freedom thanks to, until now, the unsung heroes and heroines of our past.”

Richard R. Beeman, Author of Plain Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution:

“Stephen Puleo has written an extraordinary and truly innovative book on a subject on which hundreds of books have been written: the great American documents, most important among them the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution and the Gettysburg Address. Puleo weaves together the fascinating story of how the documents were created, how they came to be protected in times of national crisis, and how as a result they have become ever more priceless.”

William Martin, New York Times Bestselling Author of The Lost Constitution and The Lincoln Letter:

If you yearn for a book that sweeps you through time, forging fresh new connections between past and present while reinforcing universal truths about our national aspirations, read American Treasures. It’s a rich and resonant narrative history, surging with character and incident, the kind of book that you will devour for the depth and breadth of its erudition and, more simply, because it’s a terrific tale, told by a fine historian who also happens to write like a seasoned novelist.

Doug Most, Author of The Race Underground: Boston, New York, and the Incredible Rivalry That Built America’s First Subway:

“There are not many secrets left in our country’s storied history, and here Stephen Puleo has uncovered a true gem. American Treasures takes readers on an incredible journey filled with mystery and surprise. American Treasures is an American treasure.”

Kenneth C. Davis, Author Don’t Know Much About History, America’s Hidden History:

“Weaving together a riveting narrative of the effort to keep America’s founding documents safe from harm during World War II with a stirring recap of the origins of the Declaration, Constitution and other precious American treasures, this is a wonderful tale. Not only does Stephen Puleo recount the little-known heroics of Archibald MacLeish, the Librarian Congress, in a post Pearl Harbor climate of fear, he also reminds us of how these “Charters of Freedom” are what truly make America exceptional.”

Library Journal:

“An engrossing account of the creation, consecration, and conservation of the documents that defined American democracy. Readers will take away a new appreciation for the vision and savvy of government officials in finding ways to ensure such treasures would survive.”

Kirkus Reviews:

A novel perspective on American history that focuses on the story of the country’s founding documents and the Americans who composed, safeguarded, and preserved them for the benefit of future generations.

American History magazine contributor Puleo concentrates not on the drafting of the Declaration of Independence and other documents but rather their preservation. Near the beginning of World War II, Franklin Roosevelt had requested that Archibald MacLeish, Librarian of Congress, prepare a plan to safeguard the nation’s key founding documents. He feared that Hitler would bomb the capital city. MacLeish had to select the documents to protect as well as safe storage sites. That endeavor provides Puleo with a unique frame for a recounting of the history of the physical documents and their continued existence as well as the revered history of their creation. The author’s fast-moving presentation combines the familiar stories of their adoption and passage with those of their subsequent production and dissemination. The Declaration of Independence passed on July 2, not July 4, and the official signing didn’t take place until a month later. Only after four more months did all the names appear on the copy held by the printer. The author makes it clear not only how dangerous it was to be associated with those awe-inspiring documents, but also how threatened they were. Without the courageous initiative of Dolly Madison, for example, it is doubtful the treasures could have been saved from destruction in the fires set by the British during the War of 1812. The drafting and circumstances of delivery of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address helps round out the picture. In addition to threats, anniversaries and celebrations continue to call forth efforts to preserve and protect these precious documents from enemies and the passage of time.

A solid retelling of an inspiring story.

The Patriot Ledger

By Jody Feinberg

Even trivia buffs may be surprised by this July 4 fact. The Declaration of Independence once was locked among the gold in Fort Knox, after the United States U.S. government secretly moved it and other founding documents from the Library of Congress. Fearful of an attack on Washington, D.C., after Pearl Harbor, the government also packed 5,000 boxes of historical papers into vans headed for university libraries.

The story of these extraordinary protection efforts is told in the book “American Treasures: The Secret Efforts to Save the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Gettysburg Address,” which will be published August Aug. 30.

“I felt like I knew a lot about World War II, but had never heard of this,” said author Stephen Puleo of Weymouth, whose interest began after he came across a brief mention. “I wanted to understand this herculean effort.”

After the United States entered World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt, Library of Congress director Archibald MacLeish, the director of the Library of Congress, and Harry Neal, a top aide to the chief of the Secret Service, were determined to be proactive to protect these treasured documents. On Dec. 26, 1941, “four wrapped packages” traveled by overnight train and were locked the next day inside Fort Knox, Kentucky. The transfer of the 5,000 boxes of documents to the University of Virginia, Washington and Lee University and Denison College took place over about two months, packed into about 29 vans.

Remarkably, the moves remained secret until after the war, something Puleo suspects could not happen today.

To tell the story, Puleo researched not just the events of 1941 and 1942, but the creation of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Gettysburg Address, all now housed in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. His vivid and detailed descriptions of characters and events will make readers feel like they are in the room with historic figures.

“It became clear that the story really was about the documents themselves, what they meant to people and their motivations for protecting them,” said Puleo, author of five other history books. “No one else has told the story of the protection of the country’s big three documents as part of the overall story of American history.”

At this time of year, Puleo thinks more frequently about the Declaration of Independence. He will celebrate the day with his wife, Kate, principal of St. Jerome School in North Weymouth, and friends in New Hampshire.

“I’m a bit of a history evangelist,” said Puleo, who followed his passion at age 40 and earned a master’s degree in history at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

Over the four years Puleo researched and wrote “American Treasures,” he worked in public relations and communication for a health care company and taught at Suffolk University. Like “American Treasures,” his previous book “The Caning” examined the significance of a single event in the context of the nation’s broader history.

“I love the research and writing and speaking to audiences and meeting readers,” Puleo said. “I hope readers understand that these documents define us and are interwoven with the promise of America. In an age of cynicism, they remind us of that promise.”

Excerpts

FDR Secures the Declaration of Independence, May 13, 1942

May 13, 1942, Securing the Declaration of Independence at the U.S. Bullion Depository, Fort Knox, 3:30 p.m.

Under the watchful eyes of Verner Clapp and two restoration experts from Harvard, guards carried the case containing the Declaration of Independence from the vault to the north room, which had been set up as a work area. Clapp inspected the case’s seals and locks and found them all intact.

For the next hour, parchment expert Dr. George L. Stout of Harvard, and his assistant, Evelyn Ehrlich, prepared to undertake restorative work on the Declaration of Independence. They had traveled to Kentucky, in secret and at Clapp’s request, in order to assess the impact of storage in Fort Knox on the document. Stout was one of the country’s foremost experts on art conservation and restoration—he would later become one of the famous Monuments Men who traveled to Europe to retrieve and protect art treasures stolen by the Nazis.

Stout and Ehrlich spent the late afternoon opening the wooden case and preparing to open the bronze container that contained the Declaration of Independence. They unpacked their tools and supplies and laid them out carefully. Then they thoroughly vacuumed the room and recorded atmospheric conditions. “The document was then taken from the container, and found to be in apparently the same condition as when packed, with no signs of mold, or obvious evidence of further cracking,” a relieved Clapp wrote.

Stout took a series of photo graphs of the entire document, and focused on those areas that were cracked and deteriorated. At about 5:30 p.m., the document was placed in the bronze container and returned to the vault for the night. Stout and Ehrlich would begin work in earnest the next day.

The following morning, a Thursday, Stout and Ehrlich entered the workroom by 9:00 a.m. to begin their delicate task— repairing and restoring the Declaration that Timothy Matlack had so carefully engrossed 166 years earlier.

The first and most critical step was removing the Declaration of Independence from its mount, a heavy pulp board covered with paper, with a frame of green velvet glued to it. Atop the mount, a rectangular strip of tissue paper, about three- quarters of an inch wide, had been pasted— with an adhesive that consisted of part glue and part paste— the outer dimensions of which conformed to the dimensions of the Declaration. At one point, the Declaration of Independence had been pasted down at the margins on this strip, but, in 1940, it had been detached from the mount. Still, Clapp noted in his report, Stout and Ehrlich made it clear that the tissue had “re-adhered on the upper, side, and especially the lower margins, while in other places on these margins the tissue was left adherent to the document instead of the mount.”

Worse, along the upper margin, the document had in several places “been fixed firmly into place with copious glue in an effort to stop the extending cracks,” meaning that it would be more difficult to detach the Declaration of Independence from its mount. The restorers noted that “practically the whole of the detached upper right- hand corner had been glued down in this manner,” as had the portion of the document “surrounding the crack above the capital letter ‘S’ in ‘States’ in the heading.” Perhaps most disruptive of all, at one point— perhaps also in 1940— someone had made an attempt to “re unite” the detached upper right- hand corner of the document to the main mount by means of a strip of “scotch cellulose tape, which was still in place, discolored to a molasses color.”

Much to the restorers’ chagrin, “in the various mending efforts, glue had even been splattered in two places on the obverse of the document.” The risk of trying to restore the document was that it might be damaged further. Tearing could occur as restorers attempted to detach the Declaration of Independence from its mount or remove glue from the document’s face.

With the hands and eyes of a surgeon, Stout slowly freed the document from the mount when possible using a sharp, thin blade; when he could not accomplish this safely, he cut or sliced portions of the mount with the Declaration still adhering to it. “The whole upper right-hand corner, which had cracked away from the rest of the document and which itself contained multiple cracks, had to be thus sliced free,” observed Clapp, who watched Stout work.

Under the Declaration, at the lower left corner of the mount, Stout and Ehrlich uncovered two signatures and a date, written in pencil: “L. T. Anderson and Robt. L. Bier— January 22, 1924.” The two men, now deceased, had been employed by the Library of Congress respectively in the Manuscripts Division and the Prints Division repair shop; the date was mere days prior to the ceremony in which the Library of Congress enshrined the Declaration for public view. “ These names and dates appear to give a clue to the mounting of the document,” Clapp noted.

Under the Declaration, at the lower left corner of the mount, Stout and Ehrlich uncovered two signatures and a date, written in pencil: “L. T. Anderson and Robt. L. Bier— January 22, 1924.” The two men, now deceased, had been employed by the Library of Congress respectively in the Manuscripts Division and the Prints Division repair shop; the date was mere days prior to the ceremony in which the Library of Congress enshrined the Declaration for public view. “ These names and dates appear to give a clue to the mounting of the document,” Clapp noted.

The hours passed and Stout and Ehrlich continued their efforts. They freed the Declaration of adherent glue, paste, and paper along the margins of the reverse side and on the entire detached upper right- hand corner. They did this by dry slicing and scraping, with the occasional use of toluene and ethyl alcohol to remove stubborn adhesive— acceptable methods even today. Also, because the Declaration had been rolled so often as a scroll from top to bottom, the area that was exposed when rolled— approximately eight inches of the lower portion of the reverse side— was badly soiled. Stout scraped this section clean as well. As they worked inside, rain fell outside, raising the humidity in the workroom and causing the Declaration parchment to “relax appreciably.”

Into the evening, after they had removed most of the adhesives, they reassembled the document, obverse side uppermost, on white blotting paper, drawing the cracks together with Scotch tape, as their predecessor had. They then placed a large sheet of glass on the Declaration of Independence, weighted it down with bags of sand, and returned it to the vault.

It was 9:30 p.m. when they stopped. They had put in more than twelve hours of painstaking work, but they were far from finished.

For sixteen hours over the next two days— Friday and Saturday— Stout and Ehrlich labored on the Declaration of Independence at Fort Knox.

Working carefully from the back side, they applied sealing lute, made from Japanese tissue moistened with rice paste, to the document’s cracks. They patched two holes in the heading with vellum— one above the m in “America,” an original hole in the parchment; and one above the S in “States,” a hole resulting from a recent break. All the patches and repairs were tinted with watercolor to match the Declaration’s hue.

When they had finished, they dried the parchment, which had now relaxed due to humidity. The U.S. Army Signal Corps then came into the workroom to photo graph the Declaration of Independence. During this short period of illumination, Clapp noted in his report, it was clear that the document had shrunk “perhaps as much as an eighth of an inch laterally” thanks to the drying. He pointed out that the changes he noticed in the physical state of the Declaration during “relaxing” and “shrinking”— based on humidity— were worthwhile to observe, since they were “an indication of the conditions expected in storing and exhibiting the document.”

Finally, Stout and Ehrlich mounted the Declaration of Independence to a rag board that had been warmed overnight and secured the document with small expanding or pleated hinges at several places along the upper margin and at the two lower corners.

Before returning the Declaration of Independence to the vault, the two restorers examined the Constitution and found the document to be in good condition; the 1787 parchment had not suffered the same degradation as the Declaration since it was never displayed in direct sunlight or in rooms smoky from open fi replaces. Indeed, its size— five leaves, four for the document itself, plus the transmittal letter from George Washington— made it difficult to display and therefore had served to preserve the document for all these years. Stout and Ehrlich did remove the pulp board that had been used as filler in the case and replaced it with handmade Japanese blotting paper dabbed with a small amount of thymol dissolved in alcohol to aid preservation. The surfaces of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were protected with a layer of Japanese tissue.

At 2:30 p.m. on Saturday, May 16, the bronze case containing the two documents was returned to the vault, together with a hygrothermograph to record temperature and humidity. The compartment door was then securely closed “with the seal of the Chief Clerk in Charge, and of myself,” Clapp reported.

On May 20, 1942, Stout and Ehrlich submitted to the Library of Congress their “notes on examination and treatment” of the Declaration. Despite their work, they reported that the Declaration’s condition was “not much affected by treatment.” They believed that “near the mends” they had made to the document, the Declaration “ will buckle in time from changes in humidity.” But the Library of Congress was more optimistic in its annual report seven years later: “Frequent examinations have proved that the remedial measures were generally satisfactory.”

President Roosevelt was anxious for an update.

On October 6, he wrote a short note to MacLeish on White House stationery entitled “Memorandum for the Librarian of Congress.” Using his familiar salutation “Dear Archie,” the president’s memo was polite but pointed. “I have not talked to you for a long time in regard to the removal of valuable and irreplaceable books, manuscripts, etc. from the Library to places of safety in other parts of the country,” Roosevelt wrote. “Are you satisfied that we have taken all reasonable precautions in regard to this?”

For MacLeish, the key word in FDR’s memo was “reasonable.” Certainly, he believed that Library of Congress staffers had done everything they could to properly package and catalog the records, select the repositories, develop security protocols, and, throughout the summer of 1942, visit the university locations to ensure that the documents were being guarded and cared for— and that mold, mildew, and vermin had not compromised the condition of the records.

But the situation was far from ideal. “Your question,” MacLeish responded to Roosevelt in a secret memo on October 19, “goes to the heart of the matter which has concerned me, as I think you know, for about two years.” MacLeish summarized the library’s work to this point, including the transfer of the “principal treasures” to Fort Knox and Stout’s restorative work on the Declaration of Independence. He said he was satisfied that his team had done “everything it could do with the means at [their] disposal, and that [the library’s] most valuable materials are as safe as they can be without the construction of a properly located bombproof shelter.”

MacLeish stressed to Roosevelt that the Committee on the Conservation of Cultural Resources had expressed a desire for the construction of one or more bombproof structures, “ under adequate guard,” to protect the nation’s records. The relocation of records to inland repositories that were “fi reproof but non- bombproof” was adequate as a temporary measure but did not “provide the best protection which could be given.” Bombproof projects had reached the planning and discussion stage, but bureaucratic delays and other priorities had stalled construction. Prior to writing his response to Roosevelt, MacLeish had checked on the status of such projects with the Public Buildings Administration.

“I was informed . . . that the effort to construct bombproof shelters had been discontinued because of the situation as regards building materials and manpower,” MacLeish informed the president. Simply put, the nation’s efforts were focused on war priorities that were considered more pressing. “Whether or not this discontinuation will be made final, I am unable to say,” MacLeish added.

For now, MacLeish took some consolation that the library’s most valuable documents— “the priceless heart of the country’s greatest collection”— were safely ensconced at Fort Knox. He would continue to suffer anxiety about the security of the remaining 5,000 boxes now stored at universities in Virginia and Ohio.

Discussion Questions

- Did American Treasures teach you new details of American history? For example, did you know that July 2 — not July 4 — was the actual date the delegates voted on the question of independence?

- What incident or fact surprised you most in American Treasures?

- Who is your favorite character in the book, and why?

- Which historical figures introduced in American Treasures were new or unfamiliar to you?

- What are your thoughts about the delegates’ work in Pennsylvania? Was the creation of the Declaration — process, writing, debating, and duration — easier or more complex than you envisioned?

- American Treasures is written in a “braided narrative” format, a creative approach that switches between different time periods to tie together a theme, in this case, the founding and safeguarding of the nation’s founding documents. What do you think of this format? Does it add to the “color” of the narrative and the information presented?

- Imagine an event from the book in the context of present day. How would it differ? How would people across the colonies — and around the world — respond to “signing day,” Friday, August 2, 1776, when delegates gathered in Pennsylvania to sign the Declaration of Independence. How do you imagine the coverage — by the standards of today’s press and social media? How quickly would the news spread? What challenges exist today that the delegates did not face in 1776?

- As the book illustrates, signing the Declaration was an act of enormous courage and astounding risk. Had you considered this prior to reading the details in American Treasures? Again, imagining this action in the present day, might the delegates’ lives be more endangered?

- The book describes the amazing efforts to protect and preserve America’s founding documents. However, what if these priceless documents had been destroyed? What might have been done to preserve — or bring back — national morale?

- In describing the potential for an unsuccessful outcome of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Puleo wonders “if mere pettiness, stubbornness, hubris, regionalism, or factionalism led to the end of the brief American experiment?” How would you compare these emotions and headwinds to today’s political climate?

- Despite the enormity of the task, the process of creating a new constitution was accomplished in just 13 months. What, in your view, contributed to this amazing feat?

- How much did you know about the War of 1812 prior to reading American Treasures? The book offers a vivid description of the devastating attack on Washington, in which British troops set fire to much of the city. Were you familiar with this attack? Were you surprised to learn of Dolley Madison’s heroic efforts to save her husband’s priceless documents? How might you have reacted in her situation?

- Which actors would you choose play Dolley and James Madison in the feature film version of American Treasures?

- A significant segment of the book details the dramatic efforts to secure priceless documents in a secret location in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor. What are the notable differences — and similarities — between the efforts of Archibald MacLeish in 1941, those of Dolley Madison and Stephen Pleasonton during the War of 1812, and the 21st-century renovation of the National Archives?

- Have you been to the National Archives Building to see the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution? If not, does American Treasures inspire you to pay a visit?

- Were you surprised that Lincoln’s delivery of the Gettysburg Address lasted less than three minutes? Have you visited the Lincoln Memorial, where the address is inscribed?

- If you hadn’t been involved with this book discussion, would you have chosen to read American Treasures on your own? Do you typically read non-fiction or history?

- After reading American Treasures, do you want to read other books about related topics (American history, World War II, War of 1812) or anything else written by Steve Puleo?

Buy American Treasures

To buy American Treasures, click on a link below.

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Bookshop.org

Books-a-Million

Apple iBooks

More

An Interview with the National Archives Publication, Prologue Magazine, on my book, American Treasures

An Interview with the National Archives Publication, Prologue Magazine, on my book, American Treasures

By Stephen Puleo

I was honored that my book, American Treasures: The Secret Efforts to Save the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Gettysburg Address, was featured in the National Archives’ publication, Prologue Magazine (Fall 2016, Volume 8, No. 3)

Writer Keith Donohue interviewed me for the “Author on the Record” column.

The content of the interview follows:

American Treasures

Secret Efforts to Safeguard Founding Documents

By Keith Donohue

In the year leading up to the United States’ involvement in World War II, secret conversations began to take place over what to do about America’s most precious documentary resources. How could we ensure that these American treasures would not be destroyed in case of enemy attack?

In his new book, American Treasures: The Secret Efforts to Save the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Gettysburg Address, author and historian Stephen Puleo tells the intertwined story behind how these documents came to be written and later preserved at the Library of Congress and the National Archives.

The author of five other books, including The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War (2012) and Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 (2003), Puleo is the past recipient of the prestigious i migliori award, presented by the Pirandello Lyceum to Italian-Americans who have excelled in their fields of endeavor and made important contributions to society. Steve and his wife, Kate, live in Massachusetts.

What did you uncover in your research about the wartime travels of the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Gettysburg Address?

I was surprised and impressed with the planning and scope of this monumental effort by the Library of Congress to relocate the nation’s most important documents. In addition to the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Gettysburg Address, the Library transferred more than 5,000 boxes of important documents to secret locations during World War II – including George Washington’s diaries, James Madison’s notes on the Constitutional Convention, Lincoln’s papers, and thousands of other historically significant documents. In late 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish devised plans to move the documents if the U.S. went to war, due to fears of attack or sabotage by Germany or Japan. MacLeish directed his staff to prepare “at the earliest possible moment” detailed lists of documents and materials “which would be utterly irreplaceable,” along with an estimate of how many cubic feet would be required to house them if the U.S. entered the war.

Was this a highly publicized or controversial event?

Once the decision was made, the entire move was done in complete secrecy. After the war, MacLeish wrote of the patriotism of the repositories and the townspeople, librarians, Secret Service agents, custodians, shippers, domestic help, truck drivers, railroad personnel, and curious onlookers who maintained the secret about the largest single relocation of priceless documents, books, and artifacts in American history.

What about other times that those documents were in danger – particularly during the sacking of Washington in 1814?

The destruction of Washington in 1814–including the burning of the White House–left physical, emotional, and symbolic scars on a very young America. The British sacking of Washington had humbled us. At the same time, there was heroism. Stephen Pleasonton, a government clerk, defied a powerful Secretary of War and rescued the original, engrossed Declaration and Constitution, the Articles of Confederation, and papers of the Continental Congress. He stuffed the documents into linen sacks, loaded them onto carts, and hid them in a Virginia grist mill about two miles north of Georgetown. Believing that location was still too close to danger, he drove a wagon thirty-five miles to Leesburg, Virginia, where he hid them in an abandoned farmhouse.

Dolley Madison, the President’s wife, remained at the White House until the last possible moment, filling trunks with cabinet papers and government documents, including her husband’s voluminous notes from the Constitutional Convention of 1787, which virtually no American even knew existed. Just as British troops were bearing down on the President’s house, which they would burn, she rescued a full-length portrait of George Washington. With her final task completed, Madison and a small group left the White House with all the critical documents in a single wagon.

What is the story behind the transfer of the Charters from the Library of Congress to the National Archives in 1952?

National Archivist Wayne Grover and Librarian of Congress Luther Evans were most responsible for the transfer, after years of turf-fighting and legal wrangling. They navigated Congressional committees, logistical frustrations, and resistance from staff members. Evans came across as the altruistic visionary–he agreed with Grover that the Declaration and the Constitution should be viewed by the public, not stored away; but in so doing surrendered custody of his institution’s most precious and priceless documents. Some members of the Library of Congress staff were not happy–there was a natural rivalry between the Library and the National Archives. Just before the documents were transferred in 1952, Grover wrote to Evans and said, “History is going to say good things about you. It startled my colleagues here that a man heading a great and powerful institution should be so reasonable and generous.” Both men felt strongly that the founding documents belonged in the people’s archives, that the more Americans who could view them–under secure and protective conditions–the more deeply the citizenry would appreciate the country’s founding and its democracy. Grover went so far as to say, half in jest, “Jefferson wanted on his tombstone that he wrote the Declaration. I want on mine that I saw it safely enshrined in the Archives of the United States.”

What surprises did you find in the National Archives and in the projects supported by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission?

I was excited the first time I came across NARA’s documents on the relocation of the Charters of Freedom from the Library of Congress and the protection of documents during World War II, since this forms a main narrative theme of the book. They’re contained in Record Group (RG) 64 (Records of the National Archives and Records Administration); RG 87 (The Records of the Secret Service and Records of the Adjutant General’s Office); RG 187 (Records of the National Resources Planning Board); and RG 319 (Records of the Army Staff). What’s so interesting–and appropriate–is that the Library of Congress also contains numerous records on the documents that were moved. These two great institutions were both rivals and inextricably linked when the Declaration and the Constitution were finally moved to the Archives in 1952–appropriate that they each contain a rich collection of records on the World War II relocation.

I also found immensely helpful NARA’s Founders Online, an extensive and valuable collection of papers from, to, and about John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, George Washington, and Alexander Hamilton –good company when you’re writing about the making of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.