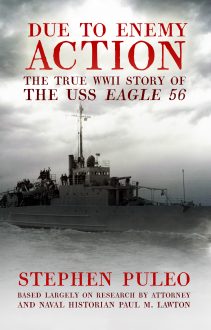

Due to Enemy Action

The True World War II Story of the USS Eagle 56

Due to Enemy Action tells for the first time a World War II story that spans generations and straddles two centuries, a story that begins with the dramatic Battle of the Atlantic in the 1940s and doesn’t conclude until an emotional Purple Heart ceremony in 2002.

Based on previously classified government documents, military records, personal interviews, and letters between crew members and their families, this is the saga of the courageous survival of ordinary sailors when their ship was torpedoed and their shipmates were killed on April 23, 1945 – the last American warship sunk by a German U-boat – and the memories that haunted them after the U.S. Navy buried the truth at war’s end. It is the story of a small subchaser, the Eagle 56, caught in the crosshairs of a German U-boat, the U-853, whose brazen commander made a desperate, last-ditch attempt to record final kills before his country’s imminent defeat.

And it is the account of how one man, Paul M. Lawton, embarked on an unrelenting quest for the truth and changed naval history.

Due to Enemy Action also describes the final chapter in the Battle of the Atlantic, tracing the epic struggle that began with shocking U-boat attacks against hundreds of defenseless merchant ships off American shores in 1942 and ended with the sinking of the Eagle 56, the last American warship sunk by a German U-boat.

Reviews

- “The character-driven narrative leaves readers with searing images of a routine day that changed lives forever.” From The Boston Globe

- “Covers the saga’s human interest aspects as well as the historical dates, facts and figures.” From The Associated Press

- “A saga of courageous survival” From Amazon.com

- “Puleo does a remarkable job chronicling … exactly what happened before, during and after the fatal day.” From the Portland Press Herald

- “Stephen Puleo’s account is a stunning tribute to men who had to be remembered in a story that had to be told.”

– Lamar Underwood, Editor, The Greatest Submarine Stories Ever Told, introducing an excerpt from Due to Enemy Action.

The truth about the USS Eagle 56

Author sets WWII record straight on East Coast sinking of Naval ship

From The Boston Globe

By Robert Knox, Globe Correspondent

April 6, 2006

Weymouth author Stephen Puleo discovered the story that became his second book at a ceremony four years ago on theUSS Salem, in Quincy. Purple Hearts were being awarded to sailors who had gone down with their ship over half a century before. At that ceremony, he met military historian Paul Lawton of Brockton, who had researched the loss of a US Navy patrol escort (a 200-foot long sub chaser) off the coast of Portland, Maine, in the last days of World War II.

The sinking of the ship and the loss of 49 crew members — the largest loss of life suffered by the Navy off the East Coast during the war — had been blamed by the Navy on a boiler explosion, but the ship’s 13 survivors believed their ship, a few miles off shore on a routine training drill, had been sunk by a German U-boat. A few of them said they had even seen the enemy submarine.

The Purple Heart ceremony was the result of Lawton’s success in persuading the Navy to overrule its own Court of Inquiry, the only such action in Naval history, and officially conclude the ship was lost “due to enemy action.”

Puleo’s book, “Due to Enemy Action: The True World War II Story of the USS Eagle 56,” takes its title from righting the record. He will speak on his book Monday at the Brockton Public Library.

“It was an intriguing story,” Puleo said. “An incredibly moving story.”

Puleo — a journalist, public relations consultant, and the author of ‘”Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919,” a Boston-area bestseller — took off from Lawton’s hundreds of pages of research. Puleo interviewed three Eagle 56 survivors, plus family members of some of those lost, and wove their stories into his narrative of the ship’s sinking.

His sources include Phyllis Westerlund Kendrick, the widow of Ivar Westerlund of Brockton, who went down with the ship. A casual comment by one of the Westerlunds’ three sons over drinks in a Brockton pub first alerted Lawton to the survivors’ belief that a German sub — and not a boiler malfunction — sank the Eagle 56.

The tale’s bite comes not only from the Navy’s initial blindness to the cause of the ship’s loss, but from the shock of losing a ship to enemy fire off the Atlantic in April of 1945, so near the end of the European war. By then, US counter-submarine forces were so effective that the German command considered it almost suicidal to send U-boats into the Atlantic.

Because they had broken the German code, the Allies were able to anticipate U-boat movements, and US intelligence knew that a few German subs had been sent across the ocean in 1945 in the desperate hope that renewed attacks on American ships could lead to better surrender terms for Germany. But this information was so closely guarded that only generalized warnings were passed to commanders.

Official secrecy was part of the legacy of the disastrous first year of the Battle of the Atlantic when German U-boats sent 600 American merchant vessels — tankers, freighters, barges — to the bottom of the ocean in eight months, and civilians on the coast of Massachusetts watched ships burn in the night. Ignorance of these disasters, abetted by wartime censorship, is so widespread that readers have told Puleo they were shocked to learn about them from his book.

One reader told him that as a child living in Scituate during that year he listened to the thud of explosions at night that shook the house. His mother said naval gunners were practicing. In fact, U-boat commanders were feasting on merchant ships in what they called “the great American turkey shoot.”

American productive capacity and a committed labor force had long turned the tide in the Atlantic by the time the Eagle 56 — a World War I-era ship assigned to lesser tasks — was given the job of towing targets to sea for practice bombing runs.

Puleo’s character-driven narrative leaves readers with searing images of a routine day that changed lives forever. Ivar Westerlund, home on leave, barely caught an early morning bus in Brockton in time to make it back to Portland for the ship’s departure; his biggest worry was being marked AWOL. Harold Glenn jumped off a Portland bus to kiss his wife goodbye before going to the ship; she never saw him again. John Scagnelli, the ship’s engineering officer, Johnny Breeze, and Harold Peterson — major sources for “Due to Enemy Action” — barely survived a half-hour in the frigid Atlantic water before rescue.

Puleo says he feels “a certain admiration” for the people in his story, many of whom attended a 60th anniversary memorial for the Eagle last year. “They don’t get thrown by much,” he said. Breeze and Peterson, in their 80s, drove the seven-hour trip together from upstate New York to Portland.

World War II still casts a long shadow, Puleo said.

“This story starts in the ‘40s,” Puleo said of the fate of the Eagle 56, ‘”and doesn’t end until last year.”

Copyright 2006 Globe Newspaper Company.

Book describes 57-year aftermath of sunken U.S. warship

From The Associated Press

By Norman N. Brown

“Due to Enemy Action” chronicles an episode of U.S. naval warfare that occurred near the end of World War II and which could have been lost to history were it not for a barroom conversation 50 years later.

Author Stephen Puleo uses a low-key approach as he covers the saga’s human interest aspects as well as the historical dates, facts and figures.

On April 23, 1945, with Germany’s defeat certain and the end of the war in Europe only weeks away, the German submarineU-853 torpedoed a U.S. Navy sub chaser, the USS Eagle 56.

The Eagle was attacked near its home base of Portland, Maine. Its hull was split in two and the ship sank quickly following an explosion. Only 13 of its crew survived; 49 were lost.

For reasons still unclear, the naval court of inquiry concluded that the sinking was caused by the explosion of a ship’s boiler.

It has been speculated that naval authorities at Portland might have wanted to avoid criticism and embarrassment for having allowed an enemy submarine to operate so close to the mainland at a time when the war was ending and the threat of U-boats had been almost totally dismissed.

Some naval authorities disagreed with the court’s findings, but this dissent was lost in the turmoil of the European war’s last days and in the climate of secrecy surrounding the Allies’ anti-submarine warfare intelligence operations.

A few weeks after the Eagle was sunk, the U-853 torpedoed and sank the SS Black Point, an American collier, off Rhode Island. This was after German Adm. Karl Doentiz had ordered all U-boats to cease hostilities and surrender to the Allies. The German sub, which was promptly found and destroyed by an American hunter-killer task force, was the last U-boat to sink both a U.S. naval ship and merchant ship in World War II.

Because the sinking of the Eagle was not attributed to enemy action, the surviving crew members were declared ineligible to receive Purple Hearts. The story of the Eagle was crowded out of the news by victory in Europe and soon after by victory over Japan.

It was not until March 1998 that the episode was revived, sparked by a casual conversation in a bar among two sons of one of the Eagle‘s crew members and a lawyer, Paul Lawton.

Lawton, also a naval historian, knew about the U-853 and theBlack Point, but had never linked the submarine to the sinking of the Eagle.

Lawton searched for survivors of the Eagle and heard their views on the episode. They agreed that there had been no boiler explosion; some had even briefly seen the attacking U-boat on the surface. None had thought to challenge the findings of the court, and some hadn’t even known about the inquiry and its verdict.

Lawton approached the U.S. Navy and requested access to all documents relating to the loss of the Eagle. He got the runaround at first, but pressure from various sources eventually persuaded the Navy to recant its findings about an internal explosion.

The Navy awarded Purple Hearts to the crew of the Eagle or their survivors during a ceremony in 2002 aboard the USS Salem in Quincy, Mass.

The remains of U-853 are known and have been dived on frequently, but the wreck of the Eagle has not yet been found.

“A saga of courageous survival”

From Amazon.com

Due to Enemy Action tells for the first time a World War II story that spans generations and two centuries, one that begins with the dramatic Battle of the Atlantic in the 1940s and doesn’t conclude until the Purple Heart ceremony aboard the USSSalem in 2002. Based on previously classified government documents, military records, and letters between crew members and their families, Due to Enemy Action is a saga of the courageous survival of ordinary sailors after their ship was torpedoed, and the memories that haunted them after the U.S. Navy buried the truth at war’s end. It’s the story of a small subchaser, the Eagle 56, caught in the crosshairs of a German U-boat, the U-853, whose brazen commander doomed his own fifty-five-man crew in a desperate, last-ditch attempt to record final kills before his country’s imminent defeat.

This story is drawn from extensive personal interviews with major players: the three living survivors; a senior naval archivist who worked with German naval historians after the war to catalog U-boat movements; the son of the man who commanded America’s sub-tracking “Secret Room” during the war; and Paul Lawton, whose dogged efforts changed history.Due to Enemy Action also describes the final chapter in the Battle of the Atlantic, tracing the epic struggle that began with shocking U-boat attacks against hundreds of defenseless merchant ships off American shores in 1942, a bold offensive masterminded by German Admiral Karl Doenitz, father of the U-boat service, and ends with the last sinking of an American warship by a German submarine — the sinking of the Eagle 56.

‘Enemy Action’ revisits WWII attack in Maine waters

Portland Press Herald

William David Barry

Three decades ago my friend, the late Horace G. Morse, a well-informed maritime enthusiast, told me in no uncertain terms that a Navy vessel he called “an Eagle boat” had been torpedoed off Cape Elizabeth toward the end of World War II.

According to him, the official inquiry had been a “cover-up,” with blame being put on a boiler explosion. Though I’ve never been big on conspiracy theories, I knew Horace was honest and had a solid grasp of history. So I believed there was at least a core of truth to the statement.

“Due To Enemy Action,” a new book by Boston writer Stephen Puleo, proves Horace’s account to be quite accurate, though the “cover-up” part remains under-examined.

On April 23, 1945, the subchaser USS Eagle 56 was sunk in these waters by a German submarine, almost certainly U-853. Forty-nine Eagle crewmen were killed and 13 rescued from the icy waters. A court of inquiry was hastily convened and, in spite of the crew members having spotted the U-boat, the loss of the vessel was officially given as “due to the explosion of its boilers.” The survivors were quickly reassigned, and as far as the authorities were concerned, the incident forgotten.

However, in the minds of the crew and in local folklore, a U-boat had sunk Eagle 56. It took Paul M. Lawton, an attorney whose father served as a World War II infantryman, to unravel what happened.

With the help of survivors, historians and politicians, Lawton produced enough evidence to have the findings of the original board of inquiry corrected. It proved a newsworthy event when, on May 1, 2001, the director of Navy history informed the secretary of the Navy that Eagle 56 was sunk “due to enemy action” and that the crew should be awarded Purple Hearts.

Puleo does a remarkable job chronicling Lawton’s research and exactly what happened before, during and after the fatal day. Using the recollections of participants and official records, both American and German, he identifies the U-boat, its commander and the Nazis’ last-ditch efforts.

He also notes that the U.S. Navy’s “secret room” (which cracked the German code) was well aware of the arrival of U-853 in the Gulf of Maine. Indeed, general warnings had been sent to the base commander at Portland. However, because the alert was not specific (intelligence did not want to tip its hand concerning the breaking of the code), no special precautions were taken.

Built in 1919 as one of 60 subchasers, Eagle 56 already had an active World War II record, having rescued survivors of the destroyer Jacob Jones II off Delaware in February 1942 and having been engaged in various projects off Florida. Assigned to the U.S. Naval Frontier Base Portland, she had just been refitted and was working as a towing vessel for targets. By weaving the lives of sailors and families, German submariners and U.S. intelligence operatives together, Puleo gives the reader an intimate understanding of the event.

What is missing is why the Eagle was at a dead stop in the water when sunk and why the board of inquiry chose to ignore evidence. Indeed the reader is made privy to precious little about the vessel’s skipper, Lt. James Early (who was killed with all but one of the vessel’s officers), Portland base commander Earnest Freeman or commander of the First Naval District Adm. Felix Gygax. Indeed, the latter appointed the court of inquiry (and was apparently skeptical of the findings). We are also missing the context of Portland in its years as a major Navy base.

As good as the book is in answering what happened, the whys remain elusive. If we accept that this is beyond the scope of this volume, then perhaps what we really need is a comprehensive overview of World War II in the Gulf of Maine.

Portland played major roles in the battle of the Atlantic. Included would be the Todd-Bath shipyards, the Montreal Pipe Line and the actions of the destroyer arms and convoys.

One could also look into such incidents as the destruction of U.S. Navy Blimp K-14 off Mount Desert in 1944. In Capt. Alexander W. Moffat’s “A Navy Maverick Comes of Age” (Wesleyan University Press, 1977), it is claimed, persuasively, that a U-boat shot down the blimp. It is time that the fog of the second world war was lifted from our waters.

William David Barry of Portland is a writer and historian.

Copyright © 2005 Blethen Maine Newspapers Inc.

Excerpts

April 23, 1945, 12:14 P.M

Helmut Froemsdorf

aboard the U-853

Gulf of Maine

For two difficult months at sea, it is likely that Helmut Froemsdorf had dreamed of this moment. His boat had been forced to remain submerged like a frightened rabbit for virtually the entire trip across the Atlantic, crawling beneath the surface to avoid detection and likely destruction from Allied ships and planes, which had killed more than one hundred U-boats and their crews in the first four months of 1945. The fifty-five men aboard the U-853 would be growing restless and irritable, eating bland food, breathing stale air, living and working in cramped quarters alongside shipmates who had not changed clothing or showered in weeks due to a lack of space for personal effects and restrictions on the use of freshwater.

Now, the time for cowering and restlessness was over; precision and daring were the orders of the day. Helmut Froemsdorf, who had turned twenty-four years old less than a month earlier, would truly come of age on this raw April day in the Gulf of Maine. He was operating the U-853 under power of her electric motors as she crept, submerged, toward the Eagle 56, the U-boat’s sound masked by the noisy wake of the American destroyer, Selfridge, seven miles away. Froemsdorf would have celebrated his good fortune. The American subchaser was at a dead stop and made an easy target for theU-853’s torpedoes.

As he drew a bead on the Eagle 56, Froemsdorf may have recalled the glory days of his predecessors—of Sommer’s bravery in the open Atlantic, of Hardegen’s and Mohr’s dramatic kills along the American East Coast during the Second Happy Time in 1942. He also may have thought about the last message he had received from Admiral Dönitz, on April 11, one that rose to the unwavering defense of Adolf Hitler, calling him the “single statesman of stature in Europe.”

But perhaps it was the last portion of Dönitz’s April 11 message that was uppermost in Froemsdorf’s mind as he prepared to attack the Eagle 56, words that trumpeted the glory of the Kriegsmarine and its willingness to “fight to the end,” words that heralded the bravery of its U-boat captains who would never “think of giving up [their] ship” and whose “bearing in the severest crisis of this war will be judged by posterity.”

With the U-853 less than six hundred yards from the Eagle 56, Froemsdorf ordered his torpedo crew to fire.

Discussion Questions

- Parts of Due To Enemy Action are written in a narrative style, through the eyes of characters. How does this style compare with other works of history you’ve read? Does the narrative style enhance or hinder your understanding of the history and the time period?

- Before reading Due To Enemy Action, how much did you know about the Battle of the Atlantic and German U-boat attacks off American shores? Were you surprised that the torpedo attack of the Eagle took place so close to the coast in Portland, Maine?

- In telling the Eagle story, the book includes intimate personal stories of the Eagle crewmen — both survivors and those who were killed. Whose story did you find most poignant, and why?

- The Naval Court of Inquiry originally concluded that the sinking of the Eagle was caused by the explosion of a ship’s boiler. Why do think the court reached this conclusion, despite compelling eyewitness accounts that suggested otherwise?

- In your opinion, whose testimony best refuted the boiler explosion theory?

- What did you think of Helmut Froemsdorf, commander of the U-853, and his determination to record “final kills,” despite the fact that it led to the deaths of his 55-man crew?

- In addition to telling the Eagle story, Due To Enemy Action provides information about other World War II events and circumstances, such as a comprehensive “behind-the-scenes” depiction of the subtracking “Secret Room.” Did the book help you learn — or learn more — about World War II? What new information did you learn about the war?

- In 2002, the Navy awarded Purple Heart medals posthumously to the 49 sailors who were killed, and to survivors Scagnelli and Peterson. However, the Navy did not award Purple Hearts to Johnny Breeze and 10 other Eagle survivors. Do you agree with this decision?

- At a ceremony on April 23, 2005, all four living survivors of the USS Eagle 56 were in attendance to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Eagle’s sinking. If you had the opportunity to meet one of the survivors, what would you say, or what questions would you ask?

- If you hadn’t been involved with this book club, would you have chosen to read Due To Enemy Action on your own? Do you typically read non-fiction or history?

- After reading Due To Enemy Action, do you want to read other books about related topics (World War II, the Battle of the Atlantic, submarine stories and history, anything written by Steve Puleo?)

Buy Due to Enemy Action

I’m thrilled to announce that my book, Due to Enemy Action: The True World War II Story of the USS Eagle 56, first published in 2005 and converted in 2012 to “e-book only” status, is back in book form! Readers can now order DTEA in hardcover ($27) or paperback ($17) form from Untreed Reads, the ebook publisher who will also continue to make it available in electronic form. You can order your copy in any format here.

More

“An eagle to scour the seas”

A noble World War II record

Bombing practice in Portland, Maine

The sinking of the Eagle 56

“An eagle to scour the seas”

Approximately 200 feet long, with a 33-foot beam, the Eagle PE-56 was hardly a state-of-the-art ship during the Second World War. In fact, she was a vestige of World War I, when, in June of 1917, President Woodrow Wilson summoned Henry Ford to Washington and asked the mass production expert whether he could convert his auto production lines to shipbuilding. Wilson urged Ford to build antisubmarine vessels to combat the German U-boat menace in World War I. “What we want is one type of ship in large numbers,” Wilson had said. No facilities were available at the Navy yard to build the new craft; thus, Wilson and then Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels asked Ford if he would undertake the task in his Detroit factories.

Ford agreed, and in January of 1918, the United States government issued a contract for Ford Motor Company to build 100 PE (Patrol Escort) class boats by December 1 of the same year. It was actually a misnomer to call the

USS PE 56 the USS Eagle 56, though it was done often; the “Eagle” moniker for this entire PE class of vessel came from a December, 1917, Washington Post editorial calling for “an eagle to scour the seas and pounce upon every submarine that dares to leave German or Belgian shores.” Ford set up production at his 1,700-foot-long enclosed assembly line on the Rouge River in Dearborn on the outskirts of Detroit.

The first of the cookie-cutter Eagle boats was launched on July 11, 1918, and six more boats were completed on schedule. But succeeding ships did not follow as rapidly. Ford’s initial estimates that he could fulfill the Navy’s expectations proved overly optimistic, due mainly to the inexperience of his labor force and supervisory personnel in shipbuilding. When World War I ended and the armistice was signed in November of 1918, only 60 Eagle boats were completed and the contract was suspended. Of these, seven were commissioned in 1918, and the remaining 53 were commissioned in 1919.

A noble World War II record

The Eagle 56 (the Eagle class boats were numbered 1-60) was commissioned on October 22, 1919, and launched on the Detroit River on November 13. Like many of the Eagle boats, she reached the North Atlantic by way of the Great Lakes’ canals and the St. Lawrence River. On the way, according to Seaweed’s Ship Histories, she was held up by ice in Quebec until May 8, 1920, and finally reached the Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Navy Yard one week later. She was assigned to the District of Columbia Naval Reserve Force in November of 1921, and in 1926, was transferred to Baltimore, Maryland, where she continued duty as a Naval Reserve training ship. The PE-56 was one of only eight of the original 60 Eagle Boats to see service with the U.S. Navy during World War II.

The Eagle 56 had a noble World War II record. Early in the war, her crew had rescued survivors from the USS Jacob Jones II after the destroyer had been sunk by torpedoes from a German U-boat, the U-578, off the Delaware coast. The date was February 28, 1942, less than three months after Pearl Harbor; the Jacob Jones was the first U.S. warship sunk by a German U-boat within American coastal waters in World War II. Of the nearly 200 crew members aboard the Jacob Jones, only about two dozen escaped the doomed ship in life rafts, and several of those men were killed when their ship’s depth charges exploded as she sank.

The other surviving crew members were spotted by an Army observation plane in the early morning hours of February 28, 1942. The pilot reported their position to the Eagle 56, which was then stationed at Cape May, New Jersey, as part of Inshore Patrol. Her crew fought rising seas — and the knowledge that a U-boat was in the area — to reach the stranded Jones crewmen, and two hours after the plane had spotted the life rafts, the Eagle 56 radioed back to Cape May: “Am picking up survivors from the USS Jacob Jones – details later.” The details were few; the Eagle 56 had rescued 12 survivors and one of them died on the way back to shore. For the next two days, planes and ships searched without success for other Jacob Jones survivors.

Bombing practice in Portland, Maine

The PE-56 did other important work. In May of 1942, she reported to Key West, Florida as a sound training school-ship conducting exercises in anti-submarine warfare tactics. In 1943, she had participated in the development of the Navy’s top-secret “homing mine,” or anti-submarine torpedo by acting as an acoustic target during testing trials.

Portland, Maine became the Eagle’s home base in late June of 1944, and the “old girl” or the “tub” (as the crew affectionately referred to the 25-year-old vessel), was relegated to towing a green cylindrical target float, which was mounted on a sled at the end of a 500-yard cable, off the coast of Cape Elizabeth. The green float, nicknamed “the pickle” by the crew, was used for bombing practice by Navy “Avenger” torpedo bomber aircraft from the Navy Air Station in Brunswick, Maine. The Navy and Marine flyboys needed the practice before they shipped out to battle the Japanese in the Pacific.

This was important work, but it was not considered tough or hazardous duty. In fact, many of the Eagle’s crew members had seen action in the Pacific and off the coast of North Africa, and had been transferred to the Eagle 56, which was considered much less dangerous, and a “plum” location to finish the war. The ship was armed with depth charges, but by 1945, the PE 56 had her Y-gun removed to accommodate target-towing gear and her aft four-inch deck-gun had been replaced by a single .50 caliber machine gun. In short, her days of taking part in any real combat were over.

The sinking of the Eagle 56

On April 23, 1945, shortly after noontime, while on a routine target-practice session, the Eagle 56 exploded just a few miles off the coast of Portland. Forty-nine of her 62 crew members perished; the survivors became known as the “Lucky Thirteen.” The official Court of Inquiry decision ruled that a boiler explosion had doomed the ship.

It wasn’t until 57 years later that the U.S. Navy reversed the decision and conceded that the U-853 had torpedoed the Eagle 56 and sent her to the bottom.