I share information in this section first with loyal readers on my mailing list. If you’d like to be added to the list – and receive 3-4 updates a year – simply email me at spuleo@aol.com. Click here for my most recent newsletter.

All the latest news about The Great Abolitionist!

History Happy Hour Episode 203: Abolitionist Charles Sumner – Hosts Chris Anderson and Rick Beyer welcomed me online to talk about The Great Abolitionist. It was fun to do and offered a chance for good two-way discussion. Catch my interview, and ongoing episodes airing on Sundays at 4:00 pm ET, at History Happy Hour, where history is always on tap.

Boston.com Book Club presents 4 takeaways from The Great Abolitionist discussion – The Boston.com Book Club selected The Great Abolitionist as its May 2024 read, a wonderful honor. This was followed by a virtual discussion with Totsie McGonagle of Buttonwood Books, which led to a story by the Globe’s Annie Jonas entitled, “4 Takeaways from book club’s The Great Abolitionist discussion.” You can read the story here.

Thanks for a Wonderful Spring 2024 Book Tour for

The Great Abolitionist!

Where to begin? It’s been a whirlwind and exhilarating Spring, and I’ve enjoyed every minute of The Great Abolitionist book tour! I hope these additional photos in this section give you a real sense of the excitement and enthusiasm of my TGA events. They are in no particular order, but serve to highlight an amazing Spring speaking season. I also wanted to offer my thanks to the following organizations which helped me launch the new book (note – a special thanks to bookstores follows below!)

My gratitude to so many organizations for making The Great Abolitionist launch so special!

I have thanked and continue to thank so many organizations, bookstore staffers, librarians, podcasters, moderators –and most of all, YOU, dear readers – for a memorable spring book tour for The Great Abolitionist: Charles Sumner and the Fight for a More Perfect Union. As an author, I could not have asked for a better launch! The photos in this introduction show just a few of the many highlights from the tour.

My 20-plus events over this period (most live, a few virtual, and a few podcasts) took place in libraries, country clubs, bookstores, senior citizen centers, TV studios, and hotel conference rooms. The overall response from hundreds of readers was truly gratifying, and the dozens upon dozens of questions I received during presentations were impressive and insightful. This tour reminded me again (not that I really need reminding) how much I enjoy meeting and interacting with readers. Special thanks to all of the organizations listed below:

*The Friends of the Hull (MA) Public Library, Buttonwood Books, and the beautiful Nantasket Beach Resort for sponsoring my launch event! *The Andover (MA) Book Store and the historic and majestic Memorial Hall Library in Andover for a memorable setting and a great audience. *The Marshfield (MA) Council on Aging for a jam-packed event! *The American Inspiration Series from American Ancestors/New England Historic and Genealogical Society who partnered with WGBH (public broadcasting) for an enjoyable virtual event! *The Tufts Memorial Library in Weymouth, MA for a spectacular “hometown event” with nearly 100 participants. *The Winchester (MA) Public Library, a beautiful place to do a presentation and amazing lovers of history attended!

*The James Library and Center for the Arts in Norwell, MA, a gem on Boston’s South Shore and a wonderfully engaged group of members! *The Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, CT, which sponsored a spirited virtual event moderated by long-time Connecticut journalist and television host, Duby McDowell. *The Reading (MA) Public Library, whose attendees made me think – and think again! – with their outstanding questions! *The Barnes & Noble store in Hingham, MA, which hosted a wonderful Saturday afternoon signing event (my 690th as an author!). It’s my “home” B&N, and I was thrilled that so many family members and friends stopped by! *The Charlotte and William Bloomberg Medford (MA) Public Library, where more than 70 people showed up to discuss The Great Abolitionist. Medford is a city with a great history, and it showed! *The Friends of the Wolfeboro (NH) Public Library Book & Author Luncheon. I was thrilled to participate in this memorable event, along with New York Times bestselling author Lisa Gardner, to kick off the Wolfeboro/Lakes Region summer season! What a fantastic event! More than 150 enthusiastic readers turned out for the library’s big summer fundraiser.

*The Forbes House Museum and the Milton (MA) Public Library, where an engaged crowd of readers and history-lovers attended for this special event. I spent some quality time at the Forbes House while researching Voyage of Mercy, and the Town of Milton made Voyage its community-wide read a few years ago. *The Robbins, Library in Arlington, MA, where a great crowd braved scorching heat to make my final in-person Spring TGA event very special!

A special salute to bookstores for their help with launch!

I can’t thank bookstores enough for their tireless efforts to support events and authors! I’m especially grateful for all the stores who helped make The Great Abolitionist a success this spring.

Photos in this section show me at a wonderful display of my books at The Country Bookseller in Wolfeboro, NH (thanks to owner Autumn Siders!); owner Kathy Detwiler and Totsie McGonagle of Buttonwood Books and Toys (Cohasset, MA) enjoying a moment at my Hull presentation behind a display of my new book (Buttonwood handled several events for me this spring!); Lauren Tiedermann (holding my book), co-owner of Book Ends in Winchester, MA, with me behind a stack of TGAs; Harriet Lyons (right) of Whitelam Books in Reading, MA shown with me and local historian librarian Jocelyn Gould of the Reading Public Library; Hingham Barnes & Noble’s Ashley O’Regan and I each holding a copy of The Great Abolitionist; and the wonderful team at the Andover Bookstore shown below with me from left: Chris Rose, Karen Harris, Caroline Buchta, and Sarah Klock. My thanks also to Storybook Cove bookstore in Hanover, MA, for managing my Weymouth event; Maxima Book Center in Lexington, MA for handling my Arlington, MA event, and in Cambridge, MA for supplying books for my American Ancestors virtual event. Finally, a personal photo from Galaxy Bookshop in Hardwick, VT, an independent bookstore that didn’t specifically manage one of my events this spring, but, I’m happy to say, is carrying The Great Abolitionist. That’s my niece, Katie Rose Logan, proudly displaying her copy! Thanks to all of these bookstores for being so good to me!

Looking Ahead to Fall Events

The Spring season has wound down, but I have several events already lined up in the Fall! These include: a visit to a bookstore in Montgomery, Alabama; the Nashua, NH Public Library; the South Kingstown, RI Public Library; and events in Scituate, Wellesley, and Winthrop, as well as the prestigious UMass-Dartmouth literary luncheon! Plus, the Bridgewater (MA) region has selected The Great Abolitionist as its nonfiction Community Read for the fall! (Sue Monk Kidd’s The Invention of Wings is the fiction choice). And more events are being scheduled. You can check regularly on my website “Events” page!

The Great Abolitionist has a great team supporting it

(and supporting me)!

I’ve said it often (as have many authors) – writing may be a solitary act, but “authoring” is not. Researching, writing, editing, and marketing a book requires that an author have a strong support structure, a team to call on to provide encouragement, expertise, and excitement. I was so fortunate to rely on so many talented people who helped bring you The Great Abolitionist (several of whom have been a critical part of assisting me with other books as well). I want to recognize them here – with all gratitude and humility – for the great work they’ve done and continue to do:

My friend Charlotte Hannan, shown with me at the Barnes & Noble event, will be entering her senior year at Harvard, and assisted me with the research of TGA. Her work was thorough, intuitive, and exemplary and always right on the money. I’ve known Charlotte for a long time and have always said, “she works so hard and cares so much.” Truer than ever with her work on TGA!

It’s appropriate that I’m holding open the TGA back cover flap while standing with my friend, Erin Leone! Erin, a talented photographer with her own business and a rising senior at George Washington University, took my new jacket photo (which I love). The photo also appears on all social media sites and TGA marketing materials (including on my website and at the top of this newsletter)! You can see more of Erin’s outstanding work at Erin Leone Photography.

My dear friends, Paula Hoyt and Ellen Keefe, have been with me on my author journey since the beginning – and have been amazing friends since long before that! How blessed I am to have their love and support in so many ways – but most specifically, as tough, talented “advance readers” of my TGA manuscript (and virtually every other manuscript too). I think I submit very clean manuscripts to my publisher, and Paula and Ellen are two big reasons why (my wife Kate is also, but more on her soon). They are smart and have become experts at spotting inconsistencies, omissions, grammar errors, typos, or saying “something just doesn’t sound right” in the manuscript. Ellen and Paula also do a great job acting as ambassadors for my books, always providing encouragement, and being there to offer suggestions and advice if I need them (and sometimes, even if I don’t – lol).

You may be noticing a trend here – It’s always a massive plus when you have great friends who are also talented! Such is also the case with Sue Hannan (shown here with me at B&N), who handles marketing and expertly manages content and navigation for my website. I’m biased, but I think it’s one of the best! Sue takes great pride in keeping content fresh and dynamic (as evidenced by her rapid implementation of the new TGA section of my website), and also helps spread the word through social media. Her ideas, creativity, and excellent marketing skills help me connect with readers in the best possible way!

When I wrote her acknowledgment in The Great Abolitionist, I referred to my friend and sister-in-law, Pat Doyle, as the unsung hero in my author life. Since the beginning, she has been there for me, offering assistance and encouraging words always. She has attended a huge number of my nearly 700 author appearances, and has contributed many wonderful photos to my website, social media pages, and these newsletters (including a large number in this issue!). She also provides a helping hand in ways too numerous to list – she is simply always ready to help. I am grateful for her friendship, love, enthusiasm, interest, talent, and bedrock support.

The love and friendship my wife Kate and I have shared for more than four decades is my greatest joy and most profound blessing. As I said in my TGA acknowledgment, she is the first to hear my ideas, the first to offer insights, the first to read my manuscripts, the first to know when things are going smoothly or if I’ve hit a rough patch. She is talented, inspirational, and helpful beyond words – I’m immensely proud of her – and during this TGA tour, she was always there — selling books, greeting readers, taking photos, and brightening every room she entered. She is, simply, “present on every page” of my writing and of my life. The Great Abolitionist is dedicated to Kate from the bottom of my most grateful heart.

What Others are Saying About The Great Abolitionist

I’ve already shared with you some wonderful blurbs (see article below) that I received from authors and historians, and a great pre-publication “starred review” from Kirkus Reviews. Among other things, Kirkus called The Great Abolitionist “a wonderfully written book about a true American freedom fighter.” The Great Abolitionist also received a terrific “starred review” from Publishers Weekly, which exclaimed: “Readers won’t be able to get enough of Puleo’s indomitable Sumner.” Enjoy the full review here. In addition, I want to thank Harvard Law School student Tom Koenig for his thoughtful and outstanding review of The Great Abolitionist in American Purpose magazine, where he is also a contributing editor. Koenig called TGA a “masterful new biography” of Sumner and really captures the essence of the book in his thorough review. Some early reviews from readers are in and I’m very pleased! Here is a collection of advance reviews from Netgalley.com that shows readers have enjoyed The Great Abolitionist!

“I’m pleased to say that we have collected these and other reviews for The Great Abolitionist all in one area of my website for your reading pleasure (just scroll down to the “Reviews” tab on the Book page.) If you’d like to see what readers are saying about my books and presentations, check out the Readers Respond page of this website.

And thanks to these authors and historians for their generous blurbs…

Also, I have received several wonderful “back cover” blurbs that you’ll see (in their entirety or in part) when the book comes out – but I thought you’d like a sneak preview now.

I am honored to have thoughtful and generous blurbs from some outstanding non-fiction authors and historians (James O’Toole, Chris Gorham, Bill Kole, Eric Jay Dolin, Gregg Olsen), as well as two New York Times bestselling fiction authors (William Martin and Dennis Lehane) who often delve into historical settings and narratives in their novels. I’m thankful to all of these authors who took the time to read the book and offer their great endorsements.

- Dennis Lehane, author of Small Mercies: “Stephen Puleo’s masterful account of Charles Sumner, a prickly, conflicted paradox of an American giant, is told with verve and gusto. It’s a vibrant, important story whose echoes still reverberate in our current day. A wonderful read.”

- James M. O’Toole, University Historian and Clough Professor of History Emeritus at Boston College: “Charles Sumner, a lifelong crusader for human rights, has not been the subject of a comprehensive biography for more than fifty years. Stephen Puleo fills that gap with this deeply researched and dramatic retelling of Sumner’s courageous life and work.”

- William Martin, New York Times bestselling author of The Lincoln Letter and December ’41: “Sometimes, a giant needs a little help. He passes through history, leaving huge footprints that are filled by time and covered over by events. Well, in Stephen Puleo’s superb new biography, Massachusetts Abolitionist Charles Sumner gets all the help he needs. In prose that is perceptive and propulsive, in scenes that are powerful and dramatic, Puleo brings Sumner vividly to life. Once more, the Great Abolitionist drives the momentous events of the mid-Nineteenth Century. Once more, the strength of his character, the intensity of his personality, and the honor of his crusade shine before us. And once more, Stephen Puleo delivers a book that will captivate the general reader and reward the serious historian, too.”

- Gregg Olsen, New York Times and Amazon Charts bestselling author of The Amish Wife and If You Tell: “When it comes to impeccable research – the kind that surprises and never rehashes – no one does it better than Stephen Puleo. The Great Abolitionist is a literary and historical triumph and is sure to be on many year-end “best” lists in 2024.”

- William J. Kole, veteran journalist, author of THE BIG 100: The New World of Super-Aging : “Nearly two centuries on, Charles Sumner’s name still drops loudly in Boston, yet few appreciate the enormity of his impact. Stephen Puleo’s The Great Abolitionist is at once a revelation and an appeal to our better angels to heed the lessons Sumner’s example can teach us.”

- Eric Jay Dolin, author of Left for Dead and Black Flags, Blue Waters: “Charles Sumner was a principled man of unshakable conviction, who fought the good, noble, and heroic fight against slavery, and he deserves to be remembered as a great statesman and one of the foremost champions of civil rights. He also deserves a compelling and wonderfully-written biography, which is what Stephen Puleo has provided.”

- Christopher C. Gorham, author THE CONFIDANTE: The Untold Story of the Woman Who Helped Win WWII and Shape Modern America: “In THE GREAT ABOLITIONIST we feel the cold wind in the cobbled streets of mid -19th century Boston and hear the stifled sobs at Abraham Lincoln’s deathbed in April 1865. The subject of Stephen Puleo’s eighth book is Charles Sumner, a lawyer and U.S. Senator who was a leading voice of antislavery during the tumultuous two decades before the Civil War. As the nation was adding Texas, rushing west for gold, and vainly seeking a compromise on slavery to avoid war, Puleo paints Sumner’s morality as a constant. We are in the courtroom as he argues against the inherent inequality of segregated schools (a century before Brown v. Board of Education), and the drawing room as Sumner persuades the sixteenth president to publicly stand for abolition. Sumner’s ideals cost him friendships and resulted in a bloody assault on the floor of the senate by a pro-slavery congressman. Puleo’s rich biographical history is a perfectly timed reminder that to survive, our union needs figures with the courage to stand for core ideals which cannot be compromised.”

Early Podcasts and Cable TV

I’ve done some early podcasts and cable TV shows for The Great Abolitionist, with others being scheduled. Here’s a couple for you to enjoy when you have the time. Booknotes + on C-Span with the legendary Brian Lamb – I had great fun on this podcast fielding questions from the man who has done this show for years and has his own inimitable style. The discussion (audio only) is about an hour. Don’t be deceived (or deterred!) by the notation that the interview is two hours – I was on Lamb’s show for my book, The Caning, several years ago, so the producers ran the podcasts back-to-back (each about an hour). Enjoy the audio interviewhere!

Author Talk with Jim Dorman on Abington (MA) Community Access and Media – The Town of Abington, which recently selected my book, The Caning, as its town-wide read, enjoys books and reading. I was thrilled to be a guest on Jim Dorman’s “Author Talk” show to discuss The Great Abolitionist for one of the first times! We recorded this show in March – before the book came out – in anticipation of my appearance at the James Library and Center for the Arts in nearby Norwell, MA on May 21. (See more information on this event below.) My thanks to Jim and Executive Director Kevin Tocci for this fine production, which you can watch here.

If You Like Audiobooks

I’m very excited that The Great Abolitionist is also available in audiobook form from virtually all major platforms, including Audible, Google Play, Kobo, B&N, etc. You may see a difference in price or format. You can listen to a small sample of the narrator, Jonathan Yen, at this link – I think he has a strong and dramatic voice! The cover image is a bit different than the print version, but I really like it!

My Blog on Sumner’s First Major Anti-Slavery Speech

As I say in my author’s note to begin this blog, I adapted this story from The Great Abolitionist because I thought it was important to highlight how Charles Sumner differed from other abolitionists. Sumner’s belief was that freedom and equality were America’s birthrights, and racists laws were a perversion of those ideals. He saw the government’s tolerance and support for the growth of slavery in the 1840s and 1850s as an ignorant misreading of the country’s founding documents, not an inevitable condition flowing from them. As one of his congressional eulogists declared, Sumner “believed in his country, in her unity, her grandeur, her ideas, and her destiny.” Let me know what you think!

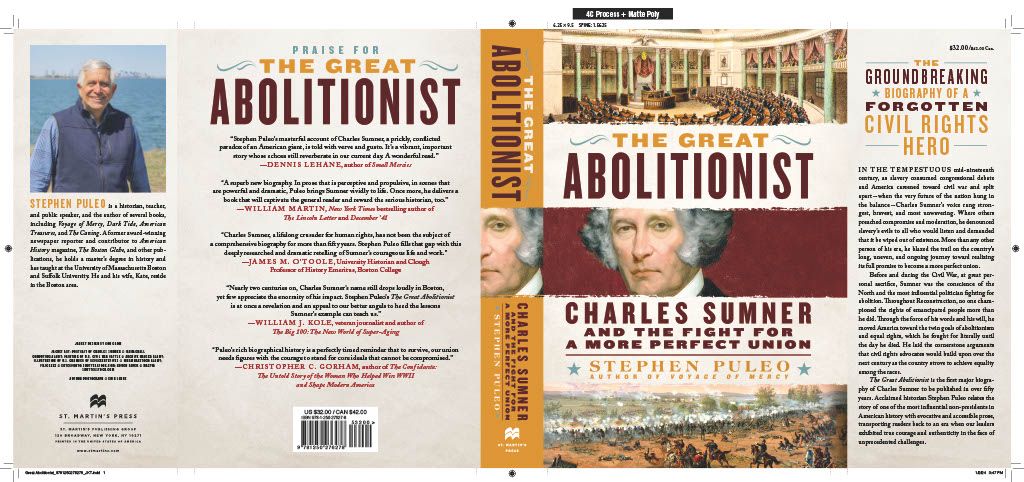

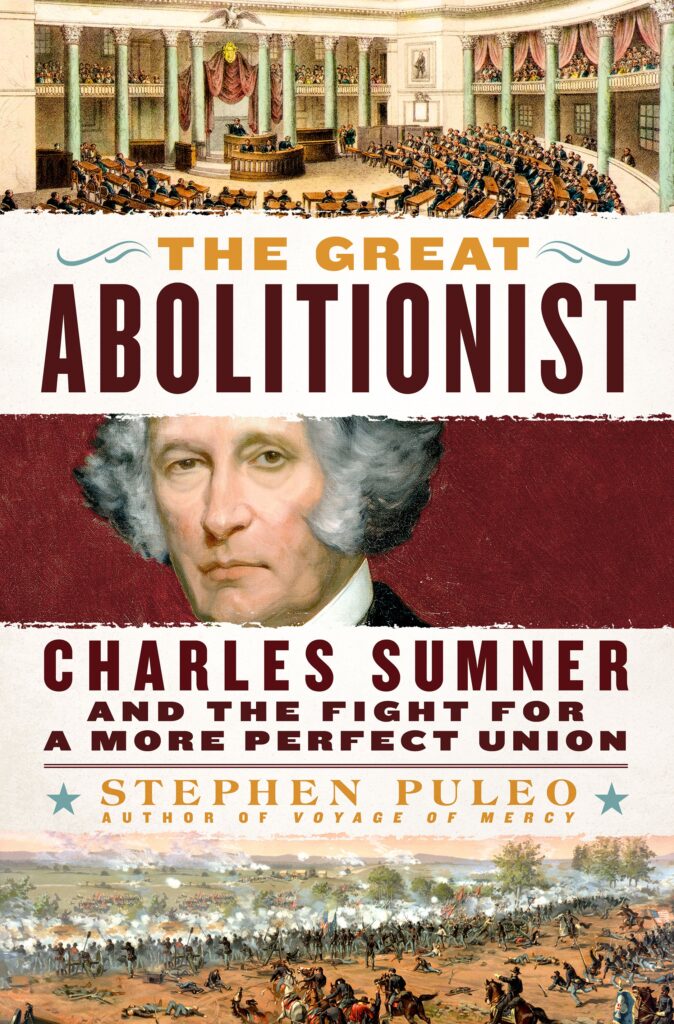

Stunning Cover Artwork for The Great Abolitionist

In case you haven’t seen it yet, the designers at St. Martin’s Press outdid themselves with the stunning cover and beautiful dust-jacket design (the back cover includes several of the blurbs that are located in the Reviews tab on The Great Abolitionist book page.) I love the battlefield and Congressional chamber images as “context-setters,” and the painting of Sumner later in life (with his penetrating eyes drawing you in) is an image even I hadn’t seen before. The whole feel of the cover is one of action and statesmanship, an appropriate combination. (For more on Sumner’s statesmanship, read my blog here.) This is my third book with St. Martin’s (American Treasures and Voyage of Mercy are the others), and in each case, I’ve been thrilled with the dramatic cover images!

THE GREAT ABOLITIONIST: Charles Sumner’s Fight for a More Perfect Union

THE GREAT ABOLITIONIST: Charles Sumner’s Fight for a More Perfect Union

The first full biography of Charles Sumner, abolitionist U.S. senator from Massachusetts, in more than a half-century!

I’m thrilled to finally announce the topic of my next book (my eighth!) – the first full biography of Charles Sumner, abolitionist U.S. senator from Massachusetts, in more than 50 years. I think you’ll truly enjoy THE GREAT ABOLITIONIST: Charles Sumner’s Fight for a More Perfect Union, which will be published by St. Martin’s Press on April 23, 2024. You can pre-order it here.

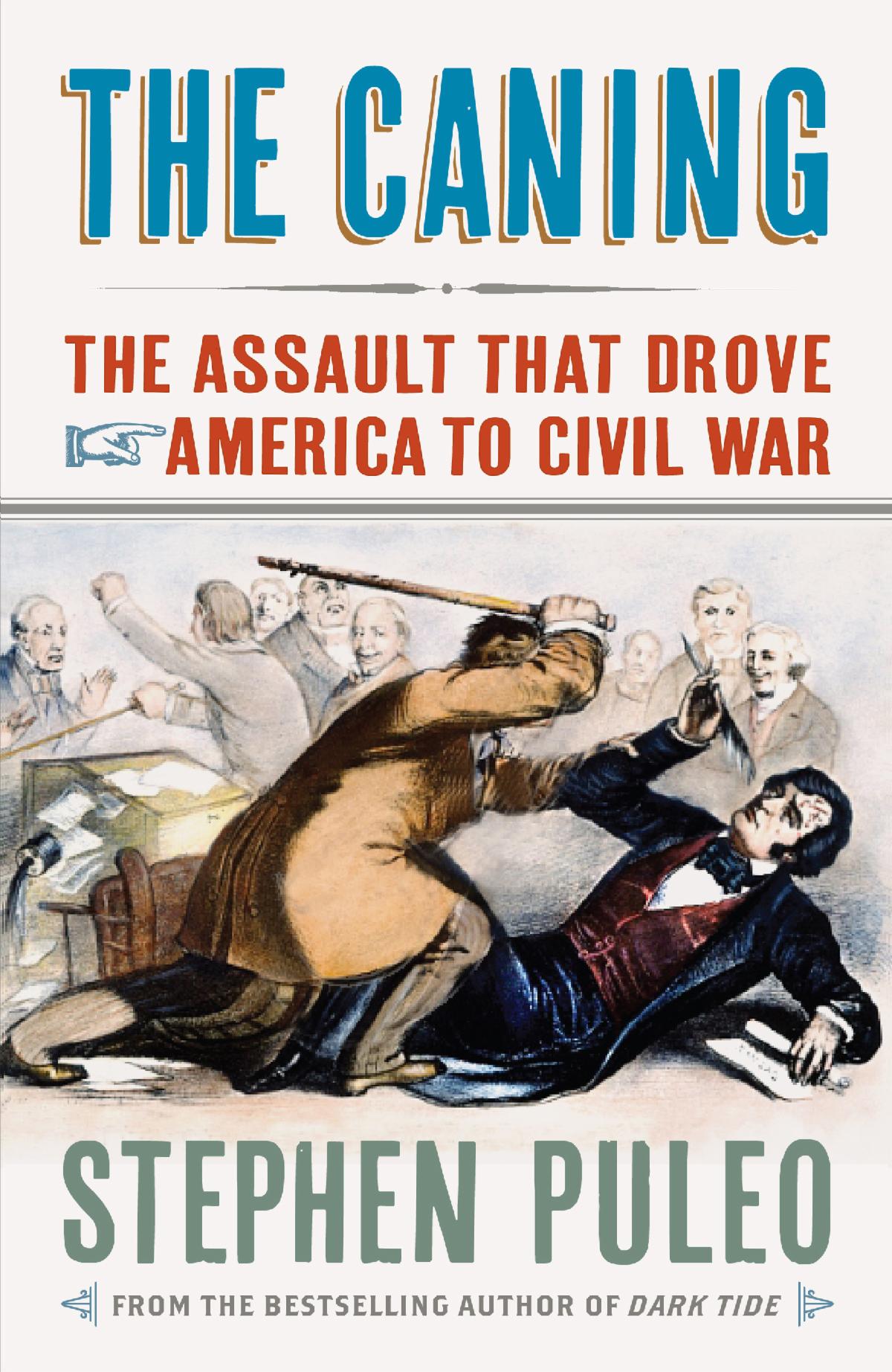

Many readers will recall that I first dealt with Sumner (briefly) in my book, A City So Grand (2010), and later more extensively in The Caning (2012), the latter of which essentially concludes with the onset of the Civil War. During the research and writing of those books, I realized what a force Sumner was throughout the 1850s and 1860s, and into the 1870s, and knew I needed to research and explore his achievements and contributions further. I also needed to learn more about this complex man.

Now, with the research and writing completed, and with The Great Abolitionist on the way to publication, I feel as if I know Sumner as well as anyone, and I feel confident in saying this: Charles Sumner is among a handful of the most influential non-Presidents in American history (and far more influential than many presidents) – standing alongside Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Susan B. Anthony.

For me, this book is a first – my first biography! And actually, I’m calling it a “biographical history,” since Sumner’s life encompassed the life of the nation during this period. He stood tall and ramrod straight at the center of events that millions of Americans would experience in his era, and then learn about and study for 175 years (and counting).

His contributions were everywhere: his unrelenting efforts to abolish slavery and fulfill the nation’s promise of civil, political, and racial equality; his expertise in foreign affairs that helped the United States avoid a potentially devastating war with England even as the country battled the Confederacy; his close working relationship with President Abraham Lincoln (Sumner was at Lincoln’s bedside the night the President was assassinated); and his influence upon virtually every major debate and issue that the country tackled in the decade prior to the Civil War, the war itself, and during Reconstruction.

The Conscience of the North

For a quarter of a century, including twenty-three consecutive years in the Senate from 1851 until his death (which encompassed a three-year absence as he recovered from his caning injuries), it was Charles Sumner – not Lincoln, not William Lloyd Garrison, not Frederick Douglass, Lydia Maria Child, or anyone else – who was the nation’s most passionate, vociferous, unrelenting, and inexhaustible anti-slavery and equal rights champion.

Before and during the Civil War, at a great personal sacrifice, he was the conscience of the North and the strongest and most influential voice in favor of abolition. Throughout Reconstruction, no one championed the rights of the emancipated Freedmen more than Charles Sumner. Through the force of his words and his will, he first moved his state, and then the nation, toward the twin goals of abolitionism – which he achieved in his lifetime – and equal rights, which eluded him and the country, but for which he fought literally until the day he died.

In so doing, he laid the cornerstone arguments that civil rights advocates would build upon over the next century as the country strove to achieve equality among the races. To Sumner, the two concepts of abolitionism and equal rights were inseparable and could not be untethered. Freedom and equality embodied the founding principles of the United States as stated in the Declaration of Independence, and in the Constitution’s guarantee of a republican form of government; only by enshrining these rights forever could the United States survive. This view was first considered radical and unworkable, dismissed as the ranting of rabble-rousers on the fringe – positions at first not held even by Lincoln and other anti-slavery Republicans.

But Sumner’s influence gradually took hold, permeated the party’s dogma, and finally became the prevalent and official view of Lincoln and the nation.

A Biographical History Since Sumner’s Story and America’s Story are Intertwined

I call The Great Abolitionist a “biographical history,” since Sumner stood tall and ramrod straight at the center of events that millions of Americans would experience in his era, and then learn about and study for the next 175 years (and counting).

These include the Fugitive Slave Law; the Kansas-Nebraska Act; the battle for the soul of Kansas that became a symbol of abolitionist and pro-slavery tensions; the founding of the Republican Party; Lincoln’s election in 1860; the secession of Southern states; as head of the Radical Republicans throughout the war; the Trent Affair in which Sumner was the primary force in averting war with England; the Emancipation Proclamation, which he repeatedly beseeched Lincoln to issue and whose language he helped shape; Lincoln’s remarkable and unexpected re-election in 1864; the President’s assassination; the crafting of Reconstruction policy; the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson; the Reconstruction amendments; as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during the administration of Ulysses S. Grant; and as the architect of a proposed sweeping civil rights bill that called for an end to all government and private sector discrimination.

As the nation literally fought for its life, Charles Sumner influenced, altered, and often defined America’s course – in the moment and for the future. In the face of repeated insults, ridicule, personal setbacks, and a devastating physical attack, Charles Sumner’s voice and his ideas moved a nation, slowly, even grudgingly at first, but eventually with a surety that accompanies righteousness.

Sumner Believed in America

For Charles Sumner, freedom and equality were America’s national birthright, and slavery and racist laws were a perversion of those ideals. He saw the government’s tolerance and support for the growth of slavery as an ignorant misreading of the country’s founding documents, not an inevitable condition flowing from them.

In the end, Charles Sumner truly believed in America. He believed in it as he held up a mirror to its flaws and challenged the country to live up to its ideals. He believed in it as he ferociously battled slavery and inequality. He believed in it as he endured and recovered from a vicious beating for speaking his mind. As one Congressional eulogist declared, Sumner “believed in his country, in her unity, her grandeur, her ideas, and her destiny.”

Dour and disconsolate as he often appeared, he was an idealist at heart. He told all who would listen that his often lonely fight to create a more perfect union was a burden well worth shouldering – that the fulfilled promise of America could literally change the world.

The Great Abolitionist Is Sweeping In Scope and I’m Confident You’ll Enjoy the Story!

You’ll find that The Great Abolitionist is sweeping in its scope, but rather than focusing on Sumner’s every movement and utterance between childhood and death, this “biographical history” traces the arc of his antislavery and equal rights leadership as he stood at the center of the storm that swept across the nation during the 1850s and 1860s.

From the moment Charles Sumner stepped onto the public stage, he made his fight America’s fight. I’ve tried to tell the story — Sumner’s story, the nation’s story — with the same fast-paced narrative style and an exciting story arc that you’ve become accustomed to in my previous books.

If you’ve enjoyed my other work, I believe you will enjoy The Great Abolitionist, too!

I’ll have more to say about The Great Abolitionist in the future, so please stay tuned! Meanwhile, check out my blog for a few more insights about Charles Sumner’s courage and authenticity. And be sure to schedule some reading time for early next year!

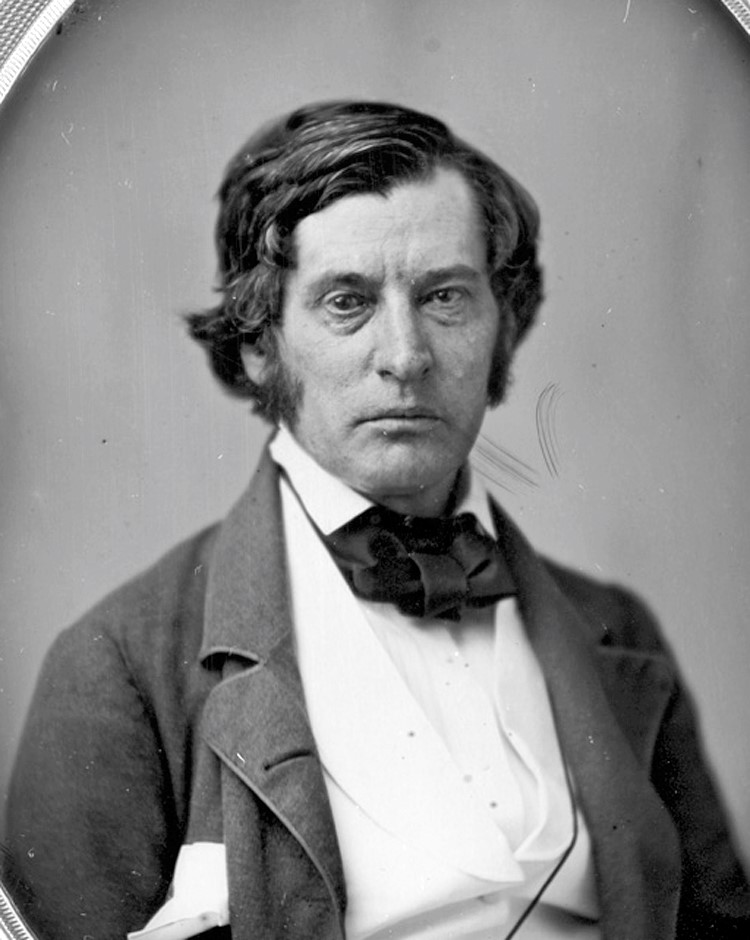

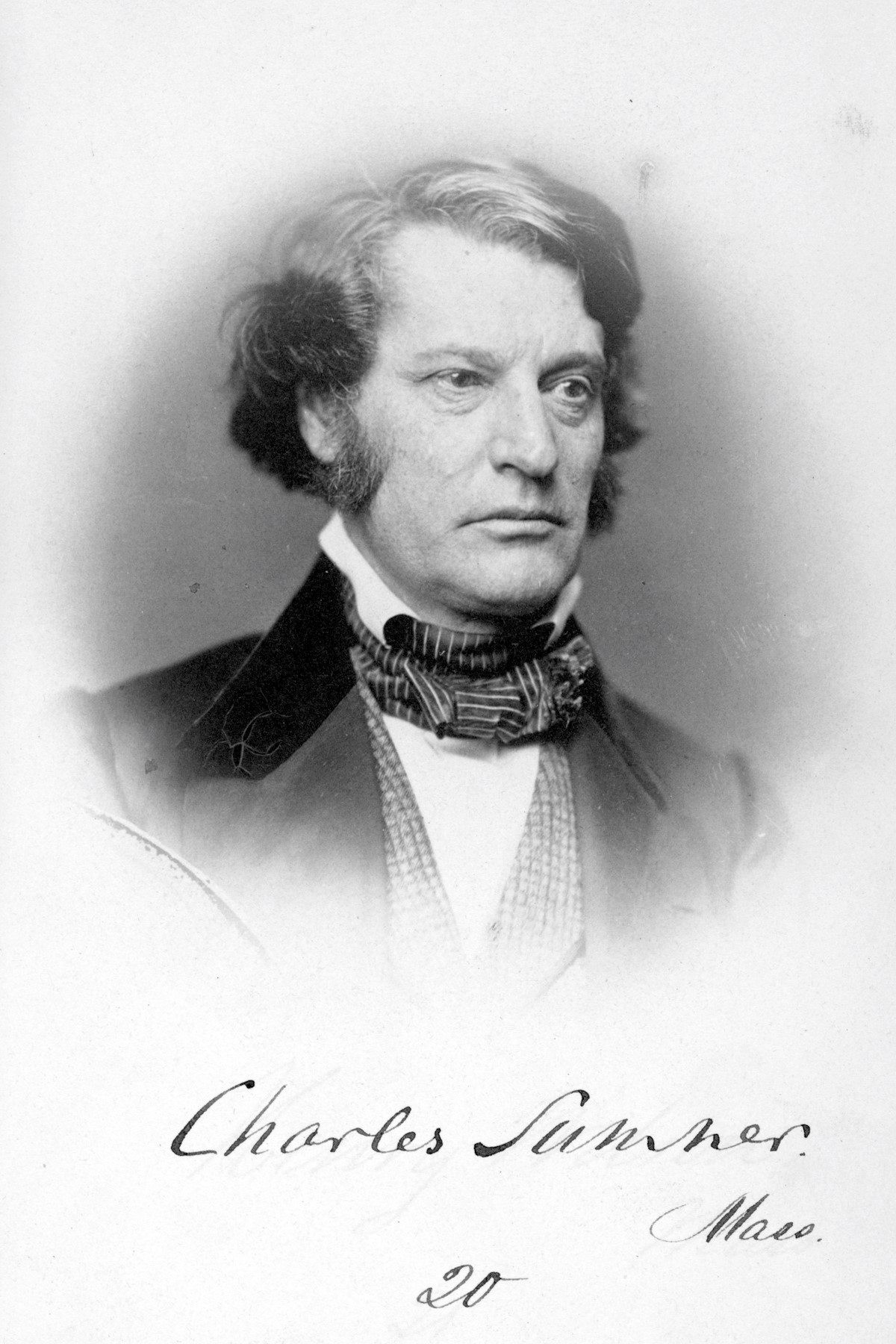

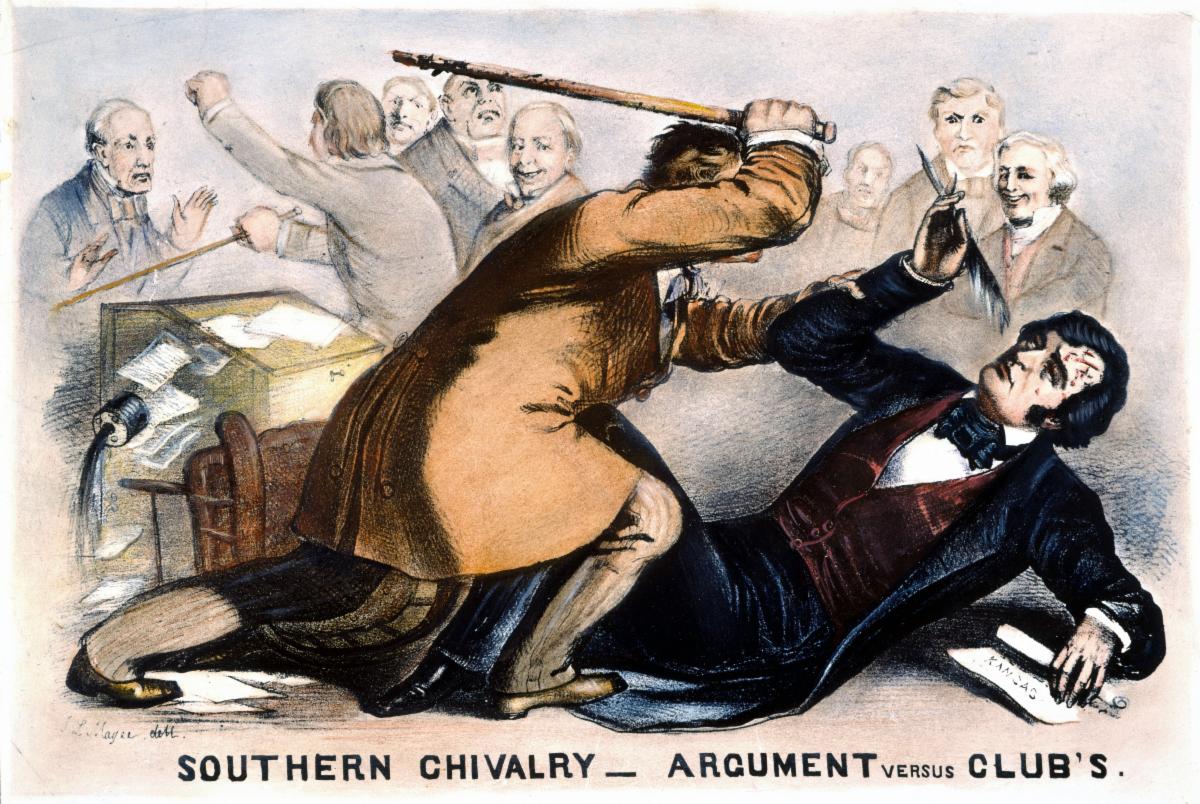

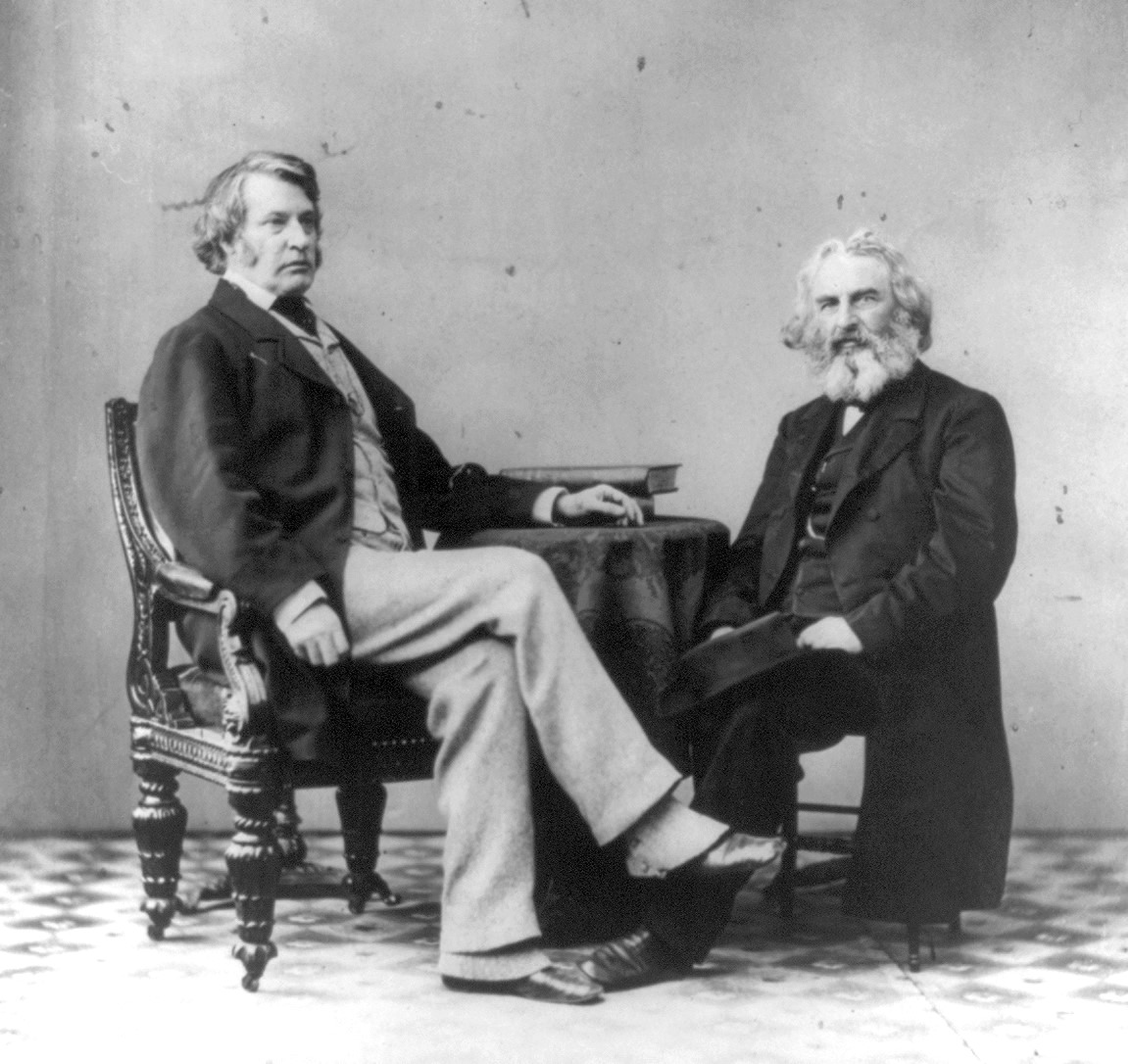

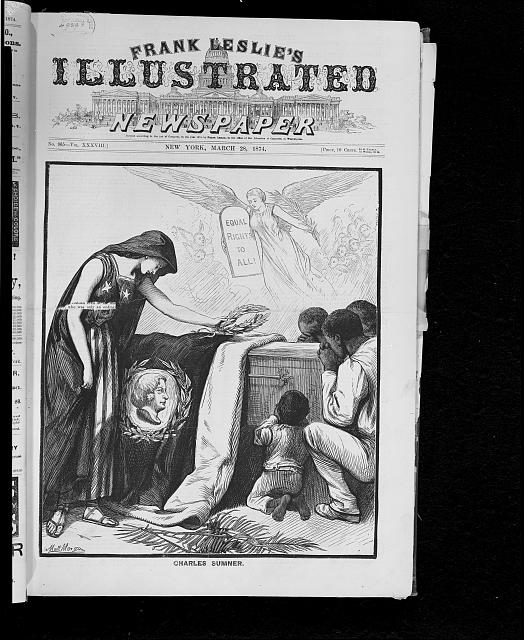

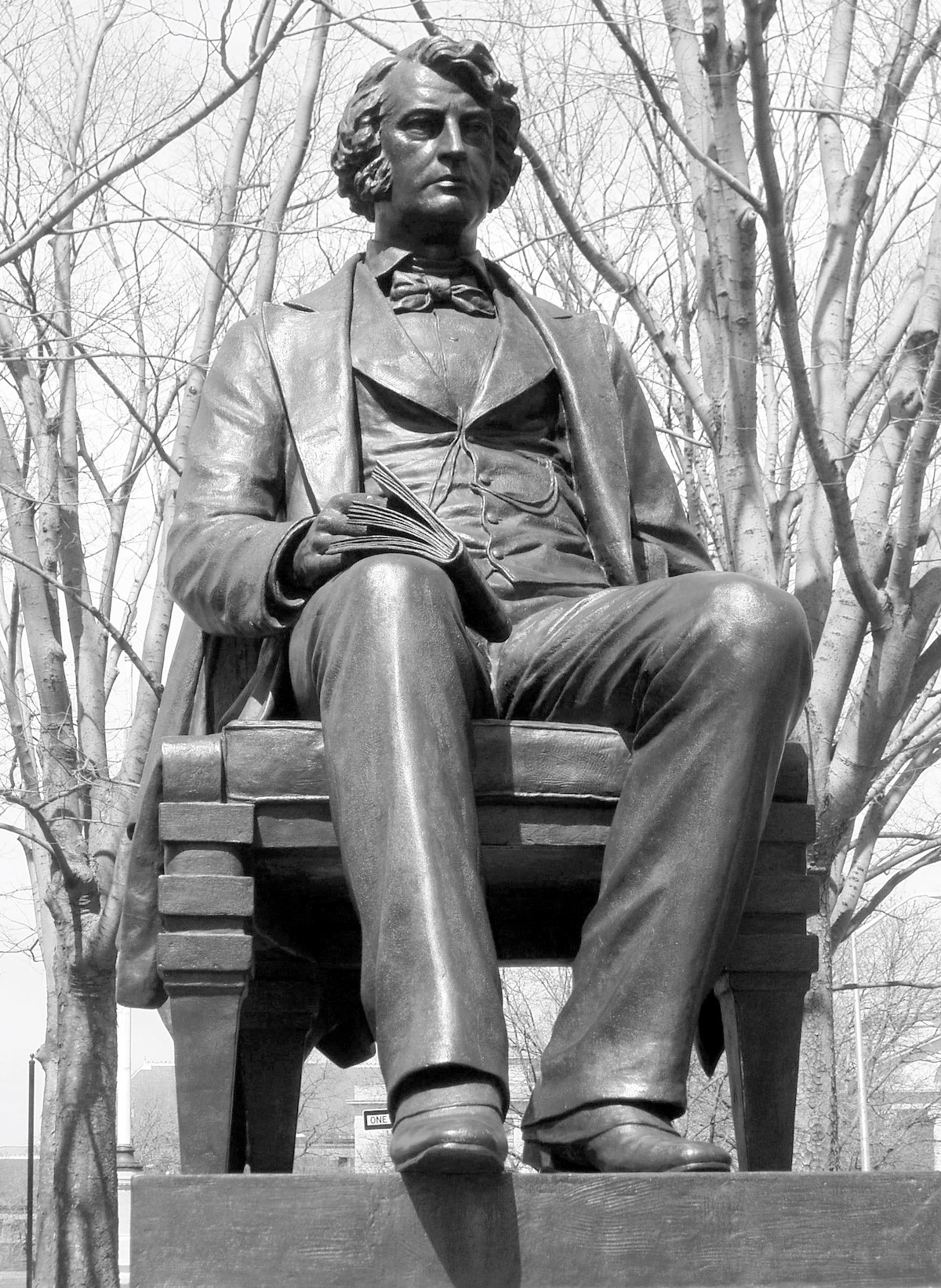

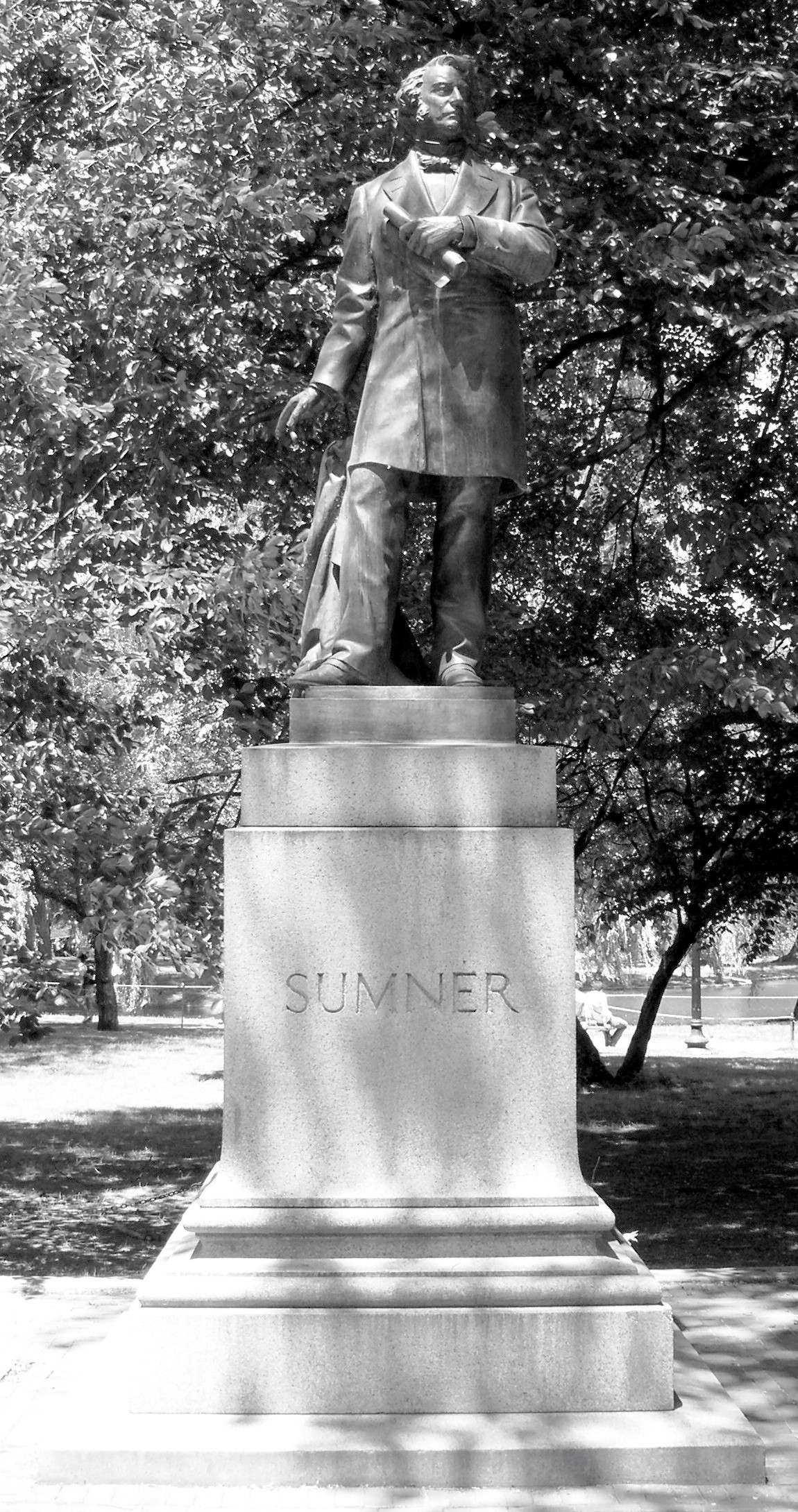

Photos show Charles Sumner in 1855 and 1859; a painting of his caning attack by South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks; Sumner later in life with his dear friend, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow; Sumner’s deathbed scene, where he is surrounded by friends, including former slave Frederick Douglass; a magazine cover announcing his death in which former slaves are depicted paying him tribute; and his statues at Harvard and on Boston’s Public Garden.

“The groundbreaking biography of a forgotten civil rights hero”

As I mentioned, I couldn’t be happier with the description of The Great Abolitionist from MacMillan Publishers, the parent company of my publisher, St. Martin’s Press. (Check out the full notice here.)

At this point in the publication process, I am reviewing final page proofs (and they look great!), and we are awaiting “back-cover” blurbs from other authors and historians who kindly agreed to offer advance comments on the book. In upcoming newsletters, I’ll continue to update you on progress as the exciting publication date approaches!

Also, I already have several speaking events in the works for The Great Abolitionist for next May and June – some are finalized; others are in process. You can always check out my schedule on my website’s “Events” page and I’ll have additional updates on these appearances as time goes on. If you’re an organization that would like to schedule an event, I’d urge you to contact me soon at spuleo@aol.com.

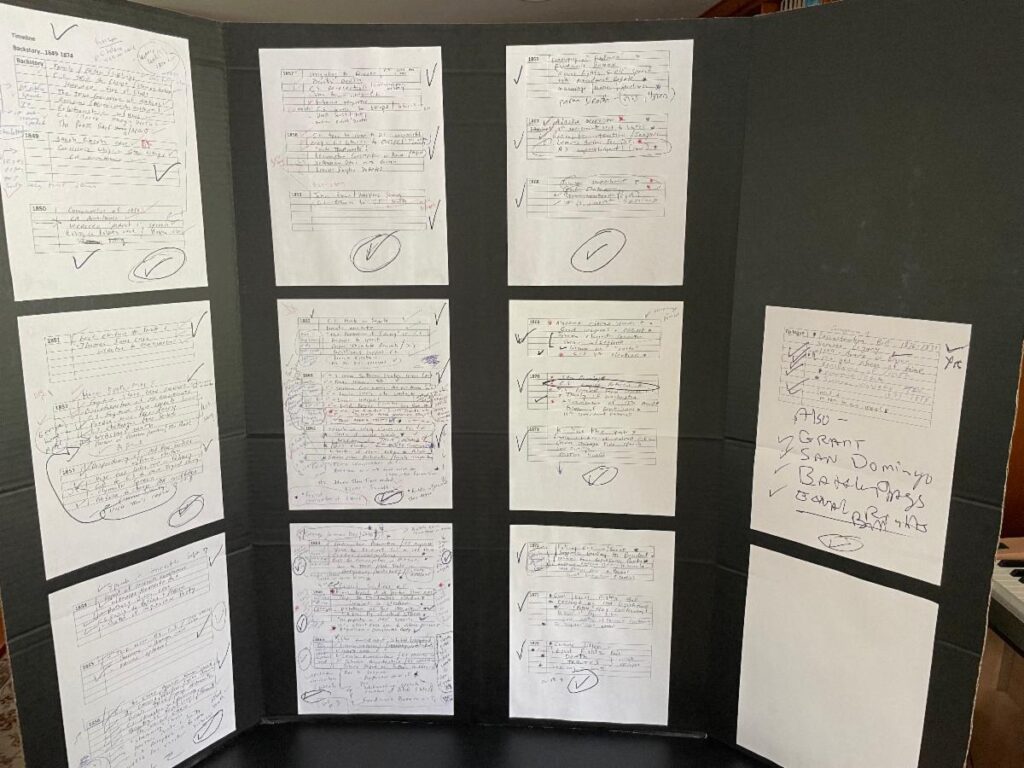

And one other thing related to the upcoming book… I’m asked often about how I begin and organize research. With the Sumner biography, I realized early on that, because the material on him was so voluminous, I definitely needed a large and easy-to-refer-to, year-by-year timeline of events, and potential scenes and chapters. I do a version of this for all of my books, but the Sumner bio required a longer timeline because of the nearly 25 years that he influenced (and was influenced by) the major events occurring in the United States.

So, I’ve included a photo of my “big board” here that enabled me to stay anchored during the research and writing of The Great Abolitionist. Zoom in if you’d like to check out my early research thoughts (and apologies if you have a tough time reading my writing — sometimes I’m scribbling fast!). This is basically how the process starts for me!

The Caning of Charles Sumner (and my book, The Caning) in the news – and beyond…

I’m pleased to have been asked to share my expertise and take part in several activities, interviews, and (upcoming) events related to my book The Caning, and to the caning of Charles Sumner (this dramatic episode will also be included in The Great Abolitionist). Here’s a sampling of five collaborations:

Boise State Public Radio podcast

With The Great Abolitionist coming out in April, the timing seemed right to participate in a podcast being developed by two Boise State University professors on the caning of the Massachusetts senator that occurred in May 1856 (and which I wrote about in my book, The Caning – 2012). BSU professors Charlie Hunt and Jaclyn Kettler are developing a podcast for the Boise NPR station called “Scandalized,” which will investigate different political scandals throughout history. It will begin airing next spring in Boise and – the organizers hope and plan – will be picked up by other NPR affiliates across the country. The caning of Charles Sumner will be the subject of the third episode of “Scandalized.” Charlie Hunt and I conducted an extensive interview, which will be featured in the narrative style program. As we get closer, I’ll provide you with more information on the broadcast, accompanying links, etc.

The Bill of Rights Institute Features My Lesson Plan on The Caning

I’m excited that the Virginia-based Bill of Rights Institute features my summary and student lesson plan on Charles Sumner and Preston Brooks based on my 2012 book, The Caning: The Assault the Drove America to Civil War. Brooks, a congressman from South Carolina, was Sumner’s assailant in the highly publicized event that The Caning analyzes. The lesson highlighted by the Bill of Rights Institute includes the outline of the event, a summary of the time period, review questions, AP (Advanced Placement) test practice questions, and numerous primary and secondary sources. Of course, the attack on Sumner will be included as part of The Great Abolitionist, but my new book will also cover the full breadth of Sumner’s contributions during the run-up to the Civil War, the war itself, and Reconstruction. If you or a student you know is interested in this dramatic era of American history, or specifically on this astonishing event that put the country irrevocably on the path to Civil War, I urge you to check out the lesson on the Bill of Rights Institute website and let me know what you think!

Recent U.S. Senate Dust-up Prompts Interview with Boston.com/Boston Globe Reporter

The recent U.S Senate dust-up between Oklahoma Senator Markwayne Mullin and Teamster President Sean O’Brien prompted Boston Globe/Boston.com reporter Molly Farrar to reach out and ask me if we could draw any comparisons with the caning of Charles Sumner in May 1856. “No,” I replied, despite some in the media who attempted to do so. The recent skirmish (barely an event) was over quickly, involved words only, and I think will be little remembered. The caning of Charles Sumner, on the other hand, was one of the most shocking and provocative events in American history. It transformed the whole debate over slavery from an intellectual, religious, moral discussion to a visceral one, helped elect Abraham Lincoln as President in 1860, and put North and South on an inexorable road to Civil War. Check out the interview here

Abington, MA Selects The Caning as its community-wide read for 2024!

I’m thrilled that the Abington (MA) Public Library has selected The Caning as its “Abington Reads” choice for 2024! If you want to mark your calendars early, I’ll be appearing at the Abington Public Library (600 Gliniewicz Way) on March 14, 2024 at 7:00 p.m. to discuss the book. You can find out more here. Just scroll down a bit and get the full info on this event!

A gem of a World War II museum in New Hampshire!

If you live in or are visiting the New England area, and you’re interested in World War II (as I am), I strongly suggest you visit the fabulous Wright Museum of World War II in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire!

I had long heard about the museum, but had never visited until this summer – and was I impressed! The museum contains an extensive collection of artifacts, videos, military vehicles, memorabilia, and primary source documents from 1939-1945. It focuses on both the war overseas and the American home front and preserves the legacy of the Greatest Generation.

The creation of its visionary founder, the late David Wright, the museum opened in 1994 and has been going strong since. It’s a 30,000-square-foot museum with more than 14,000 items in the collection. And that doesn’t include its archival collection, which I didn’t get a chance to explore on this trip – but certainly plan to in the future! According to archival curator Justin Gamache, the archives contain documents, such as personal letters, enlistment records, diaries, and pamphlets; thousands of photographs; and “3D” artifacts such as uniforms and hardware.

Learn more here and please make a point to visit this gem of a museum in New Hampshire’s Lakes Region!

The Quest for 351 — Walking and Hiking Massachusetts Cities and Towns

On a personal note, over the past few years, Kate and I have been visiting communities throughout Massachusetts on a quest to walk or hike in all 351 cities and towns! Happy to say we have reached 120 communities, a little more than a third of the way through. We love the combination of history and nature. (It’s the more local version of our “road trips” that I periodically chronicle on my Highlights page.) Most recently, we visited the towns of Marion and Mattapoisett on the south coast, with an additional walk in adjacent Rochester. Here’s Kate at the Osprey Marsh boardwalk in Marion and at the beautiful Munn Preserve harbor in Mattapoisett.

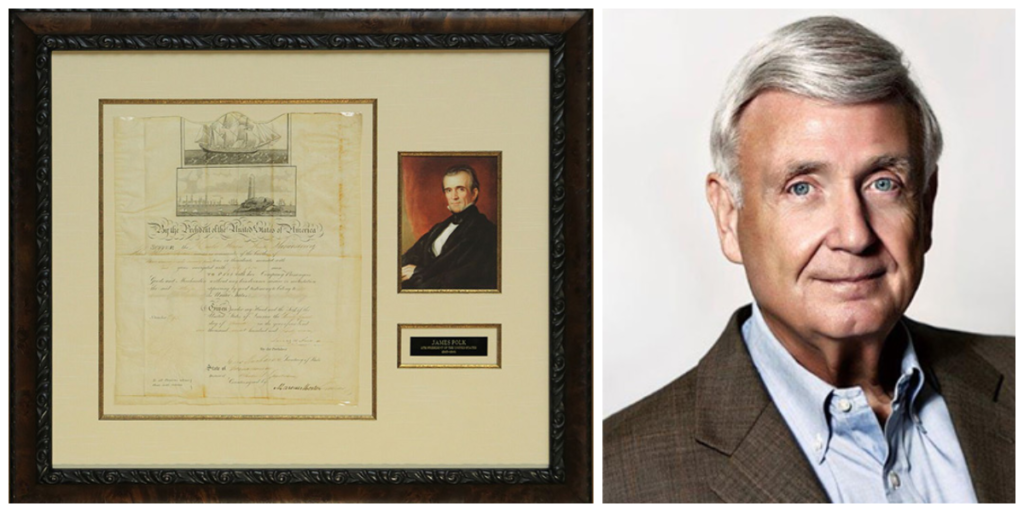

A Generous Voyage of Mercy Reader shared the Presidential-issued “Passport” for the USS Jamestown

One of my favorite enjoyments of this author life is the opportunity to meet and learn from so many readers. Enter Richard “Jerry” Dodson (shown below), a maritime attorney who co-founded the Baton Rouge, Louisiana-based Dodson & Hooks law firm, one of the world’s leading maritime law firms. A graduate of Louisiana State University (LSU) Law School, Jerry is an advisor and frequent presenter at LSU’s annual Rubin Maritime Law Seminar.

Luckily for me, for the past forty years, Jerry has also been a passionate collector of maritime art and antiques. Through the years he has collected numerous “ships passports” and donated his collection to LSU Law School (The Richard J Dodson Maritime Art Collection). At one point, J. Revell Carr, former president and director of Mystic Seaport’s museum of The America and The Sea Society, spent a week in Baton Rouge, and discovered that Jerry possessed the passport of the USS Jamestown (the document shown below), the first U.S. ship to transport food to Ireland during the 1847 potato famine, and featured in my book: Voyage of Mercy: The USS Jamestown, the Irish Famine, and the Remarkable Story of America’s First Humanitarian Mission. Jerry, who said he enjoyed Voyage “immensely,” was kind enough to share this news with me — I had no idea the passport even existed!

Officially, the document is called a “Mediterranean Passport,” and was created after the United States concluded a treaty with Algiers in 1795. America was one of several nations paying tribute to the Barbary states in exchange for the ability to sail and conduct business in the Mediterranean area without interference from pirates. This treaty provided American-owned vessels with a “passport” that would be recognized by Algeria and other Barbary states, which allowed the ships safe passage. In general, virtually any American vessel — whether they were venturing into the Mediterranean area or not — was required to carry the passport. Hence, the Jamestown’s passport issued by President James K. Polk.

My thanks to Jerry Dodson for sharing this information and this rich piece of history!

Let me know if you need a “dining room” inscribed book

If you’re unable to attend one of my appearances, a “Puleo dining room signing” might be for you.

Let me know if you’d like an inscribed or autographed book for a friend or loved one (or as a gift to yourself!). Email me at spuleo@aol.com to find out how to get your copy.

I’ve done this many times for readers and it has worked out well. To fulfill your request in time, though, please contact me as soon as possible. Thanks, as always, for your support!

Molasses Flood Artwork on Display at the Boston Public Library

And now for something really cool and unique, and of special interest if you’re a fan of my book, Dark Tide!

The Boston Public Library (BPL) has commissioned a composite tile mosaic from artist Duke Riley entitled Enchafed Flood, which depicts the Great Boston Molasses Flood. To get a sense of scale, the tile mosaic is 41 3/8 x 81 1/2 inches.

Riley, an artist of international fame who has been the subject of front-page articles in the New York Times, draws, sculpts, tattoos, engraves and paints subjects that blend history, fact, fiction, and myth. He currently has a major exhibition on view at the Brooklyn Museum: Death to the Living, Long Live Trash.

The BPL’s description of Enchafed Flood reads in part: “Riley’s work depicts the cataclysm and near-biblical tumult of this incident in vast tilework that recalls the color and lines of his trademark ink-on-paper drawings.”

Duke was kind enough to give me permission to use the image of Enchafed Flood. He said he has read Dark Tide and added: “It’s great, and I reference it all the time.”

Enchafed Flood is the first work acquired by the Arts Department at the BPL for permanent view in the historic McKim Building since 1919! It’s on view in the first-floor elevator lobby at the Central Library in Copley Square.

A great visit with Canadian readers!

Meet Sean Polreis and Andrea Book, residents of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, who invited me to lunch at L’Osteria Italian restaurant (one of my faves!) in the North End during their recent trip to Boston.

Meet Sean Polreis and Andrea Book, residents of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, who invited me to lunch at L’Osteria Italian restaurant (one of my faves!) in the North End during their recent trip to Boston.

Sean and Andrea love the city of Boston and are also loyal Puleo readers, for which I’m very grateful (their interest in the city first led them to my book, A City So Grand). So, I was honored when they reached out and asked if we could get together! Boston is basically their second home; they enjoy the city’s theater, food, culture, history, and “walkability.” And they are HUGE Boston sports fans.

Those of you who have followed me here and elsewhere know how much I enjoy connecting with readers. My thanks to Sean and Andrea for giving me another opportunity to do so!

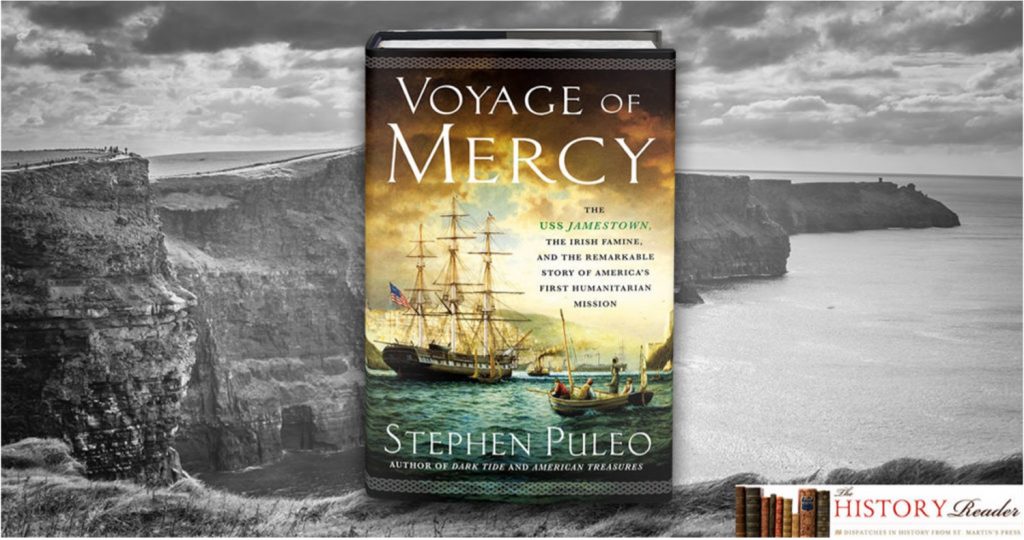

Excerpts from Voyage of Mercy

I’ve included two excerpts from Voyage of Mercy here that I think you’ll enjoy. The first, a longer excerpt, was published in “The History Reader,” the St. Martins Press website devoted to history topics. It focuses on Father Theobald Mathew, who worked hard in Ireland on behalf of victims. The second short excerpt describes the beginning of the USS Jamestown voyage to Ireland under the command of Captain Robert Bennet Forbes.

If you prefer hearing an excerpt, you can listen to a five-minute sample of award-wining Sean Patrick Hopkins narrating the story here, and also order your own audio version of Voyage of Mercy from Audible.

Voyage of Mercy: “The Distress is Universal”

Ireland, 1846. Father Theobald Mathew implores assistant secretary at the British Treasury, Charles Trevelyan, to provide aid to Ireland as the potato blight ruins crops across the country. Read on for an excerpt from Voyage of Mercy. December 16, 1846, city of Cork, County Cork

When night finally came, a bone-weary Father Theobald Mathew dipped the nib of his pen into the ink and scratched the full measure of his despondency onto the page.

He aimed for precision with his writing, but he also needed to modulate his description of a truly appalling situation. Bold, direct words were necessary, but overly inflammatory language would raise skeptical eyebrows in London, damage his credibility, and, most importantly, put thousands of additional lives at risk. This was his fifth letter since August to Charles Trevelyan, assistant secretary at the British Treasury responsible for famine relief efforts, each more desperate than the last. Now, just days before Christmas, Mathew wrote with renewed urgency, hoping that his reputation for directness and honesty, and as a champion for the poor, would convince Trevelyan of his veracity.

“I am grieved to be obliged to tell you that the distress is universal,” he lamented at the outset of his letter. “Men, women, and children are gradually wasting away.” It was not the first time Father Mathew had underlined passages to emphasize the urgency of his message, and it would not be the last. Reviewing his opening words, he debated whether he had succumbed to the very temptation he sought to avoid—the use of sensational rhetoric. In the end he decided to let the letter stand: he knew of no more accurate way to describe the heartbreak he witnessed each day. These imperiled citizens were not anonymous “famine victims” but people he knew and loved—neighbors, parishioners, followers, friends.

He would speak for them.

In some ways, these were the most frustrating and dispiriting hours for the fifty-six-year-old priest, sitting quietly at his desk, fighting exhaustion, his eyes straining by his lantern’s pallid light in the otherwise dark parlor, his desktop covered with ink-stained pages and the floor beneath him strewn with correspondence. Daytime hours were a blur, physically draining and mentally dispiriting—Mathew had just returned from several weeks’ work in different parts of Ireland, assessing the potato blight, organizing relief efforts, comforting the sick, ladling soup to the hungry, kneeling at their deathbeds and praying for their souls, presiding over their burials. Upon his return to Cork he discovered that his city and county were among the hardest hit by the famine; again his daytime hours were consumed with tending to those burning with fever or filling their stomachs with “cabbage leaves and turnip tops . . . to appease the cravings of hunger.” The night offered time to reflect, to be sure, but these were unwelcome and damnable hours, for it was while he sat alone in the darkness that the full tragedy of the widespread hunger, coupled with the futile sorrow that he could do little or nothing to stop it, pressed upon him like a great stone.

* * * * *

The destruction of the potato crop had occurred—or, rather, revealed itself—almost overnight. Mathew himself was one of the first to observe and report on the disaster. In late July, he was traveling from Cork to Dublin and saw fields of potato plants blooming “in all the luxuriance of an abundant harvest,” a sight that heartened him after widespread potato-crop failure a year earlier had resulted in severe food shortages, but not full-scale famine. But six days later, August 3, during his return trip to Cork, Mathew’s spirit was shattered when he “beheld, with sorrow, one wide waste of putrefying vegetation.” The blight, caused by a fungus that thrived and multiplied in Ireland’s damp climate, had reproduced with lightning speed. In many places along the road, “the wretched people were seated on the fences of their decaying gardens, wringing their hands and wailing bitterly against the destruction that had left them foodless.”

Four days later Mathew expressed the worst in a letter to Trevelyan: “The food of a whole nation has perished.” The Times of London concurred: “From the Giants Causeway to Cape Clear, from Limerick to Dublin, not a green field is to be seen.” Indeed, on September 2, the Times declared that “total annihilation” had befallen the Irish potato crop. At this point, more than one-third of the entire Irish population depended exclusively on the potato for food and as a cash crop, but among poor tenant farmers, the proportion was even higher; a strong potato crop was their only hope for sustenance, for nourishment, for life itself.

Even pre-famine, survival had been precarious in Ireland, as tenant farmers and peasants scratched out a living raising and selling potatoes, or perhaps traded a pig or a cow for other goods. Food shortages were a near-constant peril, and temporary migration was a lifeline for many Irish families engaged in agricultural work, particularly those from western counties; seasonal trips to the grain-growing areas of the eastern counties, and to England, were commonplace. In the first half of the nineteenth century, seasonal migrants, often accompanied by their livestock, walked along Ireland’s dusty roadways in search of work and food.

Now such searches proved more and more futile.

Since Mathew’s August letter, the downward spiral had progressed with alarming speed. Now, he wrote to Trevelyan, more than 5,000 “half-starved wretched beings from the country” were begging on the streets of Cork city; “when utterly exhausted, they crawl to the work- houses to die.” He estimated that more than a hundred people a week were dying in his parish. And because of the frightful calamity that had swept the countryside, where food was all but nonexistent, thousands of peasants straggled into the city in search of something to eat, further straining scarce resources. Ten to twelve people a day died from starvation in the village of Crookhaven, where the community organized a collection to purchase a public bier upon which to place the bodies of those whose families could not afford coffins. Mathew was filled with dread, not only for the current state of affairs, but for the unknown depth of the abyss that lurked ahead.

“This country is in an awful position,” he stressed to Trevelyan, “and no one can tell what the result will be.”

The USS Jamestown en route to Ireland – March 1847

Sheets of cold rain lashed the decks of the USS Jamestown and gale-force winds battered the three-masted American sloop of war through the swells of the North Atlantic. Captain Robert Bennet Forbes barked orders as his energetic but inexperienced crew scrambled to haul up the mainsail, a daunting task on this moonless night of raging seas, on April 2, 1847. Weak light leaked from deck lanterns, but beyond the ship’s raised prow and forward riggings, the darkness was total — “black as Erebus,” as Forbes described it in the captain’s log, referring to the mythological netherworld that serves as the passageway to Hades.

For the sixth straight day since leaving the Charlestown Navy Yard, the ship and its crew were pounded by miserable weather as they fought their way toward Ireland. Snow, sleet, hail, and cold rendered all ropes “stiff as crowbars . . . and the men also,” and wind and waves left the Jamestown, despite her solid oak frame, “bounding like an antelope” and unable to carry as much sail as Forbes wished. Dense wet fog rendered visibility to near zero. Snow slickened the ship’s decks, crew members lurched with seasickness, ice floes hampered passage, and worst of all, the Jamestown leaked badly, at times taking on as much as ten inches of water an hour. Most of the water poured through the rudder case in the wardroom when the sea rose aft or the ship settled. Crew members were forced to pump often and, finally, bore holes in the wardroom deck to allow water to run off into the hold.

As midnight approached, the wind howled and every rope froze “as hard and stiff as January,” but Forbes, a Bostonian who in his forty-two years had savored much joy and endured deep sorrow, remained unflappable in the captain’s chair, determined to reach his destination ahead of schedule, and resolute in the righteousness of his mission.