One message came through repeatedly while I was researching and writing THE GREAT ABOLITIONIST: Charles Sumner’s Fight for a More Perfect Union: Americans today who crave, above all else, courage and authenticity in their leaders would have enjoyed watching Charles Sumner work in the mid-nineteenth century.

Where others preached compromise and moderation, Sumner never wavered in denouncing slavery’s evils to all who would listen and demanding that it be wiped out of existence. Where others muttered cautious, even insipid platitudes, his voice was clear and strong, and unambiguous on the issues of freedom and equality. Where others wilted under the onslaught of political attack, he stood strong and fearless, a bulwark against the slings and piercing arrows of those who targeted him — Southern slaveholders for sure, but also many Northerners who placed their economic interests ahead of their moral outrage.

Sumner was beholden to no one, sought no ill-gotten gains, was unbribable and unbuyable, and had little interest in even currying favor to advance his own political fortunes. And he never, ever pandered.

Hard to believe he was a politician!

Charles Sumner was the biggest, boldest, most controversial, and most influential national voice of America’s most turbulent two decades; the 1850s and 1860s. No one else came close. As great events played out across the land during the country’s most stormy and divisive period, Sumner seized the national narrative, refused to let go, and repeatedly held a mirror up to the country’s aspirations and ideals. He inspired those who agreed with him, swayed fence-sitters, and eventually, converted millions of naysayers to his point of view.

It was Sumner who first used the phrase “equality before the law” in the United States, who first argued that “separate but equal” violated the precepts of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and who infused the concept of “equal protection” for all into the language of the Fourteenth Amendment.

His oratory was his gift if occasionally his undoing. He never backed down, never tempered his remarks, never prevaricated. He understood the evocativeness of words and the power of sweeping themes. Merely uttering the words “United States Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts” was enough to stop both his allies and his enemies in their tracks. Supporters trumpeted his courage, his resilience, and his moral certitude. Detractors detested his insolence, his arrogance, his seeming lack of empathy for others, and his contempt for those who disagreed with him.

But without question, when Charles Sumner spoke, everyone listened.

Like Winston Churchill during World War II and Martin Luther King, Jr. during the Civil Rights era, Sumner relied most heavily on the uncompromising clarity of his ideas, his relentless honesty, and his fearless steadfastness as his most effective attributes as he sought to move the heart and mind of a country embroiled in crisis. Like Churchill and King, too, he employed rhetoric befitting big moments, and like both twentieth-century leaders, he shaped – and was shaped by – grand causes and occurrences.

Sumner knew instinctively what was at stake and how to convey it in his oratory and his writing. No single individual did more to influence the anti-slavery movement on a national scale. No single person was more responsible for founding and fueling the growth of the anti-slavery Republican Party and influencing Abraham Lincoln’s ideas. No single lawmaker advocated for such broad and sweeping equal rights, and made the discussion of such rights a reasonable and respectable option for so many Congressional colleagues during political discourse. No single person insisted so fervently and so early that the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution guaranteed both freedom and equality (Lincoln would eventually adopt and promulgate this view with brilliance).

His positions cost him dearly. Southerners despised Sumner, sometimes feared him, and celebrated gleefully when he was beaten unconscious in the Senate Chamber. Northerners blanched at his abolitionist calls at first, resisted his later demands for equal rights as detrimental to the nation’s attempts to heal, and often found his chafing personality off-putting.

But eventually, they came to respect him and his positions, and near the end of his life, they elevated Sumner to revered elder-statesman status.

More than any other person of his era, perhaps of any era, Charles Sumner’s political courage and moral authenticity blazed the trail on the nation’s long, uneven, and ongoing journey toward realizing its full promise – its ever-striving quest to become a more perfect union.

###

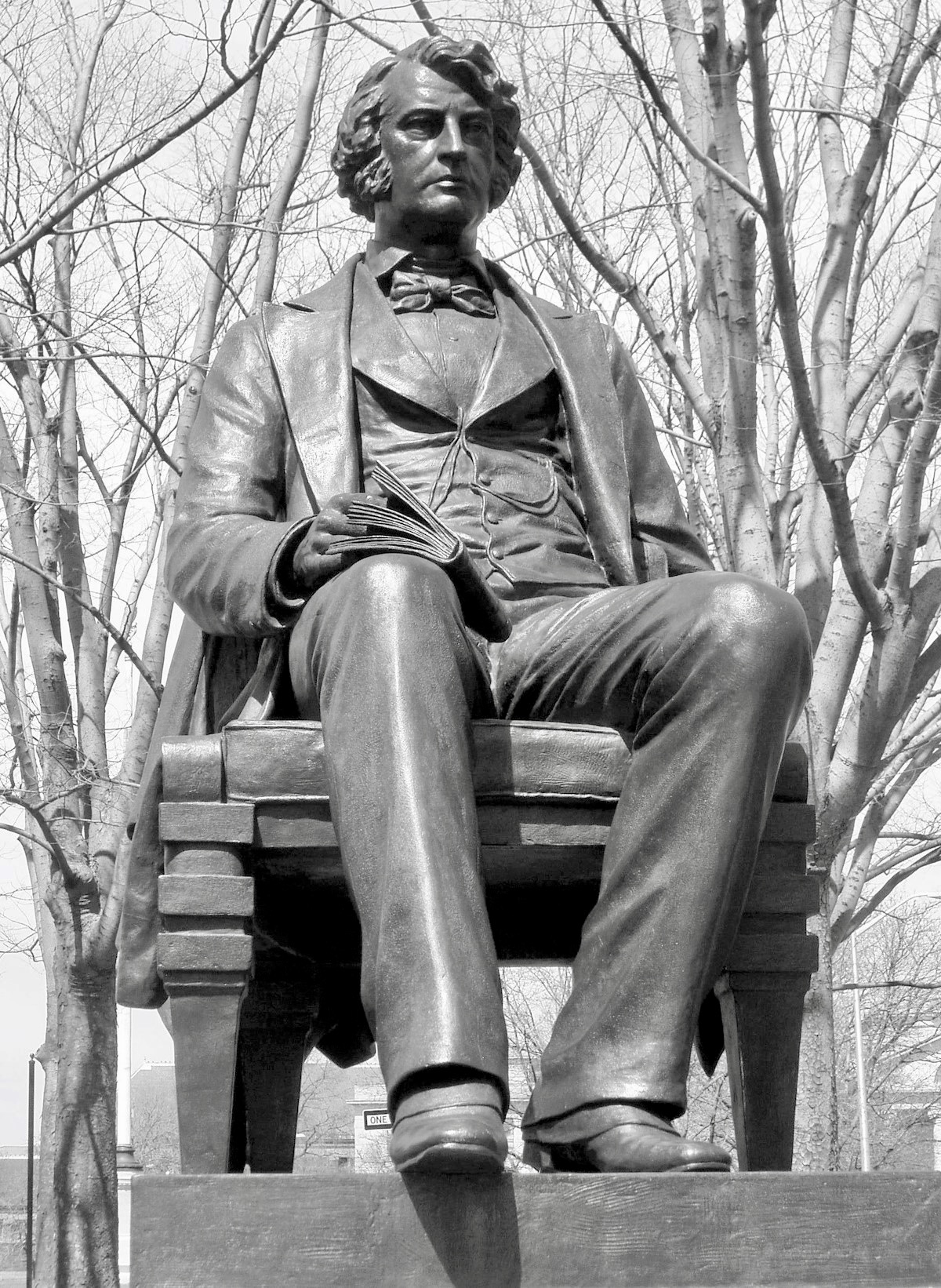

Charles Sumner’s statue at Harvard College, his alma mater

Charles Sumner’s statue at Harvard College, his alma mater